Over $9tn of bonds trade with negative yields

Simply sign up to the Global Economy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

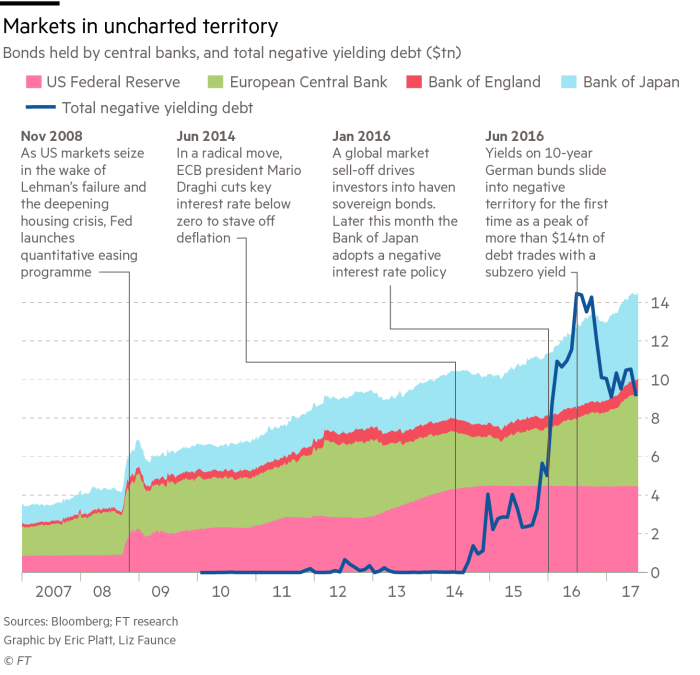

Central banks’ response to the financial crisis turned the normal rules of the bond market upside down. Bondholders typically expect to be paid interest to make up for the risk they might not be paid back. Yet trillions of dollars of debt is trading at prices so high that the yield is negative; buyers of the bonds who hold them to maturity are guaranteed to lose money.

Led by the US Federal Reserve, central banks have themselves become huge buyers of bonds, driving up prices and pushing yields below zero. This policy of quantitative easing was meant to reduce interest rates for business and personal borrowers, stimulate growth, buoy inflation and force money managers out of safe haven investments.

From less than $1tn in 2007, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet has more than quadrupled in size. As the financial crisis spread to Europe and Japan, the European Central Bank, Bank of Japan and Bank of England joined in the expansion. All told, the balance sheets of the four central banks have surpassed $14tn. With the Swiss National Bank and Sweden’s Riksbank, that figure climbs to $15tn and accounts for a fifth of the six countries’ total government debt.

Along with central bank interest rate cuts — including setting unprecedented negative rates in Europe and Japan — the bond-buying programmes explain why $9tn still trades with a negative yield, and why sub-zero rates are a reality that investors likely have to contend with for years to come.

Was the expansion of central bank balance sheets critical to the resolution of the financial crisis and to the global economic recovery? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Comments