Geographical diversification driving wealth to Asian region

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It might seem logical that war in Ukraine, inflation, rising interest rates and market turmoil would make the outlook for stockpiling wealth just a little uncertain.

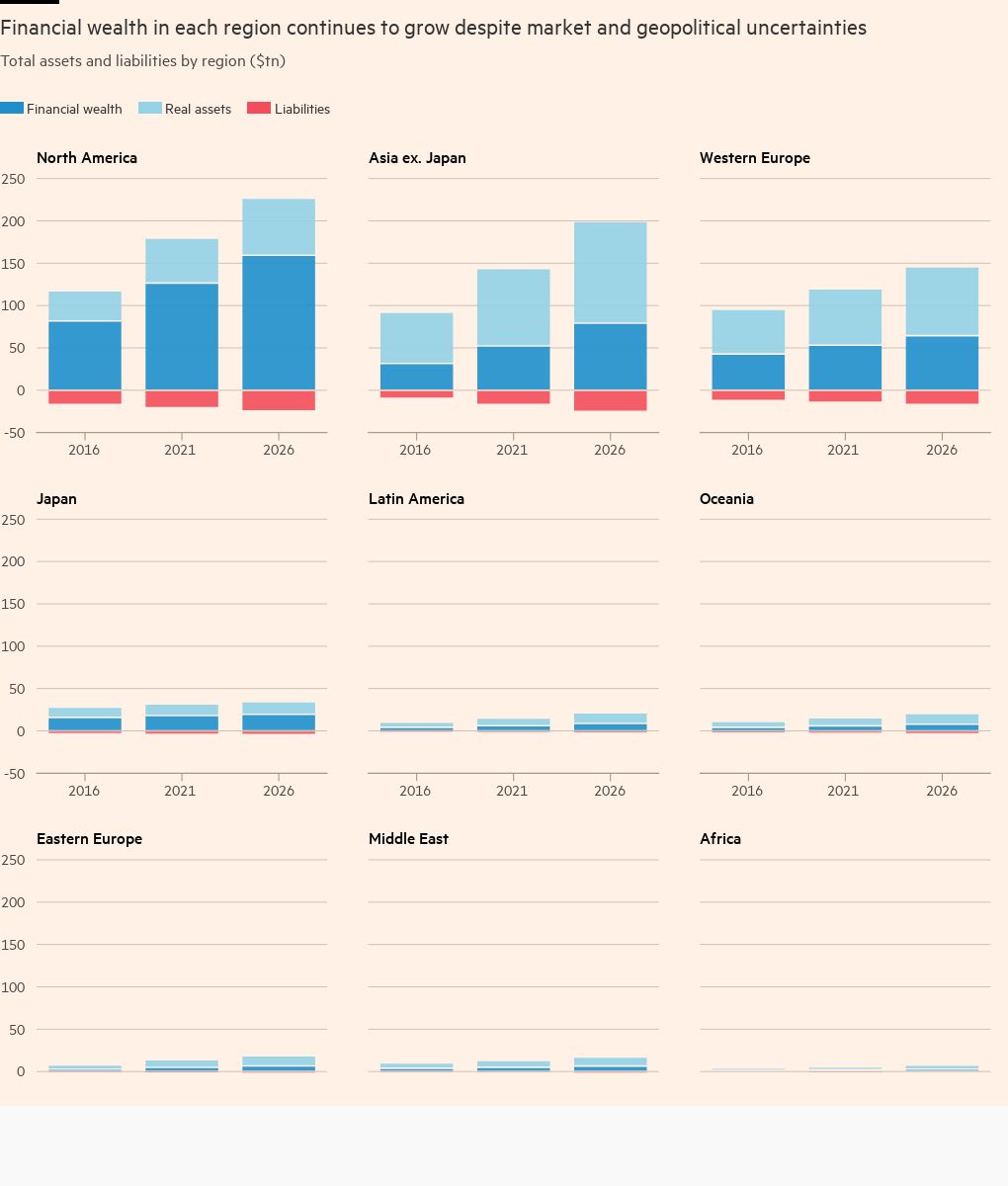

Not so, say the experts at management consultants BCG, in the company’s annual report on global wealth. Far from staring into an abyss, they are looking upwards and see the world’s stock of financial wealth growing steadily over the next five years.

In their base case, global financial assets are forecast to rise by 5.3 per cent annually to 2026. That assumes that Russia halts its invasion of Ukraine this year and geopolitical tensions ease, even though sanctions on Moscow would remain in place until 2025.

Remarkably, a longer conflict in Ukraine has only a modest impact. Even if the fighting lasts well into 2023 and sanctions increase, the effects on wealth accumulation will likely be limited as long as there is no military escalation. Under these circumstances, BCG forecasts growth in financial wealth of 5.0 per cent. So almost the same.

To be fair, the forecast does involve a substantial slow down in wealth accumulation compared with the recent past. Financial asset growth in the decade to 2021 was 7.2 per cent annually. But still, given the role of rising financial markets in boosting assets, it might be expected that a time when conditions are likely to be choppier would see wealth accumulation running into the sand.

BCG points to the remarkable resilience of wealth accumulation during the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic shock. “While not immune to market volatility, global wealth portfolios have rebounded from recent shocks,” the authors write.

On top of this, inflation may boost wealth for canny investors by driving up the shares of inflation-resistant companies — and by encouraging them to switch money out of fast-depreciating cash into securities.

However, at the heart of the BCG forecast lies the increasing geographical diversification of the world’s wealth away from the Atlantic to the Asia-Pacific region. Even with its economy in the doldrums, China continues to accumulate money as do its neighbours. These are countries very far from the Donbas.

The Asia-Pacific region is not immune to the impact of higher energy and food prices, but the effects are muted by distance and by its own economic dynamism. The same is true, if to a lesser extent, for Africa and Latin America. Oil producers everywhere are seeing a bonanza, not least the Gulf states.

One consequence for the rich — and their advisers — is the seemingly relentless rise of Hong Kong and Singapore as global wealth management centres. BCG forecasts that, by 2026, Hong Kong will overtake Switzerland as the world’s biggest centre for cross-border assets, a shift of historic proportions.

And, say the writers, it will come despite a moderate exodus of money from Hong Kong to Singapore (and elsewhere) because of Beijing’s political squeeze — although there will still be bigger inflows from the mainland to Hong Kong.

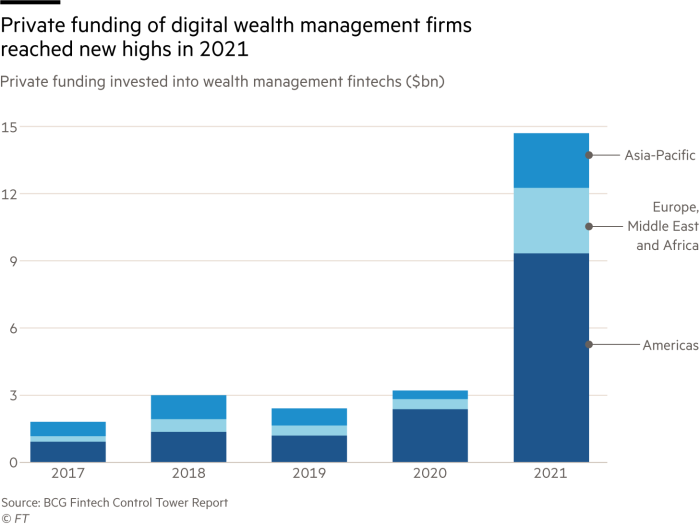

Does this spell the demise of traditional centres of wealth management? Not necessarily. BCG argues that high-tech wizards in Zurich, London and New York have every chance to capitalise on the digital revolution — and turn the sometimes-clunky tech services offered in wealth management into something genuinely appealing. That’s all very promising, especially if you are a tech-minded wealth management company with a decent client list.

But, history suggests that BCG’s views should be read with a degree of caution. Wars have a habit of running out of control; inflation is not always as transitory as the authorities say; and a market upheaval can do lasting economic damage, as with the global financial crisis. It’s perhaps bad timing for rose-tinted glasses in the wealth industry.

Stefan Wagstyl is the editor of FT Wealth and FT Money. Follow him on Twitter @stefanwagstyl

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment

Comments