Italy’s bridge disaster: an inquest into privatisation

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In July 2013, on a motorway viaduct near Naples, a coach carrying 50 passengers smashed through a guard rail, plunging 30m over a precipice and killing 40 of those on board.

As with the Morandi bridge in Genoa, which collapsed last month leaving 43 dead, the Acqualonga viaduct was run by Autostrade per l‘Italia, the country’s biggest motorway operator. Prosecutors, alleging that bolts anchoring the guard rail were corroded, brought criminal charges against Autostrade personnel in 2015, including chief executive Giovanni Castellucci.

A judgment is due in the trial in December, although appeals could drag on for years. The company denies the charges. “For five years we have called for investment in maintenance, but instead there are more dead,” says Maria Loffredo, who lost her mother in the Naples accident. “It’s as if my mother died in vain.”

In the wake of the Genoa disaster, the company is facing many of the same criticisms. Even before an official inquiry has been concluded, some politicians have blamed the bridge collapse on a lack of maintenance. The furore could potentially lead to the renationalisation of parts of Italy’s motorway network.

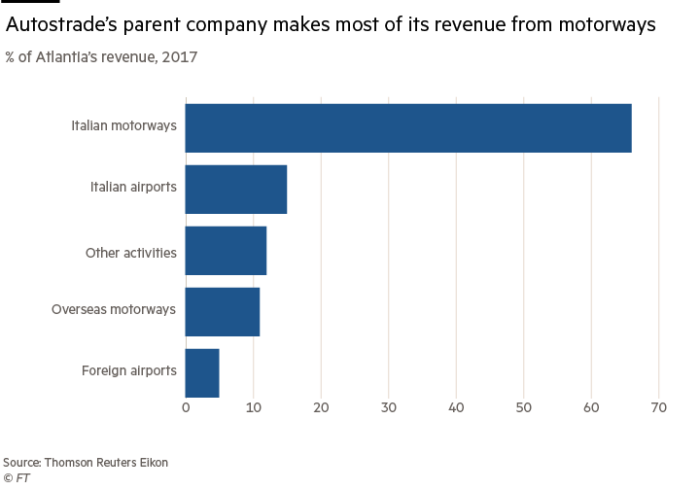

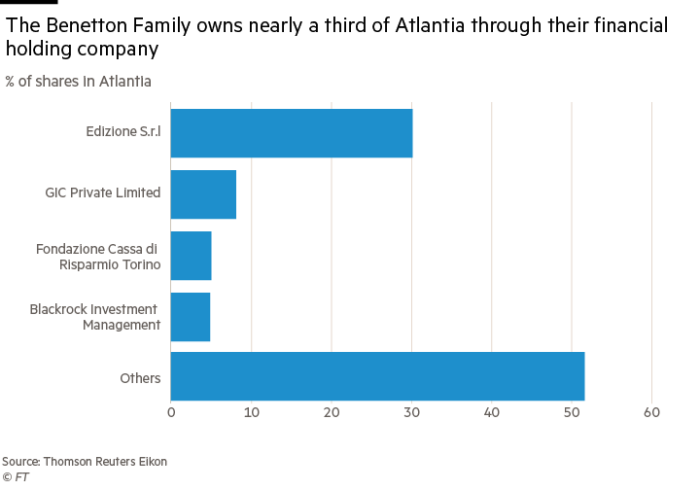

Privatised in 1999, Autostrade operates 51 per cent of Italy’s road network and is controlled by one of the country’s biggest private holding companies, Edizione, which is owned by the Benetton family. It holds a 30.25 per cent stake in Atlantia, Autostrade’s parent. That has made it the focus of the country’s punitive political mood, one that mixes demands for social justice with complaints about years of economic mediocrity and mismanagement.

The anti-establishment Five Star Movement, which is now the biggest party in the new populist government in Rome, has used the accident to step up its criticism of crony capitalism in Italy, where the state has, in its view, gifted sweetheart deals on public services to large private companies.

Luigi Di Maio, deputy prime minister and Five Star leader, has said nationalising Autostrade’s toll motorways was the “only solution”. The government has begun legal proceedings to revoke Autostrade’s licence.

“It’s a racket”, wrote Beppe Grillo, the comedian and founder of Five Star on his blog. “The motorways must be free. We haven’t paid taxes for years to make Benetton and co rich.”

As well as attacking big business, Five Star has also used the bridge collapse to go after the traditional political establishment for its role promoting privatisation in the 1990s.

This has made the Genoa disaster a pivotal moment for Italy that will be closely watched across Europe. It is one of the first important tests of the populist government’s ability to translate its fiery rhetoric into complex public policy. But it has also brought about a confrontation between the free market ideas that dominated the 1990s and the anti-elite sentiment that has become so prominent in western politics.

“They have found a golden seam of scapegoats: business, the old political class and a wealthy family of progressive politics. Everything chimes,” says Giovanni Orsina, professor of political history at Luiss University.

Autostrade finds itself playing defence on a number of fronts. The government had given the company until Tuesday September 4 to show that it had met its maintenance obligations in Genoa. Autostrade said on Friday it had “prepared counterarguments” and that it “has promptly fulfilled the concession obligations”. It would respond before the deadline, it said in a statement. The Ministry of Transport said on Monday that they had not yet received a response.

The publication last week of some of the details of Autostrade’s roads concession has further increased the scrutiny on the company.

“The concessions were an enormous gift,” says Giorgio Ragazzi, author of Lords of the Motorway and a retired professor of economic science at Bergamo University. “The motorists don’t realise, they just pay and go through, but the concessionaires have made enormous profits, which they haven’t reinvested in the sector.”

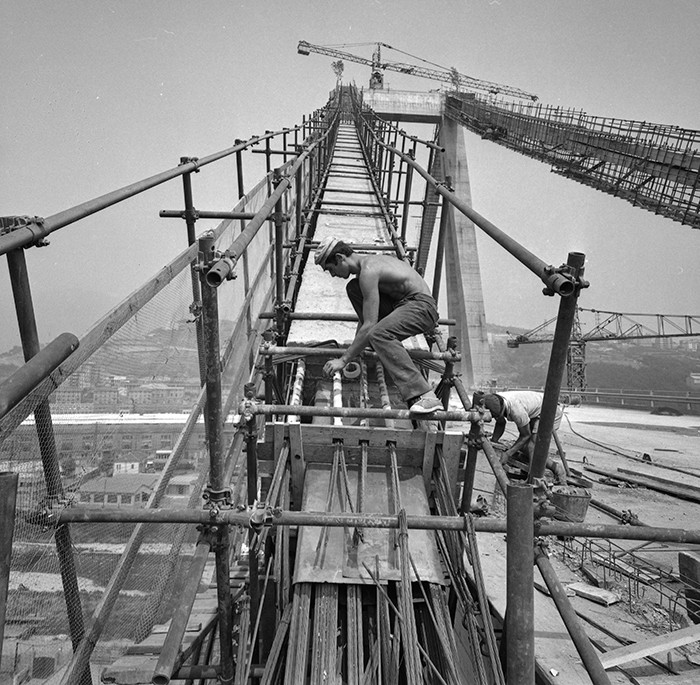

The controversy dates back to the 1990s, when the government began to dismantle the huge state-owned industrial complex that was built up after the war. At the time, almost 20 per cent of the total workforce was employed by the state, in industries ranging from chemicals to aviation and oil. “We have a saying — ‘the state shouldn’t make panettone’”, says Marcello Sorgi, a well-known political commentator at La Stampa newspaper who said privatisation was necessary at the time.

The Benetton-led group was the only qualifying bid for Autostrade after a rival consortium, led by Australia’s Macquarie Bank, failed to find enough financial support and applied only for a 10 per cent stake.

Entrusting Autostrade, a state agency with the licence to operate motorways, to a group whose main shareholder was best known for colourful T-shirts, was not as surprising a decision as it may now sound, according to Andrea Colli, professor of business history at Bocconi University.

Large investment funds did not exist in Italy and it was politically unpopular to sell to a foreign company, so the state turned to private entrepreneurs, offering favourable terms to extract the maximum possible capital from the sale.

“It was seen as better to have entrepreneurs with a proven record than speculators,” says Mr Colli, who has written a history of Edizione. “They represented the new face of Italy: industrial, entrepreneurial, and able to make things work.”

The four Benetton siblings had started out selling colourful knitwear in Treviso in 1965, but as the textile market became more competitive, they diversified. After unsuccessful forays into financial services, sportswear and skis, the family moved into infrastructure.

In 1990 it bought motorway catering company Autogrill, an experience which taught the group the value of long concessions, says Mr Colli. Textiles now account for just 5 per of Edizione’s €12.5bn investment portfolio, half of which is made up by transport infrastructure. In March, it agreed to buy Spanish group Abertis in a deal which would make it the biggest operator of toll roads in the world on completion.

Critics say that the contract to run the motorways appears highly advantageous to the winning bidder. Autostrade’s owners inherited a natural monopoly with the right to charge tolls until 2038, raising tariffs annually in exchange for maintenance and building new roads.

Between 1999 and 2016 tariffs rose 72.9 per cent on average, almost twice the rate of inflation during the same period of 37.4 per cent, according to a report compiled by Andrea Cioffi, a Five Star senator. In 2014 for example, the rate of inflation was 0.2 per cent but tariffs increased by 4.43 per cent.

Between 2006 and 2017 Autostrade invested €2.9bn in road maintenance, equivalent to about €300m a year, or 2.8 per cent more than was mandated in their contract . That compares to pre-tax profits last year of €1.4bn.

According to Mr Ragazzi: “We now have very high tolls and a very old and inadequate motorway system.” He equates the tolls to a tax, “which it would be better to pay to the state, not to concessionaires who have hardly invested anything”.

Autostrade was even allowed to subcontract, without tender, up to 40 per cent of maintenance work, to its own construction company, Pavimental. These included repairs on the Morandi bridge, according to Stefano Marigliani, head of Autostrade operations in Genoa.

An agreement signed in 2007 prevents the government from revoking the licence without severe financial penalty. Even if Autostrade failed to meet its safety and maintenance obligations, the state would still be obliged to reimburse the profits that could be expected until the end of the concession.

Ugo Arrigo, a professor of public finance at Bicocca University in Milan, says the clause is “absurd”: “It’s as if the captain of the Costa Concordia [the cruise ship which was wrecked off Italy in 2012] had been sacked for killing 30 people but then was allowed to keep his salary and pension for the rest of his life.”

Autostrade said that the EU analysed the concession earlier this year, including tariffs and rates of return, and concluded it was “adequate and in line with the European Union legal framework”. The company said it had invested more in the network than when it was publicly-owned: an average of €290m a year versus €266m. Mr Castellucci, the chief executive, told La Repubblica newspaper last week that the privatised company performed “radically better” in terms of investment and safety than the motorways which are still managed by the state.

Tolls increased because the state wanted to equip the network to deal with more traffic, he said, and were lower than other countries.

Others say the new government has exaggerated the problems. The coalition has been keen to label the state’s relationship with the Benettons and Autostrade “as a kind of Spectre [the James Bond film] with political and economic forces exchanging favours, interests and money”, says Mr Sorgi, “but the governments have often been more inept than malevolent”.

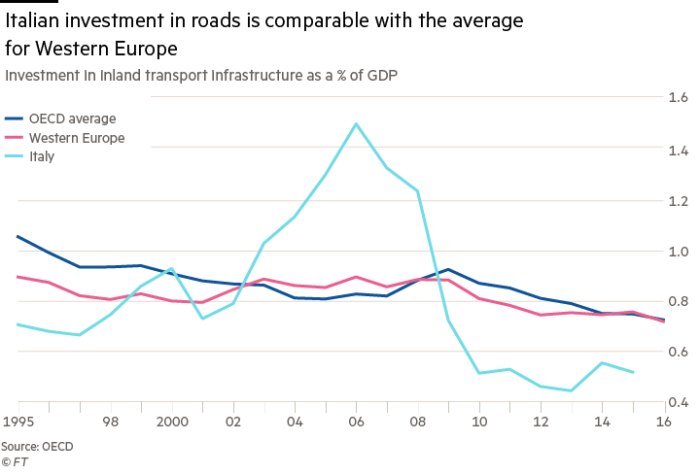

Road privatisation in Italy can claim successes. Motorways are arguably safer, with annual road deaths dropping from 420 in 1999 to 119 today. Italy’s state-run roads are in far worse condition than the motorways, with considerably less investment per km, according to Mr Ragazzi. OECD figures suggest Italy’s long-term investment in transport infrastructure is comparable with other western countries.

Five Star, however, had been critical of Autostrade well before the Genoa disaster. Mr Cioffi filed a complaint last year to the national anti-corruption authority saying it was “in the public interest” to break the contract with Autostrade. He blames Italy’s “amoral familism” for what he sees as the generous contract.

“There has always been a tendency to favour big companies, backed by pressure groups”, he says. “Italy in the 1990s was like Yeltsin’s Russia when public companies were given to the oligarchs. Everyone was looking out for their friends, rather than the public interest.”

Michele dell’ Orco, undersecretary at the Ministry of Transport and a Five Star legislator, says the government was not proposing full nationalisation but a gradual takeover of parts of the network where Autostrade had been “demonstrably inadequate”, including in Acqualonga and Genoa. “Considering the death tolls, the state could hardly do worse,” he says. Shares in Atlantia are down 28 per cent since the accident, given the threat to its biggest business.

But there are clear economic and political hurdles to nationalisation. The cost will add to the already high level of public debt and the other main party in government, the pro-business League, is opposed to nationalisation.

“It may be difficult for the government to move from propaganda to decisive action. Autostrade will be their first reality check,” says Mr Orsina. “The contract is very clear” about the penalty to be paid by the government, adds Vittorio Carelli, an analyst at Santander.

In the interview he gave last week, Mr Castellucci remained defiant. Nationalisation of the road network, he said, would be “an incoherent return to the past, in total contradiction to the western world”.

Fragile coalition: the government is split over how to respond to the Genoa disaster

The Genoa bridge disaster has deepened fractures within Italy’s new coalition government — pitting Luigi Di Maio of the anti-establishment Five Star Movement against Matteo Salvini of the far-right League.

Facing its first major emergency, both leaders have united in laying much of the blame for the failure on Autostrade per l’Italia, Italy’s biggest toll road concessionary. But they are divided over what to do next.

For Five Star, the tragedy has been an opportunity to slam corporate greed, one of its campaign battle-cries.

Mr Di Maio has repeatedly called for the re-nationalisation of the motorways. “It is the state’s work to manage this kind of infrastructure,” he says.

But Mr Salvini, the other deputy prime minister is more hesitant. Mindful that cancelling the license could cost the government billions and involve a long legal wrangle, he is leaning towards a compensation settlement for the victims’ families, Genoa city and rebuilding costs.

He proposes tighter rules on concessions and increased powers for regulators. “I’m not in favour of nationalisation or state control,” he says, favouring a “clean relationship” between public and private sectors.

Five Star is also seeking a debate on all 35,000 state concessions to private business, including the television licenses owned by Silvio Berlusconi. But although Mr Berlusconi’s Forza Italia is not part of the government, the League could join forces with it in elections if the coalition were to collapse, which means it would not support such a challenge to Mr Berlusconi’s interests. Such a move would also hit its business supporters.

The coalition partners do still share some common ground, notably their hostility to the EU. Having initially tried to pin blame for the accident on EU spending restraints, both parties intend to use the disaster to push for more flexibility in the autumn budget.

Comments