Yuki Kihara: ‘I want to reclaim our place as an indigenous, third-gender community’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In a Samoan TV studio, a talk-show panel is discussing Paul Gauguin. Amid “oohs” and “aahs”, and talk of oestrogen pills, they peer closely at a copy of “Two Tahitian Women” (1899), set up on an easel. One leans forward: “As pretty as we are as Fa’afafine . . . Gauguin wanted us to be born with breasts while still having tipo,” she declares. “Tipo?” queries the host. “Penis,” she explains. “I think that’s what he wanted. He’s in love with the tipo.”

Yuki Kihara, the Japanese-Samoan artist representing New Zealand in the Venice Biennale, has turned her queer Pasifika gaze on the famous French artist.

Working with members of her Samoan Fa’afafine (third gender) community who know little of Gauguin, she has produced a five-episode talk show that is by turns hilarious and serious. Two weeks before the Biennale opens, organised and energetic at 7am New Zealand time, she plays me a snippet on Zoom, eager, I think, to see my reaction. Was it scripted? “The cast are like that on — and offstage,” she says. “I just turn the camera on them and off they go.”

In Venice, “First Impressions: Paul Gauguin” will be one part of the New Zealand pavilion’s Paradise Camp exhibition, where it will complement Kihara’s spectacular photography and her personal research archive of rare 19th-century books, posters and pamphlets. The centrepiece is a suite of 12 tableau photographs, directed by Kihara and shot on location in Samoa, in March 2020, on the eve of the pandemic.

These meticulously composed, super-luscious images are reworkings of specific Gauguin paintings, once again starring Kihara’s Samoan Fa’afafine community. Among the most poignant for being the most personal is “Nafea e te fa’aipoipo? When will you marry (After Gauguin)” 2020, which alludes to the problems of finding lasting love as a Fa’afafine. “We girls gossip about finding Prince Charming,” Kihara says, only half-joking. “I feel we all deserve to be loved for the whole person that we are.”

Yet I puzzle over the Samoan connection. In the 1890s, Gauguin left Europe for Tahiti, and later the Marquesas. He didn’t go near Samoa. His androgynous figures, surely, are Mahu, the Tahitian equivalent of Fa’afafine? Not entirely, Kihara says. Many of Gauguin’s people and landscapes looked to her Samoan. She thought she knew why.

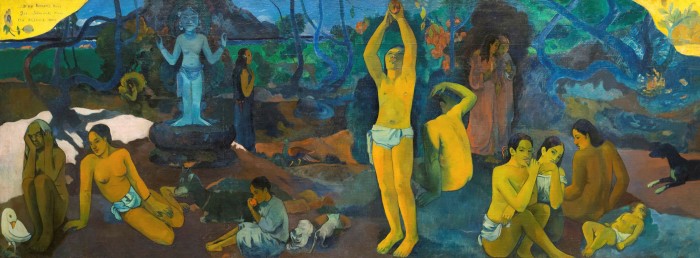

Gauguin returned briefly to Europe in 1893, then on his way back to French Polynesia two years later he spent time in Auckland, New Zealand, signing in (Kihara has found) at both the city’s art gallery and museum, where he would have seen images made in Samoa by the 19th-century photographer Thomas Andrew. In Paradise Camp the artist matches details of Gauguin paintings to their 19th-century sources and includes her own montage — “Three Tahiti(Samo)ans (After Gauguin)”, 2018/2020 — to highlight Gauguin’s apparent incorporation of a back view of a tattooed figure shot by Andrew into his 1899 painting “Three Tahitians”.

“Yuki’s rigour on the research side is compelling,” says Natalie King, curator of the New Zealand pavilion. “But there is also this side to her work that is utterly camp, flamboyant and dazzling. Artists usually swing between the two: Yuki has the capacity to meld them.”

Born in 1975 to a Japanese father and a Samoan mother, Kihara moved between Samoa, Japan, Indonesia and New Zealand during her childhood and teens, settling for a time in Wellington, where she studied fashion (her parents wouldn’t let her go to art school), then worked as a freelance costume designer and fashion editor. Times were tough in the 1990s, she says, as she transitioned to living as a trans woman. It didn’t help that her only form of ID was a Samoan passport, which pigeonholed her as “male”. But little by little she was transitioning to become an artist as well.

“I was so fed up, I decided that I was going to use my art to foreground my identity.” One upshot was “Fa’afafine: in the manner of a woman”, a series of sepia-toned self-portraits that rework late 19th-century postcards of Samoan people taken by western photographers.

The series arrived in New York in 2008 as part of the Met’s Living Photographs and paved the way for her first proper encounter with Gauguin. Beyond the museum’s own collection of Gauguins, she found reproductions of “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?” (1897-98). The androgynous central figure intrigued her, and so too did some of the poses in the painting, which reminded her of Manet’s “Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe”. Kihara was hooked: the artistic and research project that has occupied her for more than a decade began to take root.

“It was then I had the epiphany to look at Gauguin’s work with a critical eye to see what other similarities I could find,” she tells King in the catalogue. “Sure enough, I was able to uncover both direct and indirect links between Gauguin and Samoa that have never been seen before.”

With Paradise Camp Kihara delves into colonial history, gender politics and environmental concerns. In bringing together the two words of the title, she wants us to note the power of the “Pacific paradise” myth, so beloved of the tourism industry, to mask and marginalise: newly-weds stroll on the beach, some Samoans may serve cocktails, but the Fa’afafine community is not there at all.

“The idea of paradise that’s fed to us is so heteronormative,” Kihara says. “I wanted to challenge that by deploying the camp aesthetic.” For this, she draws on Susan Sontag, who defined “camp” as “playful”, “exaggerated” and embodying “the spirit of extravagance”.

Kihara talks of “upcycling” Gauguin’s work — by which she means “doing something original to improve it”. “There is a direct social and political intent behind what I’m doing: it’s to take the power back from western canonical art history, to reclaim our place as an indigenous, third-gender community in the Pacific, who have been neglected not just socially, politically, culturally — but environmentally as well.”

What happens to Gauguin? Rather than eclipse him, the process may enrich him, I suggest. “If it does that that’s great, but the primary audience for Paradise Camp is the Fa’afafine community. I want to use it to build Fa’afafine capital.” She smiles. “Maybe I’m just using him as a catalyst to get what I want.”

Comments