Slow progress on race hampers business school diversity push

Simply sign up to the Business education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

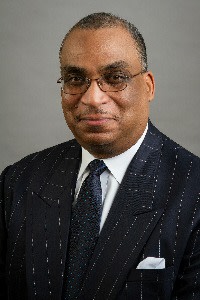

Steven Rogers offers one nuance to his scathing critique of efforts by Harvard Business School and others to step up their training of black managers in the US: “No school was better [than Harvard] and all of them were horrible.”

Rogers quit the Harvard faculty as a senior lecturer in finance in 2019, after feeling “heavy disappointment” with the school’s slow progress on diversity, and has since taught his own black business leadership and entrepreneurship courses across the US.

He would like to see more outreach and support programmes at business schools to help recruit and retain students and staff; greater production and use of compulsory case studies with black protagonists; and — more radically — direct investment by university endowments in black-owned businesses.

His sentiments reflect broader frustrations by under-represented groups seeking access to business education: while diversity is viewed as both ethically necessary and pragmatically important for corporate success, the barriers remain significant to business schools stepping up their response.

Business schools have made progress in recruiting women faculty and students — even if most remain far from achieving gender parity. In the past decade, the top 100 FT ranked global MBA programmes have increased the proportion of women students from 30 per cent to 37 per cent on average, and among faculty from 24 per cent to 29 per cent.

Many schools have refreshed their curricula in line with changing societal expectations, with a greater focus on topics such as sustainability. However, the record remains patchy on addressing imbalances among traditionally excluded groups, such as black students and faculty.

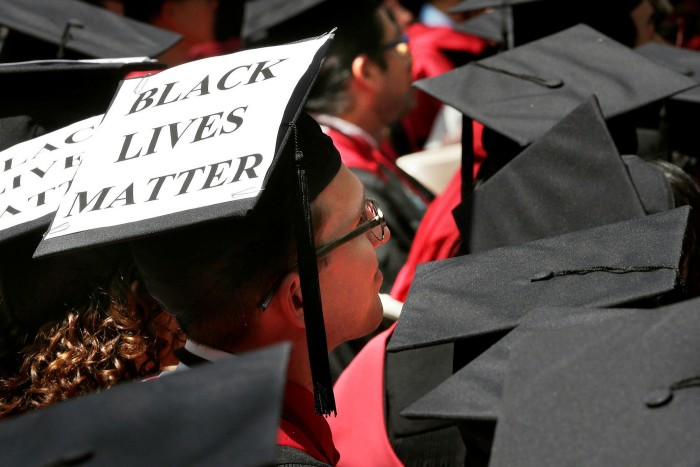

Sparked in part by the Black Lives Matter movement, Harvard Business School last September revealed a racial equity action plan. It has yet to share specific targets, but is preparing to appoint a chief diversity and inclusion officer alongside 13 new faculty, of whom four identify as black or African-American.

The school says every course in its required curriculum will use at least one of the 60 teaching case studies it has featuring a black protagonist, and it is developing a system to track new ones under development. It has also launched an elective on scaling minority businesses, and plans to expand procurement from black-owned businesses.

Harvard is not alone. “We need to work on the diversity of the student body and, once they come in, how to ensure that we have an inclusive environment for them,” says Costis Maglaras, dean of Columbia Business School. “We would like our faculty, cases, guest speakers and role models to match the demographic of our student body.”

But reform is not simple. A challenge for business schools is defining under-represented groups for which to improve access. For Rogers, author of A Letter to My White Friends and Colleagues, there is little doubt over those against whom historical injustices are greatest.

“As you go from country to country, the question is whether there is a group of people that have historically been discriminated against via colonialism or enslavement,” he says. “In every one, blacks have experienced anti-black racism.”

Piet Naudé, dean of the University of Stellenbosch Business School, says his priority is greater inclusion of South Africa’s black citizens after decades of discrimination under the apartheid regime. “It is a question of changing institutional culture away from the default white, patriarchal position,” he says.

Joseph Milner, vice-dean for MBA programmes at the Rotman School of Management at the University of Toronto, has broadened this focus to include “people of colour” — such as black Canadians and African-Caribbeans, but also Canada’s indigenous populations, such as the First Nations.

He has overseen new scholarships and the appointment of “executives in residence” with diverse backgrounds to share their experiences and offer mentoring. But he stresses the heavy legacy of the past: “First Nations have been part of the Canadian colonial experience, and the University of Toronto itself is seen as part of the colonial project. There’s a history,” he says.

Inquiries to global business schools by the FT identified other initiatives. Chinese institutions highlighted representation among those ethnic groups in the country beyond the majority Han population. In India, emphasis is placed on access to the lowest Hindu castes.

In the UK, one focus is on social mobility, seeking to attract those from poorer backgrounds. But these measures are primarily designed to improve opportunities for more marginalised British citizens to access undergraduate education, rather than fostering diversity and affordability on the postgraduate and professional training courses that typically charge higher fees.

In France, ESCP Business School has launched Chances Augmentées, a programme aimed at encouraging what it calls a more diverse “social and geographical” range of candidates for its business entrance exam.

Elsewhere, some schools highlight policies to identify and improve representation among military veterans, LGBTQ students, those from religious minorities, the physically disabled or those who are neurodiverse. One school cited “extreme old age” as an under-represented group on its advisory council.

A second problem is measurement itself. Some European business schools argue that a respect for privacy, enhanced by the recent GDPR legislation, limits their ability to collect and use monitoring data. France does not collect official statistics by race or ethnicity, arguing that such data could create discrimination and that all those with citizenship are equal under the law, regardless of background.

There are also ambiguities in how different groups are classified. Business schools have diversified their international intakes, appealing to students from other countries to create a greater mix in the classroom. But in the process, it becomes more complex to assess ethnic background and how far disadvantaged groups are being successfully targeted to promote social mobility.

“It’s almost impossible to pick apart,” says John Colley, associate dean at Warwick Business School. “It depends on what someone chooses to call themselves.” He points out that many of his institution’s intake are citizens of Commonwealth countries, but longtime UK residents.

Actions may be slow and complex to measure, but students such as Toni Morgan point to progress. She says she feels confident studying her EMBA at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, although she is just one of two black women on her course. “True diversity and inclusion is making space for different voices to be heard . . . to feel comfortable enough in your own skin to contribute to a conversation when you don’t feel it will be held against you.”

Comments