‘Brexit dividend’ rule change prompts fears over data flow with EU

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Four years ago, UK businesses were scrambling to overhaul the way they collected workers’ personal information before sweeping new data protection rules came into force, in May 2018.

Now, business leaders wonder if they will have to rip up the rule books again — as a result of the British government’s plans for an independent, post-Brexit, data regime.

“Companies have paid the price of achieving GDPR [General Data Protection Regulation] compliance,” says Adam Rose, a partner at lawyers Mishcon de Reya. “If the government turns around and says you didn’t need to bother doing any of that, or will have to jump through new hoops, that’s going to annoy them.”

The volume of data produced globally is hard to comprehend. According to the World Economic Forum, the estimated number of bytes in the digital universe in 2020 was 40 times greater than the number of stars in the observable universe.

And although the creation and transfer of that data across the world can appear seamless, a complex architecture of rules and regulations govern what companies must do to keep it all safe and secure.

“If you asked most people, they would be surprised to know that information can’t flow freely around the world,” says Ross McKenzie, partner at lawyers Addleshaw Goddard. “But there are laws in the UK and Europe that limit companies from sharing data internationally.”

In the UK and the EU, the rules on GDPR govern the way data can be stored and transferred internationally. The UK, however, plans to water down its data protection rules and pursue agreements with non-EU countries — such as Australia and the US — in a mass overhaul of its data regime, post-Brexit.

UK culture secretary Oliver Dowden calls the plan a “Brexit dividend” for the economy. However, critics fear it could end the free flow of information between Britain and the EU — hurting businesses and citizens.

“Data is a huge part of UK plc’s value,” says Rose. “We are a stable place to do business with strong laws, good data centres, good data scientists. The UK is a major centre for data-based industry and there is a risk of diverging from our main trading partner, which is Europe.”

In a consultation unveiled in September, the UK government set out plans to roll back key elements of EU data protection regulation that it had put on its own statute book during Brexit.

Those plans include deleting or rewriting GDPR’s article 22, which guarantees human checks on decisions made by computer algorithms and, according to campaigners, provides a safeguard against machine bias.

Such moves put the UK on a collision course with the EU. The latter has warned that it will remove its data-sharing agreement with the UK if the privacy of its citizens is threatened.

The EU lets data flow freely from the EU to the UK as a result of a so-called adequacy decision. This means the European Commission has ruled that Britain adequately protects personal information and can be trusted with the data of its citizens.

But, if Brussels decided the UK no longer adhered to sufficient data standards, it could revoke the ruling, thus halting the free flow of information across the Channel.

“Every piece of legislation being looked at that creates significant divergence from the way things are done in the EU comes with the risk that it is harder to trade with the EU,” says James Mullock, partner at lawyers Bird & Bird.

“We have an adequacy decision that enables data to flow to the UK from Europe. Any divergence [in rules] potentially puts that adequacy decision at risk.”

To avoid falling foul of regulation, companies already have to carefully police the way they handle data.

“Because of Brexit, the UK has a completely separate approach” to data sharing, says McKenzie at Addleshaw Goddard. Multinational corporations with pan-European operations “have to deal with both the UK regulators and the European regulators. It’s a massive compliance burden.”

Businesses are, he adds, “screaming out for data protection lawyers and compliance specialists”.

In July 2020, a European ruling, prompted by an activist’s battle with Facebook, threw up a hurdle for businesses transferring data between the EU and the US. The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) removed an agreement, that companies relied upon to easily move data, because of concerns about surveillance by the US state.

Before the CJEU ruling, companies relied upon the so-called data protection shield to conduct transatlantic trade. Now, EU companies must conduct individual assessments of each data transfer to a non-EU country in order to ensure compliance.

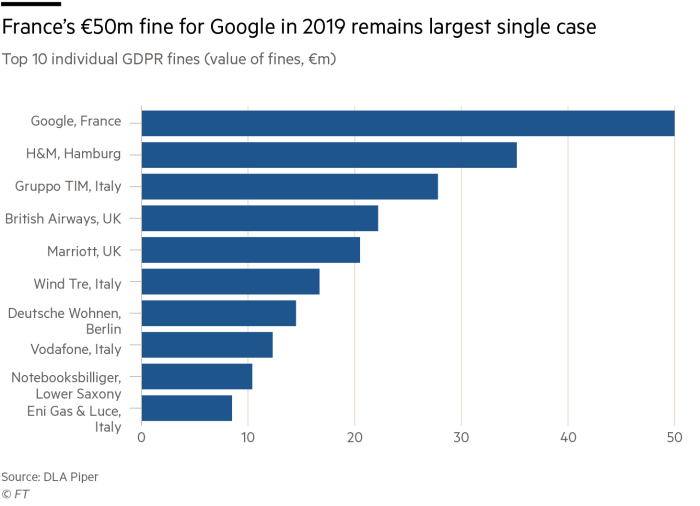

Any data breach now brings the risk of financial penalties for European companies, following the introduction of he GDPR rules and Brexit. Organisations can be liable for fines from the Information Commissioner’s Office in the UK and from regulators in Brussels.

UK-based businesses, meanwhile, have an even more complex landscape to negotiate, as a result of Brexit, adds Mullock. Companies fall under “two regulatory regimes”, he points out. With the fines that come with GDPR breaches, “that is a real concern and could create double jeopardy for businesses.”

Britain after Brexit newsletter

Keep up to date with the latest developments, post-Brexit, with original weekly insights from our public policy editor Peter Foster and senior FT writers. Sign up here.

Comments