Justin Welby: ‘We have a national case of PTSD’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

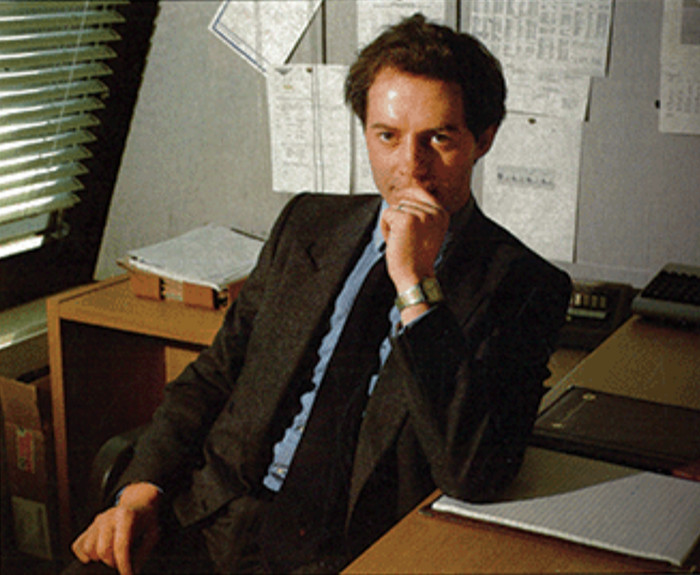

Almost as soon as I meet the Archbishop of Canterbury, he is apologising. All it needs is a momentary dither over which chair to take in his spacious office at Lambeth Palace. “We’re normally making it up as we go along!” he says, cheerily but contritely. Over the next two hours, he finds various other reasons to excuse himself: “I haven’t got any hair”, “I’m slightly deaf”, “I’m totally non-spatial”, “I’m really geeky”.

It’s very confusing: he’s the priest, shouldn’t I be the one confessing inadequacies? Certainly, before I can think about kicking the archbishop on any issue — personal or organisational — I sense that he has kicked himself harder already.

Yet to portray Justin Welby as just another apologetic Anglican would miss the point. The 65-year-old has the tidy demeanour of someone who scores Test cricket matches, but he hits out with the ease of a T20 specialist. Tasked with leading a divided Church in a disengaged nation since 2013, he has reoriented it from talking about sex to talking about poverty, housing and the evils of the banking industry.

He oversaw the overdue appointment of England’s first female bishops. He took on payday lender Wonga (and was embarrassed by the Church’s indirect shareholding in the company). He has regularly condemned the government, whether over welfare benefits or foreign aid. His tone is rarely Holier Than Thou, more an urging that we can be Holier Than Now.

Welby’s authority flows from his life experience: a difficult childhood with alcoholic parents and a decade working in the oil industry. “When had an archbishop been financially literate since the medieval archbishops who stole the country’s wealth?” asks Andrew Adonis, a colleague in the House of Lords.

Clerical critics, meanwhile, see Welby as too political, too managerial and insufficiently mystical. They were enraged by his acquiescence when the government closed places of worship during the pandemic, which they saw as epitomising his failure to stem the Church’s declining numbers.

Has the past year been a spiritual time? “For a huge number of people, it has,” says Welby, by now seated stiffly in an armchair. “It’s this sense of fragility: some recognition that unexpected, uncontrollable, intensely frightening external events don’t just happen to countries a long way away.”

In March 2020, while most people in Britain were doing all they could to stay out of hospital, Welby went into one. Although an inhaler-carrying asthmatic, he offered to act as a pastor in St Thomas’ hospital, next door to Lambeth Palace.

“I woke up in the middle of the night thinking about it, and got hold of the chaplain and said, ‘Do you need anyone?’ She said, ‘Half of our volunteers are over 70 so they’re sheltering, so yes, we need extra hands.’”

She would hardly refuse the archbishop, I say. “You can tell when they’re doing it because they think they ought to, rather than because they want to,” Welby says wryly.

He spent evenings praying with NHS staff, who had broken down in tears with exhaustion. He knelt at the bedsides of dying patients, who owing to distancing rules were able to speak to their families only on iPads. The experience has been “life-changing”, he says. “I was in there last night . . . What I’ve done for anyone else, I’ve no idea. But what it did for me, it brought me back close to God and close to people. That’s been one of the high points.”

The vaccine rollout will not wash away families’ grief; if anything it may deepen it, by emphasising how many losses were avoidable and by creating a jubilant mood that the bereaved cannot join. The Church estimates that six to eight million people have been unable to say goodbye properly to relatives, friends and acquaintances. “It’s a monumental thing that’s overhanging us. We have a national case of PTSD in one sense, which will show itself.”

One of Welby’s six children, Johanna, died aged seven months in a car crash in 1983. “Our own experience as a family is that you can become a helpless victim of grief.” He raises his left hand, and starts counting out practical advice. “What you need are: people to talk to and to share with; memories to hold on to; I would say prayers of lament and protest — why did this happen, why are we in this place?”

So it’s OK to feel angry at God, if you’ve lost a relative to Covid-19? “Oh yeees. It’s human! Feeling angry at God is absolutely fine. Psalms 22, 44 and 88. There are lots of psalms of protest, but those are real psalms of ‘God, this isn’t good enough. You are not doing the job.’”

He continues counting on his fingers. “But you also need to grab hold of moments of celebration. Attack the sensitive days or they will attack you . . . We have a member of the family who died many years ago, where we get together when we can as a family and we have a party on the birthday, and we celebrate the life of that person. A lot of people say they’ve started doing that and they’ve found it really helpful. We also buy a family present, something that’s useless and we’d probably not get but [which] is fun to have. There’s still the wrench and the sorrow. But there’s a real sense of ‘I’d prefer to feel that pain than that person never to have existed.’”

Justin Welby was born in London in 1956, almost exactly nine months after his parents married. His mother, Jane Portal, was a secretary to Winston Churchill; his father, Gavin Welby, was an unsavoury salesman. The couple, both alcoholics, separated when he was three. His father was ill-tempered; in retrospect, his behaviour was often “deeply abusive”, Welby has said.

In 2016, the Sunday Telegraph revealed that Welby’s biological father was in fact Anthony Montague Browne, Churchill’s private secretary. Welby’s mother, by then sober since 1968 and remarried to a Labour peer, explained that she had drunkenly slept with Montague Browne days before her wedding. The archbishop handled the news with notable calm: he called it a “complete surprise”, but added that his identity in Christ “never changes”. Does he feel bruised or liberated by his past being raked over? “Oh no, I don’t feel bruised. It’s just life in this job.”

As a boy, he was “average” at Eton, but made it to Trinity College, Cambridge. In between, he worked in a school in rural Kenya, and found God. He didn’t feel called to ministry, working instead for France’s Elf Aquitaine oil company, often travelling to Nigeria, then as treasurer for Enterprise Oil, which had North Sea fields.

Today, Welby is strident on climate change. Does he regret working in oil? “No, I learnt a huge amount there.” But surely he would now advise people not to work there? “I wouldn’t advise them not to.” Fossil fuels have maybe three decades left. “I’d much prefer to have good people trying to do the right thing in the oil industry than abandon it to those who don’t care what happens in the world around them.”

The Church Commissioners, the investment arm that manages £8.7bn, has seen “huge behavioural changes” at some extractive companies; it is now supporting a move to replace four directors at climate holdout ExxonMobil.

Welby described his application to succeed Rowan Williams as Archbishop of Canterbury as a “joke”, because he had only been Bishop of Durham for seven months. The Church was mired in arguments over gay sex and women bishops. Welby offered practicality and unity. Unusually, he could not be placed in any of the Church’s tribes.

Ordained aged 36 in Coventry, he had come up through Holy Trinity Brompton, a fast-growing evangelical church in west London, but broadened out. Williams’ tone was often mystical; Welby’s can be almost secular. One of his common prayers, I learn from a YouTube video, is “Oh God, please help me now.” Say it to yourself too quickly and it sounds blasphemous.

Welby is frank but not bombastic. In 2019 he disclosed that he’d been taking antidepressants. Lockdown, however, has been relatively kind to him. Each morning — at 5.30am on a good day, 6.10am on a bad day — he jogs around the Lambeth Palace garden, which, at the time we meet, is frilled with cherry blossom. He has enjoyed spending more time with his wife, Caroline. His health is “very good. It’s all under good control.”

We are meeting to discuss his book Reimagining Britain. It’s deep into Lent, and many Britons have decided that they have given up enough already this year. Welby is reduced to green tea, because he has given up coffee. “There’s nine days and about eight hours till I can have a coffee. ‘I’m fine,’ says he, lying through his teeth!”

On the radio, Welby can come across as flat. In person, he is sharp and witty. I stop trying to predict whether the next sentence out of his mouth will be spiritual or sarcastic.

First written in 2018, Reimagining Britain has been updated for plague times. Its focus is on what it means to love your neighbour: Welby calls for restoring the family as “the centre of policy”; a focus on community-based housing, rather than increasing home ownership; and decentralising power to avoid the effects of dehumanising bureaucracy. In its conclusion, there is fresh urgency: “The Church of England has trundled along, putting up with what everyone agreed was wrong but nobody could face. Time has run out.”

“Remember, we go back, the church in England, to 597,” he says. “There’s a sense that we’ll always be here. Inertia gets built into the whole culture of the thing. And part of that is good . . . But we need to change.”

As we speak, the world does not seem on course for wholesale change. At Goldman Sachs, junior bankers complained about working 95-hour weeks, only to be told to go “the extra mile” for clients. What does Welby, who sat on the UK’s parliamentary commission on banking standards, make of it?

“I’m thinking how frank I’m going to be.” He takes a breath. “I just think it’s plain wrong. Ninety-five-hour weeks — in certain circumstances, fine. We all have times when you have to work ridiculous hours in a real crisis. But when you look at their return on capital employed, when you look at the remuneration of the really senior people . . . The attitude that you don’t hire some more junior people, so that they can work still a long, heavy week — a 50/60-hour week — but have time for family, for dating, for fun and sport, [means that] you’re saying nothing matters more than the maximum amount of money we can get. You’ll carry that into ethics of the organisation.

“You can’t compartmentalise and say, I’m going to make you work a 95-hour week, because we’ve got to have more profit, but you’ve got to be really ethical while you’re doing that. Because what you’re asking them to do is not ethical. It’s internally incoherent . . . I really worry where I see staff working too hard.” He nods at an adviser, who mostly corroborates his alibi.

Welby’s political interventions do not always sit well with his flock. He voted Remain, they mainly voted Leave. He skewers the government, they skew Conservative. But for him, the Church is inherently political. His favourite predecessor as archbishop is William Temple (1942-44), who popularised the term “welfare state” and frequently clashed with Churchill’s government, even demanding to know the date of D-Day in case it fell on Palm Sunday.

In his book, Welby depicts Britain as a country that has become embarrassed by its Christian roots. Since 1983, the proportion of Britons affiliating with the Church of England has halved to one in five. In the US, 28 per cent of people say that the pandemic has strengthened their faith. In the UK, it’s just 10 per cent. Joe Biden mentioned God four times in his inauguration address, while in Britain the Trussell Trust, which supports more than 1,200 food banks, no longer talks about its church origins. The footballer Marcus Rashford has won the support of millions by calling for free school meals for children during lockdown, but who knows he has “God puts you on a path in life” tattooed on his chest? “Oh, it doesn’t surprise me at all,” says Welby.

Does it sadden him that people aren’t more open about their faith? “In some cases, it does. In one sense the pendulum has swung so far that you have to justify to people the idea that it’s remotely a good idea to do any work with you at all.”

But “in one sense it doesn’t matter because God sees, and that’s the key thing. I mean, we’re not Unilever — we don’t have to put the brand on every bit of product.” In most of the world, he emphasises, faith is still the default. “For over 80 per cent of the world’s population, the idea that someone is not to be trusted because they hold a faith is just bewildering. They just think that’s bizarre!”

As God has been pushed from public view, Britons have seemed to cast around for replacements: pets, yoga, the philosophy of Jordan Peterson. “He’s a really good writer. And a really good speaker. I think he’s fascinating,” remarks Welby. Are people trying to compensate for a God-shaped hole?

“I think there’s an anxiety caused by the fact that it’s very difficult to discern the rules and values [of society]. And in one sense I’m not really worried about that, because the rules and values were extremely hypocritical in many ways.”

Welby reads history voraciously; the Victorian period is his favourite. “Everyone knew what the rules were in late Victorian times, when they also had child prostitutes in London. Hypocrisy was devastating.”

The modern suspicion of the Church means that Welby has to fight for opportunities to be visible. Did he consider going to the London vigil for Sarah Everard, a young woman murdered in March? “To be honest, no, I didn’t. I should have thought about that. I’m slightly shocked [that I didn’t]. Sarah Everard, of course she’s a symbol, but she’s so much more than that: she’s a human being.” Welby’s good intentions are almost tangible; his battle to remain relevant is a daily one.

When coronavirus hit, the Church had no crisis-management system and hadn’t really thought of online worship. Many priests were furious at their churches being shut; some felt Welby was not present enough.

“I got quite a few things wrong at the beginning and I learnt quite quickly. I didn’t push hard enough to keep churches available for at least individual prayer in the first lockdown. We also said clergy couldn’t go in, and personally I feel I made a mistake with that . . . I can make all kinds of excuses. I still think I was too risk-averse.” When did he realise? “May. June. May.”

Hmm, he told angry General Synod members in July that he stood by the decision. The risk with playing politics is that you become a politician.

Still, he highlights successes, notably the surge in online worship. The Dean of Canterbury went viral after his morning prayer sessions were interrupted by his cats sipping his milk and disappearing into his cassock. “He gets letters from all over the world, whereas previously we had 20 people at half past seven in the morning,” enthuses Welby.

Can pets go to heaven? “I have never been asked that question before.” He pauses for reflection. “Given the fondness we have for our dog, our current dog and the previous one, I am quite prepared to believe that pets go to heaven.” (The Welbys’ dog, Bramble, is an excitable, “soft as you like” Clumber spaniel, who arrived at the time he became archbishop. His wife took the view that “everything [was] complete chaos . . . so why not make it a little worse by having a puppy?”)

The more immediate question is how the Church can encourage those newcomers who have watched services online to worship in person in church. “I hon-estly don’t know. I gen-uinely don’t have an answer. We’ve got to go on doing hybrid stuff.”

How the Church monetises online worship is another issue. With collection plates empty, English dioceses have racked up millions of pounds in deficits. Priests fear that some churches will never reopen. “It’s possible, but I doubt it,” says Welby, with the shrug of someone who has made peace with continual financial strains. Three-quarters of churches were expected to open over Easter, and many more should come alive over the summer. “There’s no plan to close them.”

The pandemic period also featured a reckoning over race. In the culture wars, Welby is ambiguous. His favourite novel is Rudyard Kipling’s Kim, and he lambasts cancel culture (“a parasite consuming the possibilities of liberty and justice”).

Yet before the Black Lives Matter protests, he said that the Church was “deeply institutionally racist”. With the retirement of John Sentamu as Archbishop of York last year, there is a lack of diversity in leadership roles. Welby has backed plans for more black clergy.

He has also said that the Church should rethink its depiction of Jesus as white. So what colour skin did Jesus have? “Middle Eastern. I’m terribly literal,” he laughs. “Dark-skinned, I would imagine, and not blue-eyed, blond-haired, Anglo-Saxon.”

When will there be an Archbishop of Canterbury from sub-Saharan Africa? “There’s no reason why there couldn’t be next time. I would love to see an archbishop from the global south. The nature of the job and the constitutional stuff means that it would take quite a lot of organisation, but it would be wonderful. Because 85 per cent of the communion is based in the global south. The average Anglican is a woman in sub-Saharan Africa in her thirties on less than $4 a day.”

Anglicanism’s global reach is its lifeboat. It’s also a liability. Many African bishops oppose gay rights — the head of the Church in Nigeria recently described homosexuality as a “virus”, leading to a rebuke from Welby. Meanwhile, many English clergy are ready for the Church, at least in England, to end its ban on same-sex marriage. Is it only a matter of time?

Here, the freethinking Welby evaporates. “I’m not going to avoid the question, but I’ll be quite open about the fact that I’m not going to answer it properly.” The Church is in a year-long process of deliberation. “I’m not going to say anything that prejudges where people come out.” His tone is so grave that I decide not to pick up on his choice of verb.

Some want him to show leadership. But for Welby, the most bitter arguments are to be reconciled, not won. It’s a principle he lives by. In a break for photos, he concedes that he isn’t watching the BBC drama Line of Duty: “I want to but the rest of the family don’t. So we’re watching Call My Agent!”

I try a simpler question: would he support allowing marriages in the open air? “Yes, of course I would . . . You can baptise people in the open and you can bury people in a churchyard. Why can’t you get married outside the church?” He throws his hands in the air. Is that exasperation? “The expression is ‘Why do people make all this so difficult?’” Which people? “Lawyers!”

Lawyers are also thwarting the Church’s efforts to promote social housing on its land: charities must maximise economic returns. “There are different opinions,” Welby says. “There are some opinions that the social and environmental aims of the organisation can play a role . . . I think bits of law that get in the way need to be sorted out. Yes, that is a deliberately provocative statement.”

Welby was recently forced to deny Meghan Markle’s suggestion that he had married her privately to Prince Harry before their televised ceremony. But his sympathy with the prince is clear. “It’s life without parole, isn’t it? If you go back to the 1930s, Edward VIII — he was still a celeb and followed everywhere once he’d abdicated. We expect them to be superhuman.”

Archbishops get parole and release. This summer, Welby goes on sabbatical — or, as his staff must call it, “study leave” — to write a book on reconciliation, drawing on his time in Nigeria, where he put his life at risk while trying to bring Muslims and Christians together in the early 2000s.

He will reach the compulsory retirement age of 70 in January 2026. Will he carry on until then? “All other things being equal, I would hope so.” He would become the longest-serving Archbishop of Canterbury since the 1970s.

So the job isn’t too exhausting? “It has its moments. Working one day a week can be quite demanding,” he jokes. “You know the old definition of a clergyman? Six days invisible and one day incomprehensible.”

Welby strikes me as neither. He is a rare mix of kindness and practicality. When I listen back to my recording of the interview, I hear how often he drops in the phrase “in one sense” — in one sense, it doesn’t matter if British people don’t talk about their faith; in one sense, the busyness of lockdown for him has been welcome. Welby is a patient man in an impatient era. But his self-deprecation cannot obscure an inner resolve.

People will react differently to the Church’s attempts to shape political priorities. Some will be unforgiving of its unwillingness to update the definition of marriage. All I can say is that, after the archbishop opened the vast wooden door of Lambeth Palace, I walked past the magnolia trees in the garden and felt unexpectedly moved. I said a prayer of thanks — partly out of tradition and partly out of hope.

Henry Mance is the FT’s chief features writer. Justin Welby’s “Reimagining Britain: Foundations for Hope” is published by Bloomsbury on April 15

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first.

Letters in response to this article:

Innovation can empower the church’s pew-dwelling faithful / From Jim Sanders, Burke, VA, US

Welby’s considered stance makes compulsive reading / From John Webster, London SW1, UK

Comments