A fight to remember: the visual arts in Peru

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Barranco, a 19th-century summer resort in Lima overlooking the Pacific, has a growing cluster of artists’ studios and galleries. In a white, early 20th-century villa, work in the Livia Benavides Gallery includes an exquisite semi-abstract painting of tiny rubber tyres on a gold background by William Córdova, who grew up in Peru and Miami, and Chinese-ink drawings by Fernando Bryce, a Limenean who spent 25 years in Berlin. Contemporary art now has vital support from local collectors, according to gallerist Livia Benavides, and Bryce’s work will be shown by Galerie Barbara Thumm at Art Basel Miami Beach.

“Peru’s link with the past is strong,” says the critic and curator Fietta Jarque, citing Inca mythology in the abstract paintings of Fernando de Szyszlo, who died last year. Victor Delfin’s monumental sculpture “The Kiss”, in Love Park in neighbouring Miraflores, recalls erotic sculptures in the city’s Larco Museum, a private collection of pre-Columbian art in an 18th-century villa, which opened in 1926. Barriers between “high” and popular arts have meanwhile been breached. Now, Jarque says, “you have indigenous artists and video installations in the same space.”

Peru’s ancient past invites comparison with Mexico. Yet, “Mexico had a revolution — a democratic nationalist one. We did not,” Bryce tells me in his studio in a high-rise in San Isidro district. State support came late to Peruvian art and the Museum of Art of Lima (MALI) only opened in 1961. Its excellent survey ranges from contemporary work to abstract Inca art, with colonial painting after the 1532 conquest. Anonymous indigenous artists, taught to imitate Italianate and Flemish oil painting, inserted local flora, fauna and symbolism into Catholic scenes — hence angels with multicoloured Amazonian wings, or guinea-pigs (an Andean delicacy) served at the Last Supper.

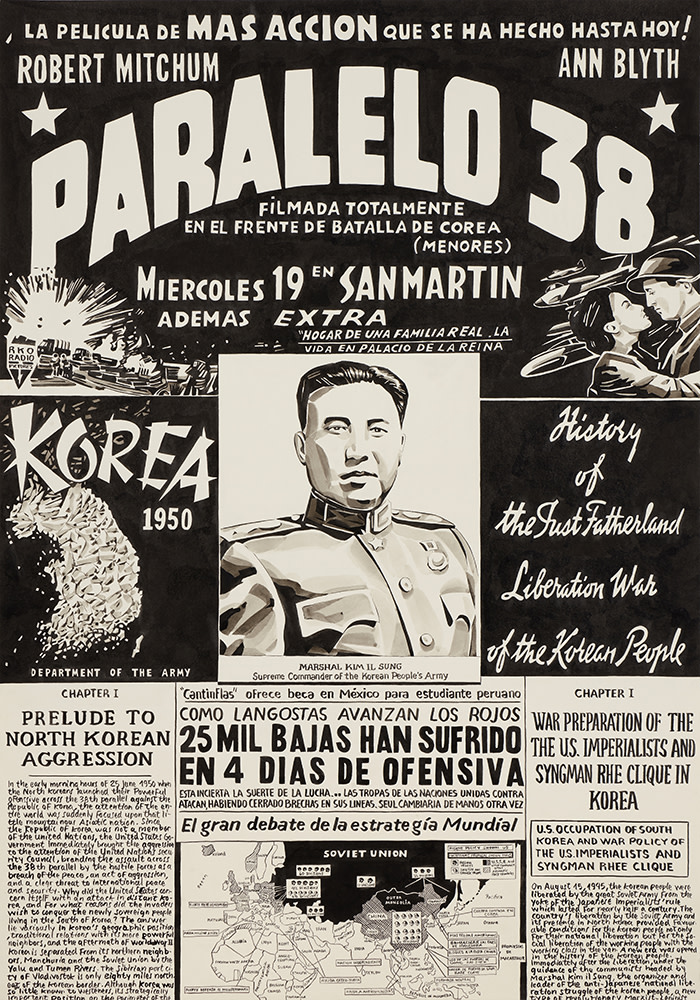

Bryce’s ink-and-brush drawings on paper probe Peruvian history with a conceptual twist. “Atlas Perú” (2005), a book of 495 drawings, is his compendious review of “how the representation of the country changed. In the 1990s Peru’s cultural identity disappeared: we were consumers not citizens.” Advertising, official documents and tourist images are all reproduced to ironic effect.

Peru was a “Latin American Albania”, he says of the 1980s and 1990s, decades of isolation when Maoist guerrillas of the Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) terrorised civilians. Political violence — three-quarters of whose 69,280 victims were rural Quechua-speakers — spawned a wave of memory-themed art. Yet 15 years after the 2003 Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR), such art is still heavily contested.

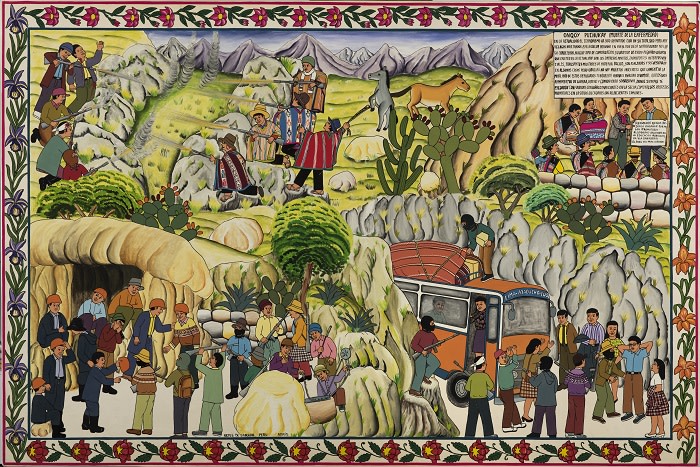

“People couldn’t believe this happened in Peru,” says Edilberto Jiménez, 57, who depicts atrocities he witnessed, or heard of, in 1980-92 in his home province of Ayacucho, centre of the genocide. Along with drawings, 26 retablos (boxed tableaux of wooden figures usually associated with religious themes) were on show earlier this year at the Place of Memory, Tolerance and Social Inclusion, a museum of the conflict that opened on the Miraflores cliffs in 2015, and where I meet Jiménez. Made over the past 28 years, his retablos include “Asesinato de niños en Huertahuaycco” (2007) portraying a massacre of children by the Shining Path and graphic scenes of rape and torture by the military and Sinchis (counter-insurgency police).

From a renowned family of retablistas (“From age eight, I helped my father,” Jiménez says), he broke with tradition to “show what was happening in daily life”. As a Quechua-speaker who had studied anthropology, he later collected evidence for the CVR on Chungui, a devastated community. “I couldn’t take photos — people were crying — so I started to draw. I lived violence and needed to express it, and my artistic language was the retablo,” he says. “Now I understand its value as memory.”

This year for the first time his retablos were exhibited in public. Others were destroyed by the army or police before the Institute of Peruvian Studies stepped in to protect them. “So many are lost,” he says. “I’m still making work from memory; it’s important everybody knows what happened.”

“Traditional artists were the first chroniclers of the war,” says Karen Bernedo, a curator who works on memory. Some had to destroy their work; others sent it abroad. “Piraq Causa?” (“Who is to Blame?”) is a series of 24 Tablas de Sarhua — painted boards customarily given as housewarming gifts in Sarhua, but depicting local atrocities. Made by a collective in the 1990s, they were preserved in the US and gifted to MALI. On their return to Peru last year they were seized by customs under laws forbidding anyone to “exalt, justify, or glorify terrorism”. “Piraq Causa?” is now part of an exhibition, Memories of Anger, at the Carrillo Gil Museum of Art in Mexico City. But a showing at MALI will follow, and last month the culture ministry recognised painted tablas as cultural patrimony.

Peruvian artist Ishmael Randall Weeks tackles memory in sculptures such as a found styrofoam cup cast in copper to resemble the vessels found in Inca tombs. “Families go for picnics to the pyramids on Sundays and dump trash,” he tells me in his Barranco studio. “I metallise the things left behind. This is a country layered by culture; and my work is part of a dialogue about ethics: do you throw garbage in your own patrimony? And how do you recover things from the past and bring them into the future?”

Born in Cusco to US parents, Randall Weeks grew up among Quechua-speakers — “an Andean white man with hippy parents” — and now moves between Brooklyn and Lima. Recalling the curfew in the 1980s, he says, “Cusco was a government-protected tourist zone. Ayacucho, no one cared, so the military attacked. Lima was oblivious till there were bombs in their nightclubs.”

In Arequipa, Peru’s second city, whose white stone cathedral is spectacularly backed by Andean volcanoes, the artist Jesus “Choqollo” Álvarez, 34, adopted a disparaging term for homosexuals as a pseudonym. He spoke last month at Hay Arequipa, an offshoot of the British literary festival. Because of the colonial past, he tells me, “trans people don’t have history. My work tries to gather these memories.” His Holy Week street performances aim “to give up on Catholic dogmas,” and in a Valentine’s Day work he exchanged clothes with a woman artist. As much as the brief public nudity, “it was shocking for people to see me in women’s dress.”

Two years ago, Choqollo “travestied” the Peruvian flag, printing the coat of arms on pink dress fabric, inspired by the sewing skills of his indigenous mother. Before the conquistadors, “indigenous people respected androgynous identities, and women were political leaders,” he says. The flag was one of two works that led to a group show in 2016 closing early.

Now, he says, “there are no galleries for me, so I will take to the streets.”

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments