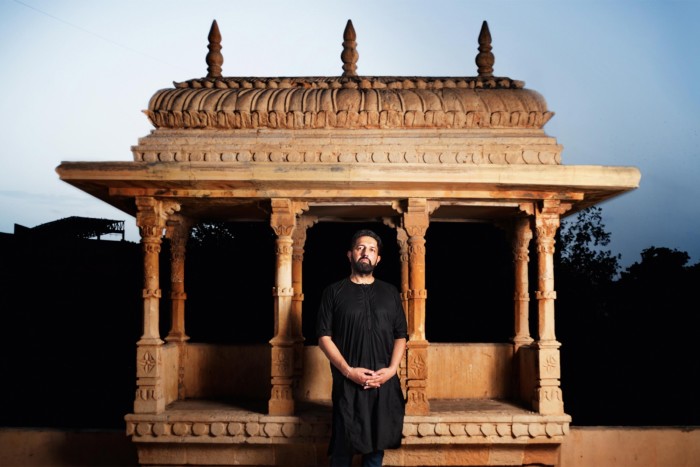

Artist Osman Yousefzada’s guide to Karachi

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

My connection to Karachi has been as part of the diaspora. I first travelled there with friends I’d met as a student at SOAS in London. I had grown up in a closed, patriarchal Pashtun community in Birmingham. By 15, I still hadn’t been into the centre of town. My parents had migrated from a very rural northern village close to the Afghan border, so these urban Karachiites really enriched my knowledge of Pakistani culture. The women were far freer, Sufi music was integral and the poetry of Ghalib and Faiz opened the door for me.

Karachi reminds me of Rio – it’s a living, breathing metropolis of some 20 million people, right on the Arabian sea, so there’s an ocean breeze and cool evenings. It’s a one-time provincial fishing village that became the capital after partition in 1947. It remains a port; it’s where my parents travelled to board a plane to London – my dad in the ’60s and my mum in the ’70s. To me, it’s much more cosmopolitan than any other place in Pakistan, full of entrepreneurial spirit. Its sheer scale and diversity means it is pretty progressive and welcoming; that’s perhaps also why it’s also seen as dangerous and a place of ethnic strife. Television shows such as Karachi Kops do little to abate that image.

Karachi is often called “the city of lights”, largely because of the vibrant nightlife of the ’60s and ’70s when there was a sophisticated cabaret and music scene. Since Muslims were banned from buying alcohol in 1977, the social life has shifted; now it’s much more focused on people’s homes. The best way in is to have a connection – mine was Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, an award-winning director who can throw a mean dinner party, and even let me hold her two Oscars. But I love going to restaurants too. One of my favourites is Okra in the commercial district, Zamzama. The food has a slightly Mediterranean flavour, which is more traditionally Pakistani at lunchtimes, and the owner, Ayaz Khan, has become a mentor to many young chefs in the city. Lots of expats go there – it’s a bit of a scene. They do a kick-ass bread-and-butter pudding.

I also go to Café Flo. It is a little taste of France in Karachi, with white linen tablecloths and a leafy outdoor terrace. It’s run by Florence Villiers, the daughter-in-law of popular singer Noor Jehan who was probably the Édith Piaf of Pakistan. I always order the tuna tartare – it’s amazing. For traditional Pakistani food I go to the Village Restaurant, one of the oldest in Karachi. They grill all the food in front of you, and everything is served on tin plates with elegant earthenware finger bowls. Burns Road, which was recently pedestrianised, is the street food mecca. Everywhere you look there are bun kabab coming out of ovens and skewered chickens being barbecued over open fire pits. Don’t miss Waheed Kabab House’s chapli kababs.

I usually stay at the Ambiance Hotel, a small, quiet place in a converted house in the centre of Clifton. I work from a studio space at Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture in a building that was earmarked for demolition but moved, brick by brick, to Clifton. It’s now a beacon of 19th-century colonial Karachi in a modern area. Then there’s TDF Ghar – a 1930s bungalow with a beautiful café and a rooftop with incredible city views. These sites are a throwback to a British colonial era when Victorian and Edwardian designers were in a game of architectural oneupmanship with the Mughals they had deposed. Also worth a visit for the architecture alone is NAPA, the National Academy of Performing Arts. It stages performances in what was once a Hindu gymkhana, a kind of sports and social club with stables and vast dining rooms.

There’s a thriving contemporary art scene spearheaded by women. Canvas Gallery, founded by Sameera Raja, is an airy, modernist space that champions artists such as Salman Toor, whose work explores the experience of queer brown people. At Koel, director Noorjehan Bilgrami blends art with craft in hand-block printed textiles and cushions. For interiors, I love architect turned furniture designer Zahra Ebrahim, who uses historic marquetry techniques to create the lighting and tableware on display in her Korangi showroom.

For people-watching as much as shopping, visit Zainab Market, a traditional craft bazaar where you can buy everything from Kashmiri carpets costing tens of thousands to trinkets for 10 rupees. There are hand-embroidered shawls, bedlinens and leather jackets – it’s a microcosm of Karachi, a place where ancient and modern culture collides.

Visit @artists_emergency to support Yousefzada’s Pakistan Flood fundraiser art sales. The Go-Between by Osman Yousefzada is published by Canongate at £14.99

Comments