Gianni Jetzer, the man behind Art Basel’s supersized Unlimited exhibition

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Reinvention is difficult in the event-heavy art market, but Art Basel arguably broke the mould when, in 2000, it launched Unlimited, a separate showing of supersized works that runs alongside its main fair. The man behind the monuments for his eighth and final year is the measured, seemingly forever young Gianni Jetzer, 49, who is also curator-at-large at Washington DC’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden.

“It’s sad, on the one hand, that this is my last Unlimited, but it’s also a natural process for the fair to change its affiliated curators, and eight years is quite a long time,” Jetzer says over Skype from his home in New York, looking a little relieved. His role at the Hirshhorn will keep him busy for a while, he says, so any other plans are yet unformed (or at least he is keeping them to himself) and his replacement has yet to be named.

Having previously presided over Switzerland’s Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen and the Swiss Institute in New York, Jetzer, who was born and bred in Zurich, acknowledges that he is attracted to the European kunsthalle model for contemporary art, in which institutions are not committed to a permanent collection.

Impermanence is part of Unlimited’s appeal, Jetzer says. “I think of the format like a high-frequency arts festival,” he says, citing approximately 80,000 visitors across its six-day run. Unlike in a kunsthalle or festival, though, the works in Unlimited — which number 75 at this year’s outing, and have been as many as 88 in the past — are generally for sale, with prices often commensurate to their size.

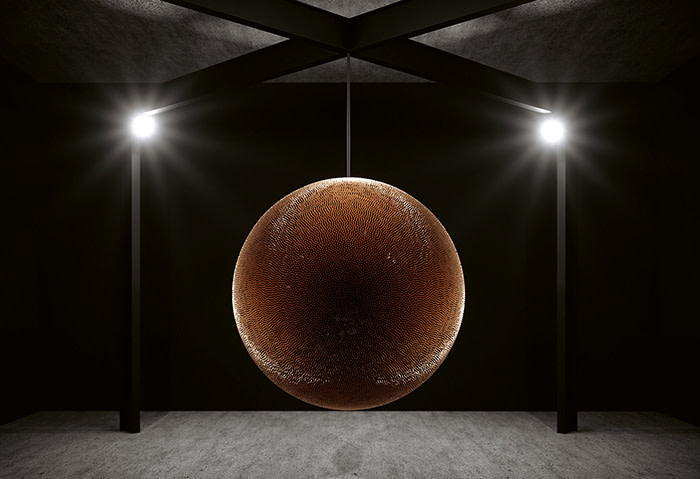

Mapping the growth of high-spec private museums around the world, previous notable purchases from Unlimited have included Robert Longo’s “Death Star II” (2017-18), a work made of bullets and priced at $1.5m, that went to Germany’s Schauwerk Foundation museum last year (through the galleries Thaddaeus Ropac and Metro Pictures), and a 2004 Jason Rhoades neon installation that went to Dasha Zhukova, founder of what is now the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, for about $1m in 2011.

“I’m not informed by sales, but they are a reality of production that I can take advantage of,” Jetzer says, adding: “If galleries don’t generate income, they won’t come back.” He also feels that the “mercantile pattern” that underpins Unlimited, and fairs in general, makes art more accessible. “The barriers to entry are lower. People whisper in museums, but never in a fair.”

Curating a section of the fair in which size is important has not been without its challenges. “The most difficult aspect is to have the nerves to go through the production and setting of these works,” Jetzer says. “Every gallery wants their artist to get the best showing, front and centre, which is understandable, given what they’ve spent. We work hard to have a democratic master plan, which gets updated and corrected about 40 times,” he adds.

Jetzer cites Hanne Darboven’s significant and gigantic “Kinder dieser Welt” (“Children of the World”, 1990-96), a 500 square-metre installation comprising books, toys and more than 2,000 musical scores that came to Unlimited in 2014, as one of his most challenging installations to date.

This year’s edition brings a new test, he says, in the form of a performative work by the Kosovo-born Sislej Xhafa. In “ovoid solitude” (2019), a performer will sit silently at a corrugated storefront all week, ostensibly selling the rows of eggs stacked high behind him (the work is for sale with Galleria Continua).

The performance piece will be one of many sure-fire Instagram hits. Jetzer is not immune to the fact that the rise in Unlimited’s popularity has coincided with the growth of social media, but it’s not something he dwells on. “Sure, Instagram has influenced all of us in some way, but it’s not how the show functions,” he says. He does however concede that there will be other snap-happy pieces on view, including Monica Bonvicini’s “Breathing” (2017), a large broom made up of leather belts with metal buckles that will hang from the vast Messeplatz ceiling and noisily sweep its floor (through Galleria Raffaella Cortese, Galerie Peter Kilchmann and Mitchell-Innes & Nash).

One trend Jetzer says he has witnessed over the years is the shift from galleries presenting contemporary works towards a greater showing of historical pieces. Among those he highlights this year is a Felix Gonzalez-Torres group of 55 photographic puzzles, made between 1987 and 1992, and shown together for the first time at this year’s fair (through David Zwirner). “It’s great that Unlimited can bring such a one-of-a-kind opus,” Jetzer says.

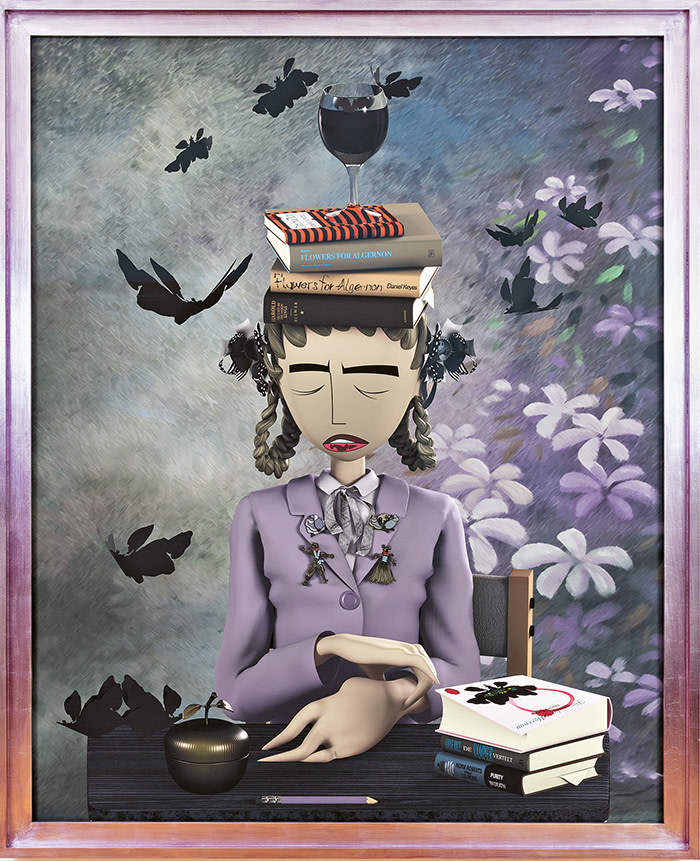

Contemporary works still dominate, though, and Jetzer highlights the youngest artist in his show, Bunny Rogers (born 1990), who brings a new series of 15 computer-generated self-portraits that explore the ambivalent reactions to the 1999 Columbine High School massacre incorporating the artist’s discovery of a teenage subculture that obsesses about the shooters (Société gallery).

“Gianni’s democratic approach of including both newcomers and overlooked luminaries creates a very interesting dialogue,” says Iwan Wirth, president of Hauser & Wirth. His gallery brings six works to Unlimited this year, spanning Fausto Melotti’s copper “La Sibilla (“The Sibyl”) from 1981 to Zoe Leonard’s 1,033-book installation “How to Take Good Pictures”, made for her 2018 Whitney Museum of American Art retrospective (with Galerie Gisela Capitain and Galleria Raffaella Cortese). Overall, Wirth says, “Gianni has been able to give Unlimited a coherent form and has really pushed it into the form of a critical exhibition.”

Jetzer is a curator who is happy to get stuck in. Back in 2015, he even became part of an Unlimited work when he replaced Julius von Bismarck for a couple of hours and sat in the German artist’s nausea-inducing, revolving cement bowl, “Egocentric System”. “The work is one of my highlights from my time at Unlimited, but the experience was super stressful. The only way to escape it was to nap and when I woke up, it felt violent,” Jetzer says. No wonder he’s a little relieved to pass on the baton.

June 13-16, artbasel.com

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments