How bad is the US economy?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Yesterday’s letter sniffed a little blood in the market water, so of course stocks rebounded immediately. But if you think the market is in great shape, we suggest you look, for example, at the Russell 2000, which is still down 10 per cent from its November peak, and has gone nowhere since February. We still think this market looks a bit ropey, as our British colleagues might say. Email us with corrective doses of optimism: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

American pessimism

I was very much struck by this interview in The New York Times with the Democratic pollster Brian Stryker. Following the recent Republican victory in the governor’s race in Virginia — a US state President Joe Biden won easily — Stryker conducted a series of focus groups with voters who had voted for Biden last year and then for the Republican gubernatorial candidate, Glenn Youngkin, this autumn.

The results of his interviews are captured in this memo. The bit that matters for Unhedged is this:

“Voters believe the economy is bad, and no amount of stats can change their mind (at least in the short term). Jobs numbers, wage numbers, and the number of people we’ve put back to work don’t move them . . . [the numbers] will have limited impact when people are seeing help wanted signs all over main street, restaurant sections closed for lack of workers, rising prices and supply disruptions. Even where things are getting better, Biden doesn’t get credit.”

People don’t like inflation. Everyone knows this. But the paragraph is nonetheless striking. People don’t like seeing jobs wanted signs? Those should be evidence of a strong economy. Americans, it seems, are seeing only one side of things. If they continue to do so, the political ramifications will be significant: the Democrats are going to get absolutely smoked in the midterms in 2022, and maybe in the next presidential race too. That would matter to investors.

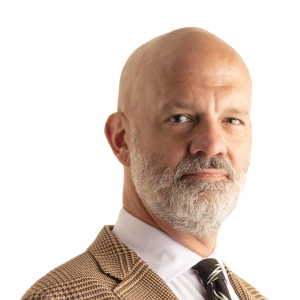

Here is a (Christmas-coloured) chart of the phenomenon Stryker is talking about. It shows real (inflation-adjusted) consumer spending and results of the Michigan consumer sentiment survey. The yellow bit shows what real spending would have done if it had stayed on its pre-Covid five-year trend. We are almost exactly where we would have been. The US consumer is back! Even adjusting for inflation! But sentiment remains a disaster (data from the Federal Reserve):

Part of the issue, as Greg Daco of Oxford Economics pointed out to me, is that the Michigan survey puts a lot of emphasis on buying conditions (“is now a good time to buy”, and so on) and it is very sensitive to inflation. Other surveys, such as the Conference Board’s, which put more emphasis on the labour market, look a little less bad.

But something very odd is going on, all the same, as Don Rissmiller of Strategas highlights. Sentiment surveys are generally split into two broad components: current conditions and future expectations. As a rule, the current conditions aspect correlates with employment levels, and the expectations component correlates with asset values (stocks, houses). Right now, employment is good and getting better, and asset prices are very strong. But both aspects of sentiment, current and expected, are lousy.

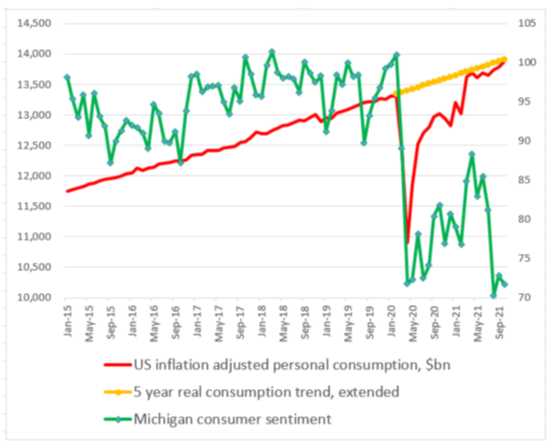

Rissmiller suggests that the problem can be seen in the mix of spending. Here is real personal expenditures on goods and services, again with their pre-Covid trends drawn in:

We are spending too much on goods and too little on services, and Rissmiller thinks this just does not feel good: “I’m cancelling my vacation, but I’m buying a new air fryer.” If Rissmiller is right, then the sentiment problem is not going to get better until the medical situation gets better. By extension, the political future of the country depends on Covid.

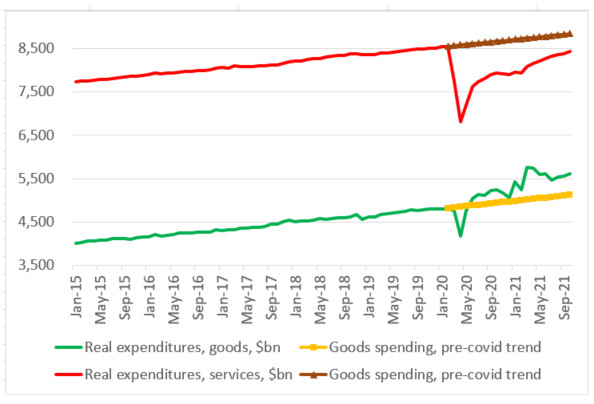

There is no doubt that inflation is not helping, though, and there is some reason for optimism on that front. Far and away the most important is what has happened to the price of crude oil since the end of October:

This will not take long to feed through to prices at the fuel pump. Perceived inflation is about to get better. And given yesterday’s news of a supply agreement with the Saudis (which follows “a charm offensive by Biden administration officials that included an effort to reframe the relationship between the US and the kingdom”) the trend may continue.

Fuel prices are not alone. As Paul Ashworth of Capital Economics argued to me, supply overall is getting just a little bit better. Some measures of shipping costs are coming down, backlogs at west coast ports are marginally improving, and automotive sector production has rebounded slightly. But, he says, “it’s going to be a slow, uneven process”.

It can’t happen slow enough for the Republicans, or fast enough for the Democrats.

PFOF redux

In the past, we have argued that payment for order flow is not very important, because retail investors only lose, if anything, tiny bits of money to it, and big traders can fend for themselves. But smart people disagree, so we’re still following PFOF.

Remember the basics. Imagine a simple retail trader, call him Rob. He buys a stock at a given price because he thinks the price is fair. The big institutional traders know he is not trying to trick them. In the industry jargon, Rob is “non-toxic”.

Market makers such as Virtu and Citadel Securities, who make money from the bid-ask spread, want Rob to trade with them because he doesn’t know anything they don’t. A more cunning trader, call it Wu Capital, might instead send lots of small orders to different trading venues. That could leave any one of these vendors holding the bag, should Wu Capital’s many small trades move the overall market quickly.

A broker such as Robinhood can therefore demand payment from market-makers in exchange for sending them non-toxic retail orders.

The problem when thinking about PFOF is that it creates quantifiable benefits but hard-to-quantify costs. The benefits come from the “price improvement” Rob receives from market makers — who can usually get advantageous prices on non-public trading venues. The market maker is buying at a price Rob can’t get on public stock markets, and passes some of the savings back to him.

The costs, meanwhile, come from the fact Rob doesn’t control how much of the savings he gets. Only the broker and market makers do. Larry Tabb, Bloomberg’s head of market structure research, reckons as much as $18bn is made off of bid-ask spreads, which is split between market-makers and brokers. Is this a good arrangement?

We chatted with Stephen Sikes, chief operating officer of Public.com, a brokerage that makes a big deal of the fact it doesn’t use PFOF. Instead, for each trade, Public scans 28 different public exchanges and non-exchange venues for the best price. Brokers and market makers, he says, don’t look for the best price for the individual trader. They look for a good enough price — a little bit better than the national benchmark — that maximises their own profits.

It is still a very marginal difference, fractions of pennies a share. For individual investors it doesn’t matter. But in aggregate, the cost to society is significant. Surely there are more productive uses for the money?

Some suggest banning PFOF outright, but the practice might easily re-emerge in a different form. A better place to start, Tabb and Sikes agree, is for the Securities and Exchange Commission to start requiring more disclosures from retail brokers. Currently the agency requires market makers, but not brokers, to release monthly data on how well they executed their trades. Changing this could force brokers to compete on more transparent prices.

The problem regulators have is that the current system creates concentrated benefits and diffuse costs. No one is getting screwed. Rather, it is as if everyone is paying a very light, but probably pointless, tax. This may not be possible to fix, but more transparency is worth a try. (Ethan Wu)

One good read

A key number, cited in Unhedged and many other places, might be a bit deceptive. A paper by Kenneth Rogoff and Yuanchen Yang found that the property sector accounted for a terrifying 29 per cent of China’s gross domestic product. But as it turns out there are less frightening and more convincing ways to tot up the sector’s contribution. A good catch by The Economist.

Comments