Cracks in finances put business schools at risk

Simply sign up to the Business education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The past two months have seen the mood in US business schools take on a new optimism as a flurry of philanthropic gifts have signalled that not only is the US economy now in better shape, but wealthy donors are putting their hands in their pockets once more.

Both the Rady School at UC San Diego and the Anderson school at UCLA received $100,000m gifts, while Boston University’s business school changed its name to the Questrom school in acknowledgment of a $50m pledge.

Yet even the most optimistic dean concedes this outpouring of philanthropy does little to paper over the real cracks in business school finances, particularly for those in the public sector.

“It is clearly true that deans are more concerned these days about where the money is coming from,” says Bernard Ramanantsoa, who has been head of HEC Paris since 1995. “Costs are going up and state revenues are decreasing,” he says, in a financial pincer movement he describes as an “effet ciseaux”.

Aspirations to be part of an elite cadre of research-led institutions, combined with the belief that MBA schools have to offer expensive global courses and experiences in order to compete, have resulted in an inexorable rise in costs for business schools.

“Everybody wants to be research driven and global,” says Steef van de Velde, dean of Rotterdam School of Management at Erasmus University. “It’s staggering what you have to pay to recruit a top professor, especially in finance or accounting.”

Such academics can command salaries of $400,000 and more, with strong demand from developing business schools in Asia, particularly China, driving up their market value.

In addition, there is an unrelenting spiral in the demand for quality facilities and services, points out Arnoud De Meyer, president of Singapore Management University. By promising MBA students a high rate of return on investment shortly after graduation, “we have shot ourselves in the foot”, he says. “Students come in with high levels of expectation,” he says, and that is expensive.

On top of this, fees have been heavily discounted to attract the top students as application numbers dwindle, says Prof De Meyer. “We don’t use the word discounts, we say scholarships. But they are discounts.”

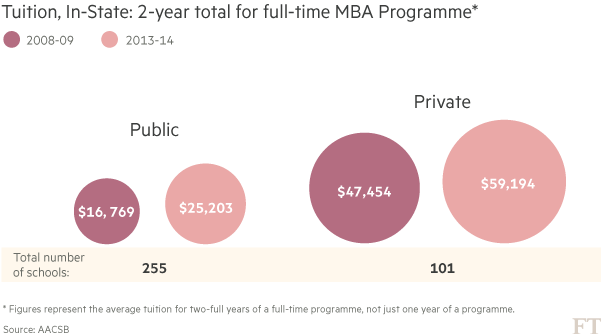

Faced with these issues, deans have striven to diversify income sources, both by increasing student numbers and fees. In the five years from 2009 to 2014, private schools in the US increased MBA fees by 25 per cent, according to data from the AACSB, while state schools raised instate tuition 50 per cent.

Strong resistance from the market over the past two to three years means that few now believe putting up fees can continue to fuel growth. “I don’t think we’re going to see an increase in tuition fees,” says Alison Davis-Blake, dean of Michigan Ross. “The notion that we can get ourselves out of this problem by increasing revenues [for each programme] is false.”

Online learning

All-out effort needed in tech

Online technology brought the promise of scale and scope to business school teaching, but after years of experimentation, many believe online teaching now represents a cost rather than an asset.

“Moocs (massive open online courses) cannot be developed into a profitmaking offering,” says Ulrich Hommel associate director of quality services at the European Foundation for Management Development (EFMD). Many schools are now looking at embedding online technology in courses, but Prof Hommel warns that it is a risky game.

“Everybody is investigating the potential of online and teaching, but it has to be an all-out effort. You have to work out what your plan is.” The big question, he says, is “how do you get into a trajectory where you are in the forefront of teaching and pedagogy.”

As government funding dries up and MBA numbers fall, business schools are being forced to be more entrepreneurial in the way they raise money, he says, and that may lead many to make rash or risky investments.

While he believes the elite group of top schools will continue to thrive, second and third tier schools will have to get a tighter grip on their finances if they are to compete with the growing number of for-profit institutions, he argues. “They [business schools] don’t know where their money goes. [By comparison] the for-profit business schools are becoming more mainstream and they are extremely cost-efficient.”

A recent survey conducted by Prof Hommel of EFMD member schools showed that most business schools were only just beginning to address the issues of risk. In particular, only 22 per cent of the sample schools, the majority of which are in Europe, follow what Prof Hommel describes as the state-of-the art corporate practice of assigning the responsibility for risk management to the senior management. team. Instead, 61 per cent of business schools entrust the dean with the task of managing risk, along with all his or her other duties.

“I just don’t think it’s a credible answer,” concludes Prof Hommel.

She points to a diversification in programmes across many schools to address the issue, in particular the launch of specialised masters degrees, undergraduate boot camps and joint degrees with other institutions, both traditional universities and corporate academies. She also believes there will be more short courses, for life-long learning. “That may not be high price, but it will be high volume.”

Chicago Booth dean Sunil Kumar argues this fragmentation will be beneficial. “There is no reason to believe all schools, whatever their financial resources, should do the same things,” he says. Booth, for example, recently increased the size of its part-time weekend programme.

To address the growing imbalance between income and outgoings Prof Davis-Blake believes the first stop must be for schools to get their house in order. “There are rules for productivity and efficiency gains and they have to happen.”

But most deans are turning to philanthropy for salvation. It is a policy that brings its own limitations as well as benefits.

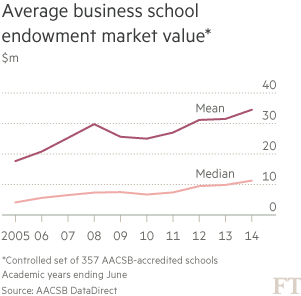

Though the yield from endowments has traditionally run at 4 or 5 per cent, the recent financial crisis meant returns were often halved. Things are now improving again, says Sue Cunningham, president of the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (Case). “They’re just about coming back, but only just.”

But even with high returns, endowment income can only ever be part of the answer, says Prof de Meyer, who points out that most schools get only about 10 per cent of their operating costs from endowments. And he believes there are geographical limitations. “The model of business schools based on endowments has worked very well in the United States. But when you look at the reality it is a small group of top institutions that get the large amounts,” he says. “Outside the US I cannot find one school that is built on an endowment.”

That will change, argues Prof Kumar, who points to philanthropic giving ro US universities from overseas citizens. “In the case of Asia and Latin America it is only just getting started.

The push for donations has forced some schools to reassess their structure. In France, the grandes écoles have had to pioneer a French law to enable them to adopt a status that will encourage fundraising (see below). At the Anderson school at UCLA it has been a similar story. Dean Judy Olian worked for several years to persuade the University of California to change the business school’s status to give more freedom and encourage fundraising.

Last month’s $100m gift would seem to justify the changes, implemented in July 2014. Before the change in status “people thought we ere supported by the state in a way that it couldn’t support us,” says Prof Olian, and so were unwilling to donate.

These institutions will not be the only ones that need to adopt a new strategy or structure if they are to compete. Prof Davis-Blake warns of what she calls a “bifurcation of the market”, in which the top, well-funded business schools will draw away from the rest of the pack, leaving second and third tier schools to flounder.

“I do think a number of business schools will have to decide they are not a research business school, that they will be an excellent teaching school,” adds Prof Meyer. More mergers are also on the cards, he predicts. But even that will not save some schools, he believes. “We are under attack. There is going to be a rationalisation of the market, that I am convinced of.”

Prof van de Velde is even more candid: “You have to be the first mover and then hope that other people go bankrupt or give up.”

Other features in this series:

Short tenures signal leadership void

Industry savvy teaching keeps courses in the game

————————————————————

Comments