Colombia aims for post-pandemic tourism market

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It may be a while before crowds of foreign visitors return to Colombia’s top tourist attraction, the beautiful walled city of Cartagena on the Caribbean coast.

In normal circumstances, thousands descend from cruise ships and international flights to wander its narrow streets, relax in its boutique hotels and gaze at its graceful, colonial-era architecture and balconies draped with bougainvillea.

But coronavirus is likely to diminish city tourism, at least until a vaccine is developed. Travel industry experts say that, in a world grappling with Covid-19, tourists will visit quieter, less urban and more sustainable destinations that allow them to take off their masks, explore backwaters and forget about the pandemic – at least for a couple of weeks.

Colombia is well-equipped to provide such tourism and as it emerges from lockdown, it wants to encourage it.

“There will be a big shift in travel trends, and the most obvious change will be that people will want to travel in smaller groups to non-crowded destinations,” says Julían Guerrero, Colombia’s vice-minister for tourism. “We’re really working on positioning Colombia as a sustainable tourism destination in the long term. We don’t want to attract mass-tourism if it’s not sustainable.”

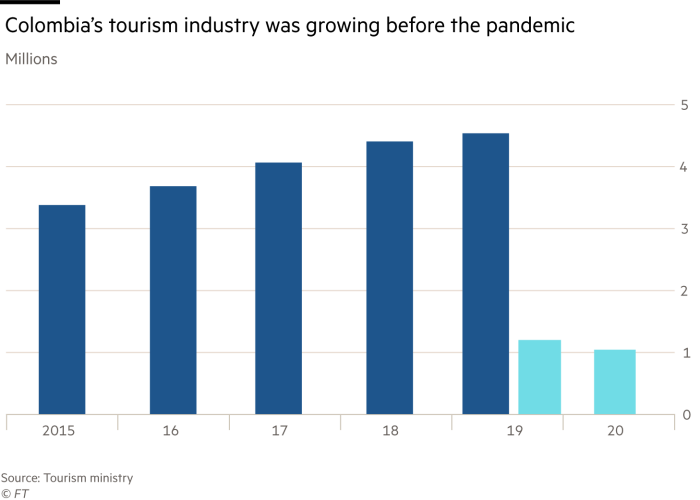

Mr Guerrero points out that Colombia is the size of France, Spain and Portugal combined. But while those countries have a combined population of more than 125m and attract about 180m tourists a year, Colombia is a country of 50m and receives just 4.5m visitors. For travellers tired of the crowds at the Louvre, Colombia’s wide, open spaces could prove relief.

The country is one of the most biodiverse on the planet and with about 2,000 species, it has become a destination for bird-watchers. Its vast tracts of Amazon rainforest are fertile ground for horticulturalists, herpetologists and those who want to escape urban life and experience the jungle.

Colombia’s decades-long civil conflict has helped preserve these wildernesses. For decades, much of the country was off limits to visitors because it was too dangerous. Now, these areas are opening up to tourism and many are unspoilt – a welcome if unintended consequence of war.

Colombia is also establishing a reputation for sports and adventure tourism, fuelled in part by the success of its cyclists. In Boyacá and Cundinamarca – green, mountainous provinces in the heart of the country – companies offer cyclists the opportunity to test their stamina on the roads where Egan Bernal, 2019 Tour de France winner, honed his talent. Further north in Santander province, tourists can paraglide over the Chicamocha canyon, one of the deepest valleys in Latin America.

The little-explored Pacific coast has become a draw for whale-watchers while on the Caribbean coast, dozens of eco-lodges are popping up, offering tourists a low-key alternative to the big hotels.

While most seek to give visitors a chilled-out beach experience, some offer the chance to learn about the indigenous communities of the nearby Sierra Nevada mountains. The Taironaka Archeological Ecolodge, for example, sits next to the remains of a long abandoned indigenous village that was covered in thick undergrowth until just a few years ago.

The lodge has a small museum of artefacts found when the village was unearthed. Visitors can take a bird-watching walk through the forest with a guide from the local Kogui indigenous group. They can even have a “Kogui wedding” at the eco-lodge, presided over by a spiritual leader.

“The ruins are our unique selling point,” says Tatiana Torres, the eco-lodge’s owner. “Obviously we want our visitors to relax but we also hope they’ll learn something while they’re here and contribute to the local community.”

With more than 80 indigenous groups speaking a dozen languages, Colombia has potential for this style of community-based tourism. It is also developing “post-conflict tourism” projects, generating jobs for people who just a few years ago were fighting the state in the ranks of leftwing guerrilla groups.

“Many of the regions that were worst affected by the conflict are spectacularly beautiful, and we think we can use tourism to consolidate peace,” says Mr Guerrero, for example by encouraging ex-combatants from the Farc and other groups to work in the industry. “A local person with a pair of binoculars is a tourist guide in the making.”

According to the tourism ministry, several companies, including Impulse Travel, History Travelers and Awake Travel, are operating ecotourism ventures in a responsible way, by involving indigenous communities and ensuring they receive a share of the proceeds. But other, less scrupulous companies are operating too, it adds.

For those who want to invest in Colombia rather than simply visit, the government offers a number of incentives. Anyone opening an eco-lodge, for example, pays tax of 9 per cent compared with a basic corporate tax rate of 32 per cent.

The government has also announced specific measures to help recover from coronavirus. It has cut tax on international air tickets and on jet fuel from 19 per cent to 5 per cent to help cash-strapped airlines. The state has also set up credit lines for the sector, and in some cases, covered part of the wages of employees, allowing companies to keep them on payroll.

It is too early to assess whether these measures will work. Beaches and flights opened only in September.

The government has offered a $370m loan to Avianca, the airline, which critics say is a bailout of a company that was already in financial trouble and is effectively owned by foreign shareholders. Other airlines say the government has been over-generous to Avianca and the loan has been challenged in court.

These measures highlight the importance of the industry to the Colombian economy. Tourism accounts for 9 per cent of Colombian jobs and last year generated $6.7bn, making it the country’s biggest generator of foreign exchange outside the mining and oil sectors. President Iván Duque frequently refers to tourism as “the new oil”.

But in the post-Covid world, Colombia wants to do things differently.

“This is not the moment to build a mega-hotel on a beachfront. It’s the time to build a smaller lodge catering to fewer people,” says Laura Durana, director of Acotur, the Colombian association for responsible tourism. “That’s the sort of tourism people will want”.

This story was amended on October 28 to make it clear that the tourism figures in the chart are numbers of actual visitors, not projections.

Latest coronavirus news

Follow FT's live coverage and analysis of the global pandemic and the rapidly evolving economic crisis here.

Comments