Patchy broadband leaves Europe with digital divide

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Skibbereen, a tiny town near the south coast of Ireland on the EU’s western front, was one of the first places in the country to be connected to a gigabit broadband network. The town, whose population is less than 3,000, was transformed into a digital “hub” in 2016 to bring faster connectivity to homes and businesses. Siro, a joint venture between UK telecoms company Vodafone and the Irish Electricity Supply Board, had kicked off a plan to light up 50 Irish towns with broadband speeds faster than those in most parts of London, never mind Dublin.

Skibbereen has proved a success, with many people relocating from Dublin to take advantage of the faster speeds. Siro has now connected 185,000 homes across the country, but a wider plan for faster broadband in Ireland, which relied on EU funds via the European Investment Bank, has been thrown into doubt.

A botched bidding process led to the exit this year of companies including Eir, the incumbent, and the consortium led by Vodafone. Energy company SSE also walked away from the Enet consortium, the only remaining bidder, as companies questioned the viability of the long-term plan. For the unlucky ones outside the original Siro footprint, there is still, therefore, a digital divide.

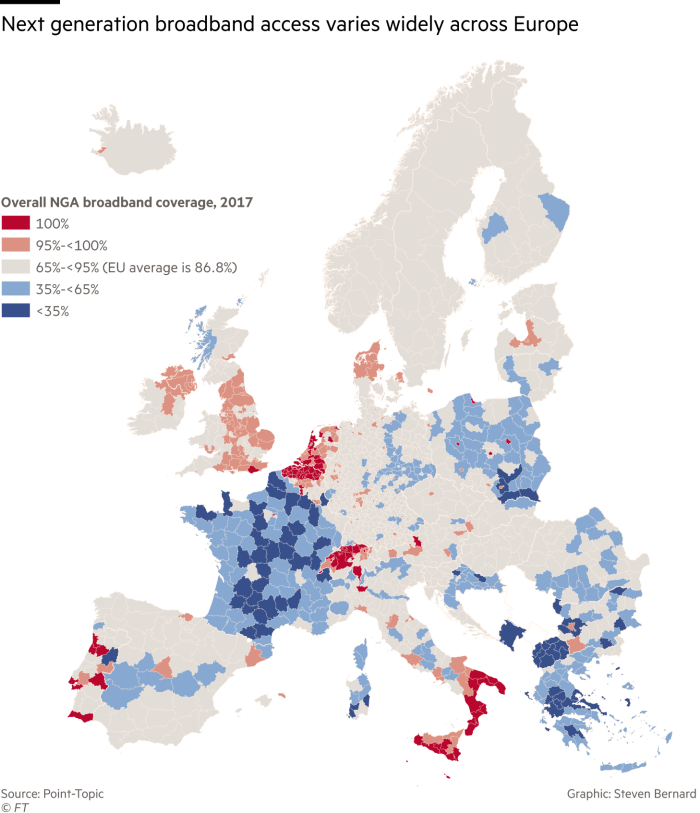

This kind of fragmented approach to fibre build has created a patchwork quilt of broadband networks, not just in Ireland but across the continent. Some rural areas that have received investment from telecoms companies enjoy ultrafast speeds, while nearby “second cities” will be surfing via copper phone lines, rather than next-generation access (NGA) — or faster, upgraded networks — for the foreseeable future.

The connected economy, with fast internet connections for all, has been something the European Commission has gone to great lengths to extol. Eight years ago it set a target for every household in the EU to be able to access a 30Mbps broadband connection — labelled “superfast” — by 2020. Superfast speeds enable multiple users in a household to use the internet at the same time — to download movies or stream music, say — with no service degradation.

Another Commission target was that half of all citizens were expected to take up an ultrafast connection, broadly defined as a gigabit line like those in Skibbereen, by that date.

Yet this June, the European Court of Auditors called time on those targets. The body said that while there had been significant progress in delivering basic connections, the higher ambitions would be missed.

The number of homes that could connect to a standard internet connection across the EU actually fell in 2017, according to the latest industry data. The 0.2-percentage-point drop from 2016 was an anomaly as it reflected the fact that more houses were built than internet lines connected, but it nonetheless revealed the challenge that policymakers have to overcome to deliver the dream of universal coverage.

Rural areas were shown to be dragging down the push toward superfast speeds. Patchy speeds in the countryside meant only 14 of the 28 EU member states had surpassed 50 per cent superfast broadband coverage in Europe.

The EU’s own report into the state of broadband highlighted that by 2016, huge swaths of rural France, Scotland, Greece, eastern Germany and Poland were still nowhere near hitting the 30Mbps standard. As for ultrafast coverage, only 15 per cent of homes in the bloc were paying for such a service by the middle of 2017.

Rural areas are not the only ones suffering from the digital divide. A Financial Times investigation published in July showed that some inner districts of Britain’s biggest cities suffer terrible broadband speeds too. Politicians also love to remind people that Brussels, the administrative home of the EU, was one of the last places in Europe to get a 4G network.

Iliana Ivanova, the member of the European Court of Auditors responsible for the report, argued that a sense of realism was necessary in the digital sector. “It is important that the EU sets itself challenging and realistic targets for broadband in the future — and meets them,” she said.

The auditor’s report, which was based on visits to Ireland, Germany, Hungary, Poland and Italy, said broadband policies were inconsistent and not all the countries had the right legal and regulatory conditions in place to attract competition, a key driver for investment. Financing is also a key hurdle. The European Commission estimates €250bn is required to hit the 2020 targets it initially set. Half of this would be needed for rural areas.

Some 95 per cent of Europe’s broadband upgrade is expected to be funded by the private sector, but companies say the European Commission has missed opportunities to stimulate investment.

The Electronic Communications Code, legislation passed this year but still being drawn up for implementation, was initially welcomed by the telecoms sector. To encourage spending on fibre and 5G networks it looked initially to ease regulations on telecoms companies, but later new onerous regulatory measures, such as a crackdown on telecoms “oligopolies” and new caps on international calling tariffs, were added, damping the code’s impact.

Some funding mechanisms are available, including the Connecting Europe Facility, a €24bn fund for investments in transport, energy and digital infrastructure, but telecoms companies say those are not being fully used. According to multiple sources in the telecoms industry, this is because it is difficult to convince shareholders to invest in rural areas where the payback is uncertain, even with the stimulus.

Funders have been willing to come into some markets, such as Italy and the UK, where the incumbent telecoms companies have been slow to invest in full fibre. That is the result of both political support and regulatory moves to champion smaller players, or altnets, by loosening rules to encourage investment.

Others argue that a different model is needed. Joao Sousa, head of the infrastructure and technology practice at telecoms consultancy Delta Partners, says governments should move away from using public subsidies in rural areas and instead encourage carriers to buy capacity from a single “netco” to ensure it is viable.

Co-investment in new networks can be a way for competing networks to reduce costs and ensure investments are viable in sparsely populated areas. The notion of a single netco — a designated supplier that would have a monopoly in a certain area but with strict wholesale requirements — has become a talking point in the sector.

“Regulators need to promote network sharing and release the 20MHz-30MHz low band of spectrum to increase coverage and speeds if rural broadband is to become anything close to a reality,” said Sousa. “Network sharing and low band spectrum availability are key to making rural broadband a reality.”

Telecoms companies and their investors remain wary of committing to full fibre in many of Europe’s biggest countries. With the European Commission preparing its political agenda for 2019, there is a sense of déjà vu. Policymakers still have to decide if they want European telecoms champions capable of investing rapidly in new networks or whether they should prioritise low consumer prices and competitive markets. In a year of transition for Europe, the onus could be back on local regulators and politicians to work it out.

Comments