Off the wall – how the frame became an art form of its own

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

We’ve all been looking at the walls in our homes a little too much. So a rethink about how to present paintings and photography feels timely. Art lovers of all walks of life are looking to experiment with how they frame – or reframe – the pieces they love. From Perspex boxes to silicone, gilt edges to colour matching, the frames chosen by a clutch of international artists are pushing new boundaries.

“I’ve never known an artist not to be specific about framing,” says gallerist Sadie Coles, but the line between art and frame is increasingly blurring. Coles represents Matthew Barney, whose memorable Drawing Restraint series saw the artist encase his pieces in frames made from self-lubricating plastic. “That has morphed into polyurethane coloured plastic frames that are very much part of the total work,” says Coles. And it’s inspiring a new generation.

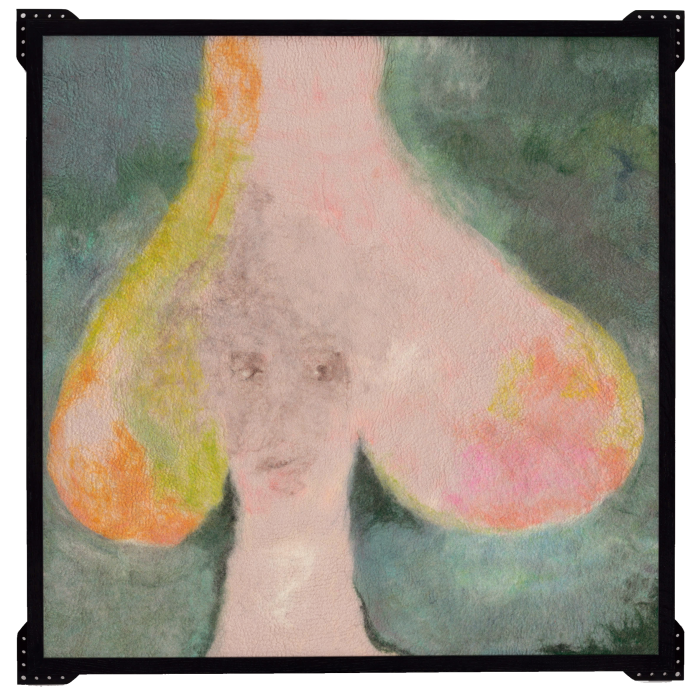

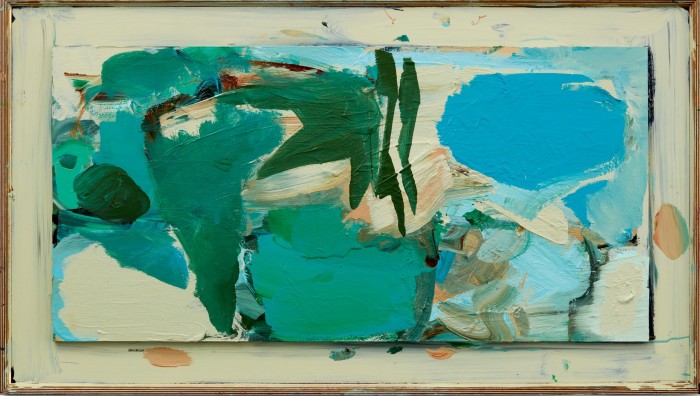

Katy Moran, who shows with Stuart Shave’s Modern Art, makes her frames integral to her paintings, covering them with the pigments that spill beyond the canvas. For these, she “picks up old frames from charity or salvage shops that spike my curiosity”, she says. “I’m interested in notions of taste and the relationship of the frame to art history.” Even when working with new frames, Moran experiments with colour, wood and linen. “You can really enhance and affect the reading of a painting with the right frame, but you can also ruin it with the wrong one,” she says. “To me, the frame is another tool to play with.”

Many leading institutions are also becoming bolder with their choices, says Harry Burden of Frame London, Dalston, which works with Whitechapel Gallery, the ICA and the V&A, as well as galleries such as Stephen Friedman, White Cube and Modern Art. In particular, Burden mentions the neon, gloss and pearlescent coloured frames created in collaboration with set designer Shona Heath for the Tim Walker exhibition at the V&A Museum last year. Private clients are following suit, and Burden says that collectors are becoming increasingly more open. “Some of our regular clients are willing to let us make bold decisions on their behalf,” he says. “Social media also helps to see and swap ideas. They often want something to reflect the choices they are making in other areas of their lives – frames crafted in sustainable materials or colours to match their walls. As people put more value in handcrafted objects, they also seem to appreciate the skill that goes into this level of framing,” he adds, highlighting the popularity of unusual natural woods like eucalyptus and redwood, as well as linen-wrapped mounts and boldly shaped slips.

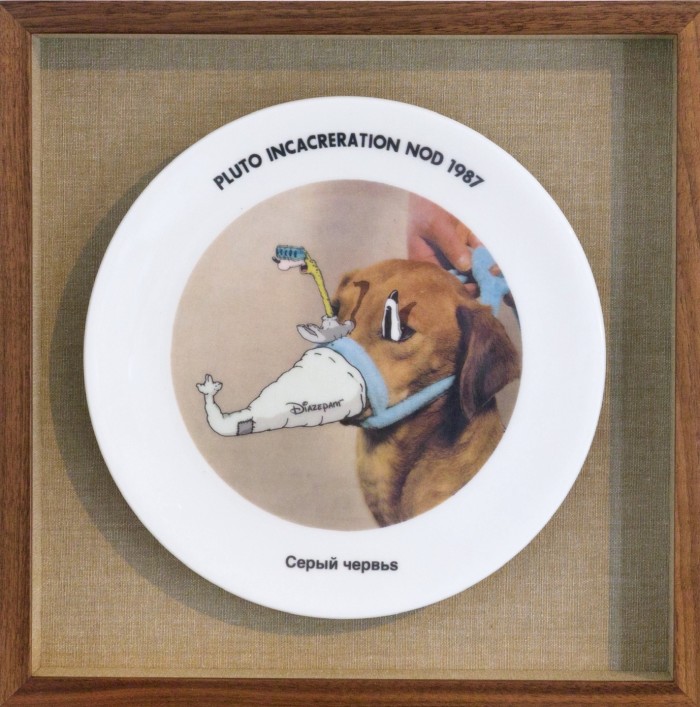

Frame London has recently launched a limited-edition artwork series, each with its own bespoke frame, that “celebrates the relationship between artist and craftsperson”. The first, by Aaron Angell, is in a frame inspired by the techniques used to make Tudor doll’s houses (£1,152). The latest is an editioned Enrico David collage (£3,600) with a bespoke frame echoing the subject matter. For David, who represented Italy at the last Venice Biennale and shows with Michael Werner, the frame has become a recent focus. “I started to think of the frame as a device to ‘support’ the image, acting as an imaginary orthopaedic apparatus aiding the image to stand, correct it, improve it, even: a visual caliper, of sorts.”

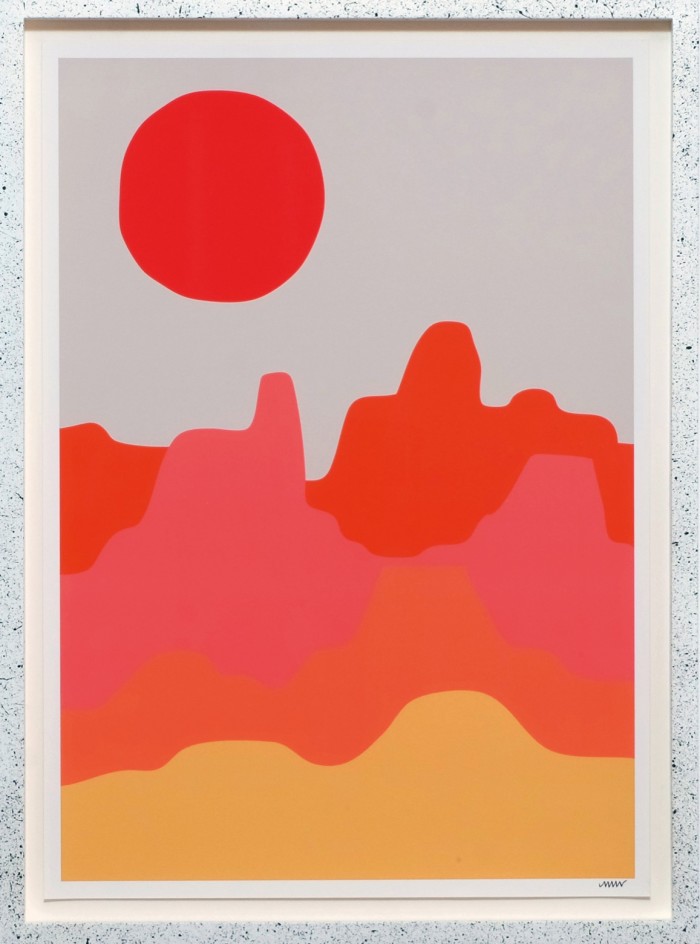

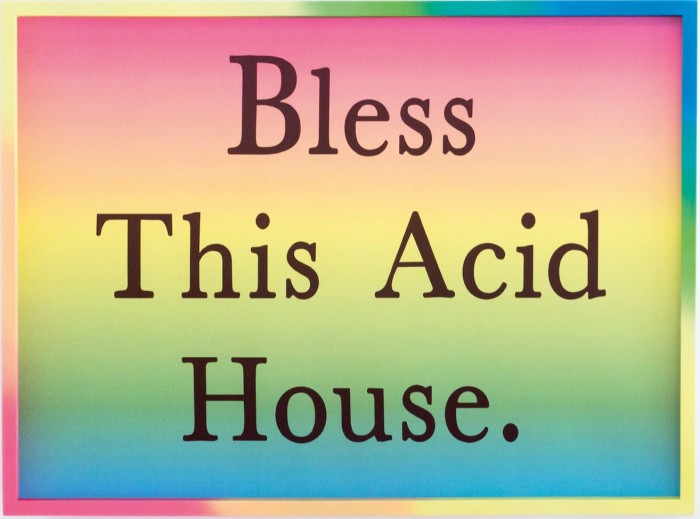

Frames that play with expectation are also the central focus of emerging Stroud-based RO Frames. Launched at the start of 2020, the company has framed works by Banksy, Tracey Emin, Terry Frost and Oskar Kokoschka. “We have always tried to offer customisations beyond just choosing a colour from a paint chart,” says RO’s Oliver Penman. For Jeremy Deller and Fraser Muggeridge’s Bless This Acid House, they created a five-colour, fade-effect frame that matched the colours of the artwork. The response online led to a flurry of new clients with requests for custom finishes such as multicolour, paint effects on wood and aluminium, joinery details and specifications regarding wood species.

On the flip side, John Currin, known for his satirical depictions of wealth, gender and class, chooses to hang his own work in opulent antique frames. “When you go to John’s house, the paintings that he has kept himself are in these beautiful Old Master frames,” says Coles. “As a gallery we pass that information on to collectors.” Specialists including Rollo Whately and Arnold Wiggins & Sons in London’s St James’s, as well as a number of Parisian dealers such as Maison Samson, are the go-to places for gilt antique frames – a growing investment in their own right.

“An antique frame can give works a more unique sense of identity,” says Brad Shar at New York framers Lowy, which framed Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, the most expensive artwork ever sold. Founded in 1907, Lowy works with the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Sotheby’s and the actor Steve Martin, a notable collector. “Lately some contemporary artists have requested to see mock-ups of their works in 18th-century Dutch and Spanish frames,” he adds. Other trends they are noticing are a lean towards the “Guggenheim box” (a double wall box frame) and reproduction frames based on modernist and minimalist styles. “A great frame can be a collector’s personal signature on an art acquisition,” says Shar.

While inspiration can springboard from many places – Instagram, exhibitions or interior-design trends – most importantly, it’s the conversation with framers open to experimentation that stimulate the best creations, says Frame London’s Emily Taylor: “A frame really needs to be considered.” Working in concert with the art they contain, frames can elevate it to the sublime.

Comments