Six charts that lay bare what went wrong for Woodford

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Neil Woodford went from “the man who can’t stop making money” to unleashing Europe’s biggest fund management scandal for a decade. Just over five years after overseeing Britain’s most successful investment company launch, his business is in tatters and will close its doors in the coming weeks.

What went wrong for the UK’s best-known stockpicker? Thousands of column inches have been dedicated to dissecting the reasons behind Mr Woodford’s spectacular downfall since his flagship Equity Income fund was suspended in June. But for the first time a detailed data-driven analysis has revealed Mr Woodford’s changes in style and stock-selection behaviour that led to Equity Income’s collapse.

Stockopedia, the investment information provider, has crunched the numbers on Mr Woodford’s portfolio decision-making over the past five years. FTfm presents a selection of charts that tell the story of one of the fund industry’s biggest implosions.

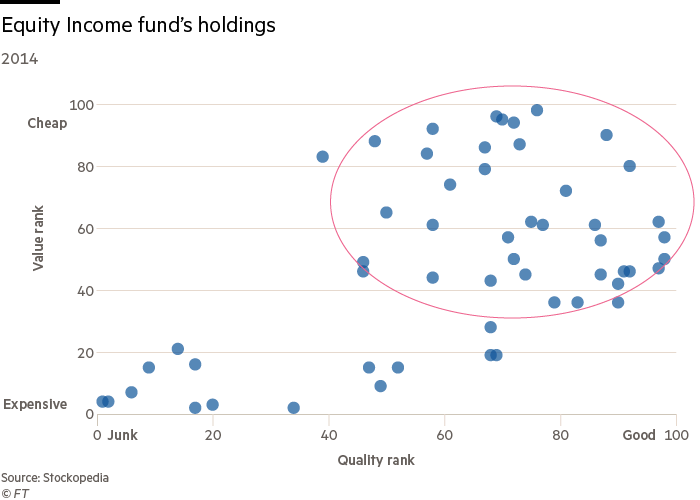

Chart 1: Early commitment to quality and value

When Woodford Investment Management launched Equity Income in 2014, it was described internally as a “widows and orphans” fund — a product ordinary savers could invest in and sleep soundly at night, knowing their capital would be protected.

Mr Woodford built the portfolio accordingly. Under Stockopedia’s definitions, the vast majority of the holdings were cheap and of good quality. The largest 20 were dominated by FTSE 100 companies — the types of businesses on which Mr Woodford built his reputation at Invesco. A third of the fund was invested in the top five stocks: AstraZeneca (8.3 per cent), GlaxoSmithKline (7.1 per cent), British American Tobacco (6.2 per cent), BT (6 per cent) and Imperial Tobacco (5.3 per cent).

Chart 2: Move towards speculative stocks

Within a couple of years Equity Income’s make-up had changed dramatically. Mr Woodford appeared seduced by an increasing number of early-stage healthcare, technology and financial stocks. Going by Stockopedia’s rankings, this meant a large proportion of the holdings were classed as expensive and of poorer quality.

While the fund’s top five holdings were still blue-chips, several speculative companies made up the top 10. These included Prothena, a Nasdaq-listed biotech company, Allied Minds, a US intellectual property commercialisation business, Theravance Biopharma, a medicines maker, and Benevolent AI, an artificial intelligence company. Mr Woodford had clearly been influenced by the performance of a handful of small-cap companies, including Prothena, which returned 249 per cent in 2015 alone.

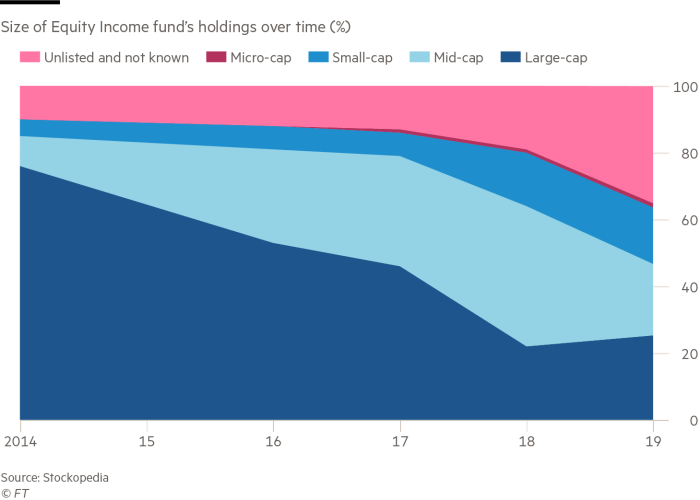

Chart 3: Small and unlisted companies start to dominate

When Equity Income launched more than three-quarters of the fund was invested in companies valued at more than £2.5bn, with less than 5 per cent in listed companies worth between £50m and £350m. Unlisted holdings and companies on which Stockopedia did not have any data were less than 10 per cent.

But over time this weighting changed dramatically. Large-caps dropped to a quarter of the portfolio, while unlisted and small-caps accounted for more than half. The switch started in 2017 when Mr Woodford faced a tide of outflows. To pay back fleeing investors, he was forced to sell the more liquid larger holdings, leaving an increasing rump of smaller and unlisted companies.

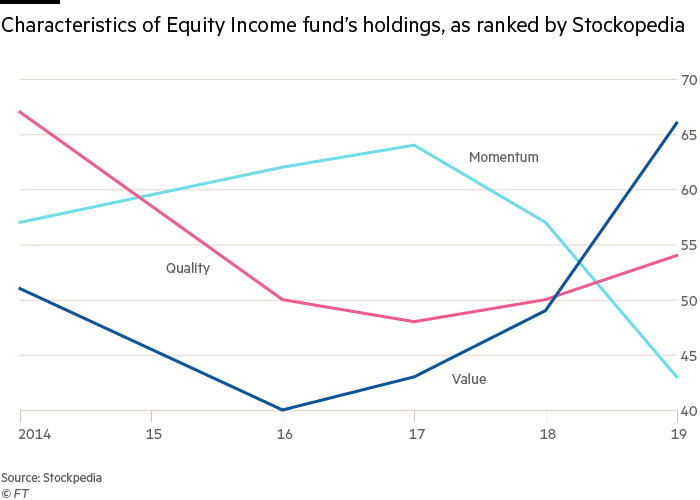

Chart 4: Investment style drifts

Throughout his quarter of a century at Invesco, Mr Woodford established a reputation as a contrarian investor who took big bets on large unloved companies, and made big calls on the direction of the economy. His style was understood and easy for financial advisers to explain to their clients.

But as Stockopedia’s categorisation of his fund’s holdings shows, his style fluctuated massively throughout his five years managing money solo. What began as a portfolio focused on large, quality companies, gradually switched to a fund with a heavy weighting to stocks more reliant on market trends. By the end, stocks defined as being undervalued dominated the fund.

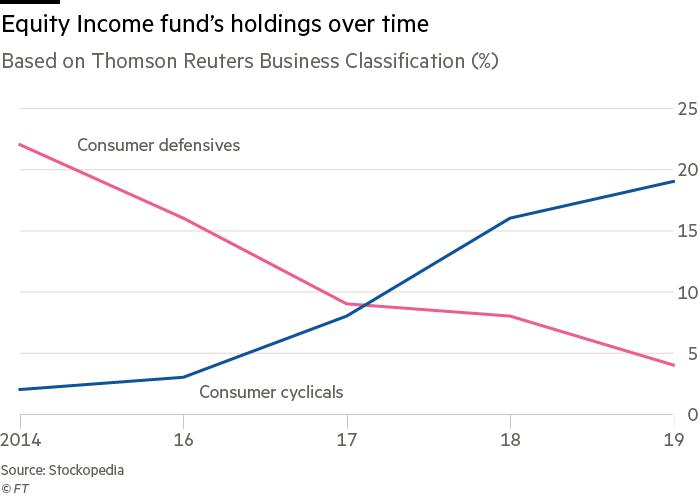

Chart 5: Stock selection changes

Mr Woodford was known for his commitment to unfancied stocks, such as tobacco companies, and other makers of consumer products that provide consistent dividends regardless of the economy’s health — known as consumer defensives. Mr Woodford duly loaded Equity Income up with these holdings, which accounted for 22 per cent of the portfolio at launch, compared with 15 per cent of the FTSE All Share.

But by 2019 consumer defensives had been replaced by consumer cyclicals, which represented 19 per cent of the fund compared with 11 per cent of the FTSE All Share. These companies, including housebuilders, are highly correlated with the domestic business cycle, which has been strangled by Brexit uncertainty.

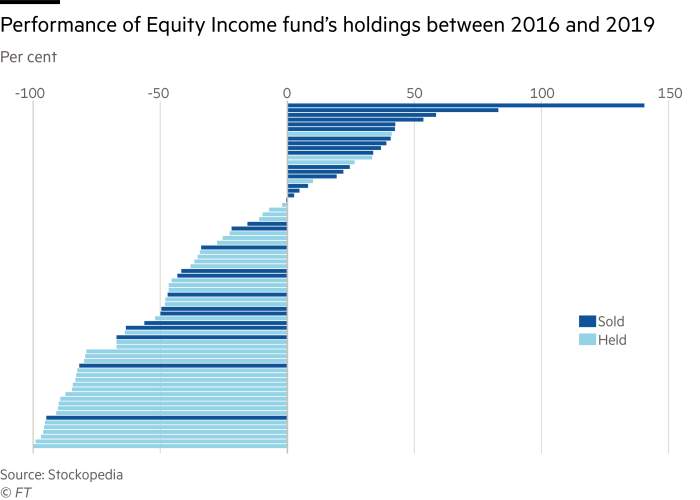

Chart 6: Winners were sold, but losers kept

Having produced strong performance for its first two years, Equity Income began to trail its benchmark and peers significantly from 2017 onwards. In 2018 it lost 17.1 per cent and is down 22.8 per cent this year. Chronic underperformance was a result of Mr Woodford being forced to sell his best-performing companies to meet redemption requests, while holding on to underperforming hard-to-sell stocks.

Stockopedia’s analysis shows that the vast majority of the companies Mr Woodford hung on to between 2016 and 2019 underperformed, while almost all of those he sold produced healthy returns. Over that period, 51 per cent of FTSE All Share companies produced positive returns, compared with just 27 per cent of Mr Woodford’s holdings.

Active, pragmatic approach was trumpeted

Neil Woodford’s company did not try to conceal his style shift. In fact, as far back as September 2016, Woodford Investment Management trumpeted his active, pragmatic approach.

“With a flexible investment mandate, it isn’t unusual for Neil to evolve his portfolios over time, as the valuation opportunity set constantly changes,” the company wrote in a blog post at the time when it discussed the sale of several large companies.

The topic of Mr Woodford’s shifting portfolio frequently came up in client meetings, with the company arguing that the divergence was positive.

But commentators have drawn parallels between Mr Woodford’s change in strategy to other well-known investment managers who altered course. These include Anthony Bolton of Fidelity International, who after a glittering career specialising in UK stocks switched to China, where investors in his fund suffered heavy early losses. He retired after just three years of launching the fund.

“Rather like a successful sportsman who chances his arm at a different sport and fails, Neil Woodford’s adventure into the world of private companies and small companies was much more likely to fail than succeed,” writes Tim Steer, a former fund manager, in his updated book The Signs Were There, which features a chapter on the collapse of Equity Income. “He was just not experienced enough.”

Comments