Scientists shrug off failures in hunt for Alzheimer’s treatments

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

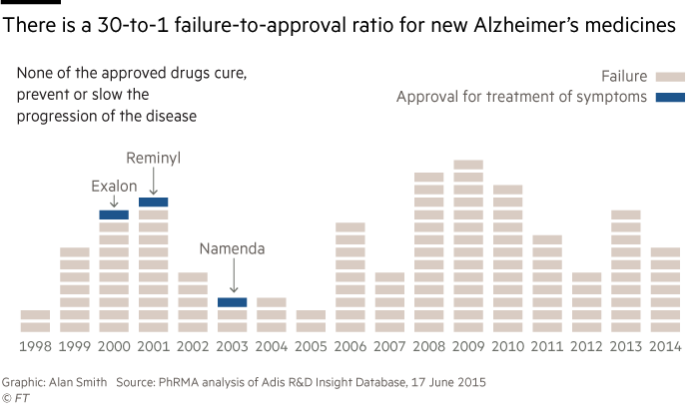

Even in the world of drug development, where the odds of discovering a new medicine are very low, the record of companies trying to find treatments for Alzheimer’s stands out as particularly abysmal.

There are just four drugs approved for the debilitating form of dementia, which is the focus of this year’s Financial Times seasonal appeal in support of Alzheimer’s Research UK, but all of them treat symptoms associated with the illness and do nothing to halt or slow its progress.

Most recently, Axovant, a New York biotech group, announced that its experimental medicine, Intepirdine, had failed a late-stage study, capping a 14-year losing streak for the pharma industry where no new drugs have been approved.

The failure of the trial, which was announced in September, was the latest in a long line of disappointments, with companies such as Merck, Eli Lilly and Lundbeck revealing negative data from large studies in the past 12 months.

Despite the high failure rate, drugmakers have persisted, attracted by the huge potential of tackling a disease that affects nearly 44m people worldwide.

Any company that were to find a disease-modifying drug would be richly rewarded for helping to reduce the high cost of caring for people with Alzheimer’s, which is expected to run to $259bn in the US alone this year — a figure that will only increase as the population ages.

“When someone is successful, Alzheimer’s will become very quickly the single largest therapeutic area in drug development,” predicts Ryan Watts, chief executive of Denali, a San Francisco company researching treatments.

The next big hope is a medicine called Aducanumab being developed by Biogen, a large Massachusetts-based biotech company, which is expected to announce results from two late-stage clinical trials in 2019 or 2020.

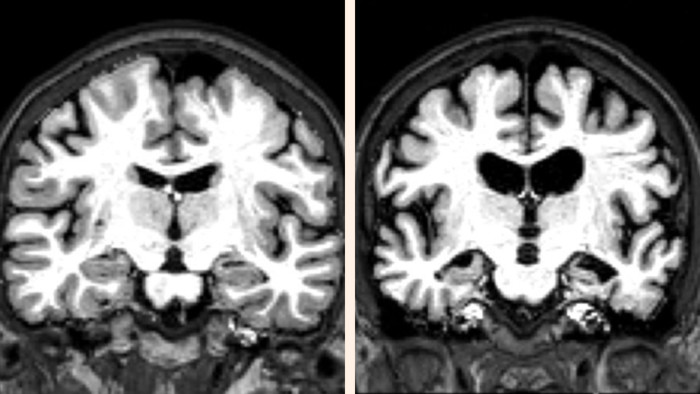

Aducanumab is designed to clear the brain of the sticky “amyloid beta” plaques that some scientists blame for the disease. Earlier trials show the medicine is able to remove the plaques, although there is less clear evidence of a corresponding reduction in the speed at which patients lose their brainpower.

There are also concerns about the medicine’s safety, with a significant proportion of patients experiencing potentially dangerous brain swelling at the highest and most effective dose.

The two Biogen trials, known as Engage and Emerge, are seen as a conclusive test of the “amyloid hypothesis”, which holds that the plaques cause Alzheimer’s and are not just a symptom.

Wall Street is sceptical about the drug’s chances, with a recent poll of investors by Mizuho, the investment bank, putting the odds of success at 45 per cent.

Part of the hesitancy stems from the failure last year of Eli Lilly’s medicine, Solanezumab, which also targeted amyloid, although Samantha Budd-Haeberlein, vice-president for Alzheimer’s discovery and development at Biogen, says her company’s attempt differs in several respects.

Unlike Biogen’s drug — which seems to be effective at removing amyloid — Lilly’s drug did not clear the plaques from the brain but tried to trap soluble forms of the substance in the blood, Ms Budd-Haeberlein points out.

The trials of Aducanumab have also enrolled people whose disease is less advanced than those participating in the Lilly study, including both patients with mild Alzheimer’s and those who are only just starting to show symptoms.

“We’re considerably earlier in the stage of the disease [than Lilly],” says Ms Budd-Haeberlein, adding that the company might eventually test the drug in patients who have brain plaques but who are not yet showing symptoms.

Some in the industry are concerned that if Biogen’s trial were to fail, it would deter further investment in the field.

“There is still a lot of interest in the disease — it’s one of great public importance — but I do believe there will be a diminution in investing unless we see some success,” says Steve Holcombe, chief executive of vTv Therapeutics, which is trialling an Alzheimer’s drug in a late-stage study.

“Patients need a win, caregivers need a win, and investors need a win,” he says. “Every time we get a failure, it takes that much more wind out of the industry’s sails.”

However, several biotech companies working on Alzheimer’s say they have found it relatively easy to raise capital in recent years, a sign that investors are willing to put money behind the disease despite the poor results so far.

Denali has raised $349m in two funding rounds, including $130m in August of last year, while Alector, also based in San Francisco, received a $205m payment last month as part of a partnership deal with AbbVie, a large pharmaceuticals group.

And Tony Coles, chief executive of Yumanity, raised $51m last year for his company, which is researching treatments targeting a process known as “protein misfolding” that has been implicated in Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative illnesses.

“The investability depends on your appetite for risk, but a small amount of money can go a long way and the returns can be significant,” says Mr Coles, adding that the company is considering raising more cash soon.

“We’ll seek to raise money opportunistically and this might be a good time,” he says.

Companies like Yumanity are benefiting from a belief that the field of Alzheimer’s is at an inflection point similar to the one that sparked a renaissance in cancer research about a decade ago.

“We are where oncology was 10 or 12 years ago, when most tumours were thought to be intractable and could only be treated with chemotherapy or radiation,” says Mr Holcombe.

The key to unlocking new cancer therapies was the realisation that it was not a single disease, but rather a multitude of conditions marked by different genetic traits. By dividing patients into ever smaller subsets, and then zoning in on the particular features of their individual cancers, drugmakers made big strides.

Executives say the same approach can now be applied to Alzheimer’s thanks to a better understanding of the genetics of the disease and new imaging technologies that can scan the brain for plaques and tangles known as “tau”.

“All of these new mutations that are risk factors have really come to light in the last five years through whole genome sequencing, and that’s how we select patients and targets,” says Mr Watts of Denali.

Tell us your story

Has someone in your family been affected by Alzheimer’s?

Tell us about your experience with the disease here.

Join Dementia Research

Anyone can help. Click here to find out how

Denali and Alector are developing drugs to encourage the body’s own immune system to tackle Alzheimer’s, much like immunotherapies have been used to fight cancer with considerable success.

However, some observers say the field of Alzheimer’s is still a large distance from the kind of “precision medicine” that is working so well in oncology.

With the exception of a couple of genes, including APOE4, which is strongly linked to Alzheimer’s, scientists have struggled to confirm other mutations implicated in the disease, whereas scores of genes have been associated with cancer.

“At this point in time we’ve not been able to meaningfully subgroup patients,” says Steve Paul, chief executive of Voyager, which is developing an experimental medicine for Alzheimer’s. “But maybe eventually we will.”

• Your gift will be doubled

If you donate to Alzheimer’s Research UK through the FT’s Seasonal Appeal, Goldman Sachs has generously agreed to match it up to a total of £300,000. Click here to donate now

The secret is to spot it early

By the time Alzheimer’s patients develop symptoms, they have probably had the illness for more than a decade. The term “mild Alzheimer’s” is now understood to be a misnomer because, by that stage, the disease is well advanced.

“We now recognise the disease has a long phase of up to 20 years before symptoms,” says Samantha Budd-Haeberlein of biotech group Biogen, adding there are efforts to develop a new “diagnostic framework” for the illness.

Drugmakers believe one of the keys to tackling the disease is to target it at an earlier stage, although doing so is fraught with difficulty, not least because it will be hard to identify asymptomatic patients.

Routinely scanning patients for brain plaques and tangles would be very expensive while genetic testing is not sufficiently advanced.

Even if doctors can identify patients at an earlier stage, it may be difficult to convince people who feel perfectly well to submit to a treatment programme like the one being developed by Biogen: patients on Aducanumab must visit an infusion centre every month to receive a large dose of a drug that has significant safety issues.

There are also fears that the methods for assessing Alzheimer’s, which mainly consist of questionnaires filled in by doctors, are not sensitive enough to detect changes in the earlier stages of the disease because they have been designed for more advanced patients.

One hope is that wearable devices such as smart watches might detect imperceptible changes that hint at Alzheimer’s long before there are any outward signs, although it will take years to validate these biological clues.

“The clinical endpoints we have are pretty crude today,” says Steve Paul of Voyager Therapeutics. “To the extent that we can digitise them or develop more sensitive biomarkers, it would be great — but I don’t see that as immediately on the horizon.”

Letter in response to this article:

Combination of drugs is key to halting Alzheimer’s / From Jeffrey Fessel, professor of Clinical Medicine, University of California

Comments