Quentin Blake’s progress

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Early in his career, Quentin Blake spent just over a year as a part-time English teacher at the French Lycée in London. In conversation he is rather dismissive of this period, because by then he knew that illustration was his life: he had been doing it professionally since the age of 16, when his first cartoons were published in Punch, and school-teaching was just a safe supplementary income. But those he taught have a different appreciation of him. While I was working with him as consultant curator for an exhibition at the Petit Palais museum in Paris in 2005, we ran into Gilles Dattas, a gallery security guard and former Lycée student of Blake’s. It was more than 40 years since Dattas had seen Blake but the warmth of his response was palpable:

GD: “You used to read us stories, no other teachers did that, they were all very set in their ways, [it was] very Cartesian . . . a very French school. And we did a school play with you . . . it was Julius Caesar.”

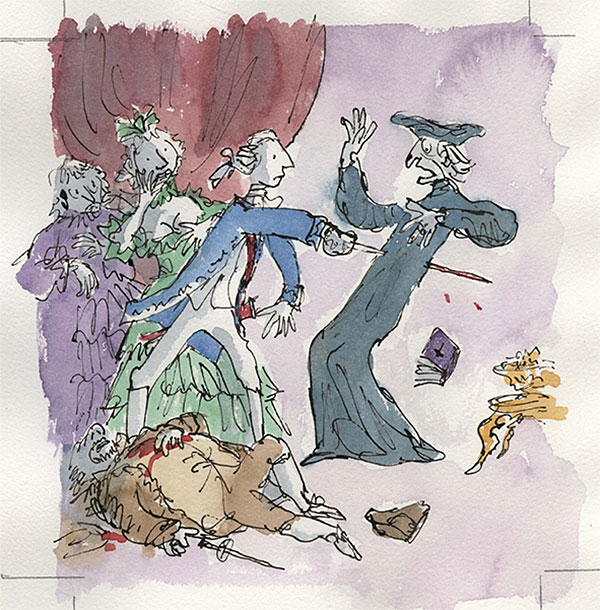

QB: “I was thinking about it the other day, because everyone knew their lines! I was quite worried, because it was a very short version, but even so quite a lot to learn. For the assassination we had three kinds of blood, various different people brought their own versions of home-made blood . . . ”

GD: “And they put it in water pistols! Yes! And they were wearing bed sheets and we all sort of clung together while Julius Caesar was getting stabbed, and one of them had this water pistol spraying the bed sheet with red ink.”

In this exchange we encounter another Blake, the man behind his most familiar drawings, those defining illustrations he made to Roald Dahl’s children’s books — The BFG, Matilda, The Enormous Crocodile and so many others. Here we have sight of an enlightened, offbeat teacher who understands the primary role that stories play in engaging minds; at the same time, we discover an unassuming personality that is by no means incidental to his work.

Blake is more than a cartoonist (though this should not be taken as a slight to that profession). His work, often so apparently light of weight, does indeed show us a man in line with a scratchy, witty British graphic tradition stretching back at least to James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson. But he is equally at home in European fine art, in his painterly heroes Goya and Rembrandt and in his beloved Daumier.

This close connection with the western canon was in evidence when Blake was chosen as Britain’s first Children’s Laureate in 1999: one of his declared aims for his tenure was to break down the barrier that exists between fine art and his own art of illustration. To this end, he approached the National Gallery and proposed an exhibition in which he hung contemporary illustration alongside works from the gallery’s collection by Uccello, Goya and Tiepolo, among others. The rationale was that audiences, especially young ones, have no problem decoding book illustration; why not therefore apply those same looking skills to the kind of art whose content and form might at first seem dauntingly alien?

Such a democratic approach may reflect Blake’s own route into art. He was a clever grammar school boy who went to Cambridge but, as far as his artistic skills and understanding of images are concerned, he was more of an autodidact. Born in 1932, he grew up in the south London suburbs; his family was not of the picture-owning classes. But his drawing talent was evident by the age of four. He did not go to art school (his only formal training was a term or two of life classes) and as a young teenager his discovery of fine art was neither at home nor school but at the home of the cultured family who lived opposite.

To illustrate what sets Blake apart and makes him such an unusual and effective communicator, it is worth giving a few images the kind of detailed attention not normally granted to works of this sort. Some of the most sensitive are to be found in The Story of the Dancing Frog, a 1984 book ostensibly for primary-age children, written as well as illustrated by Blake. Like all the best works for young people, it operates on many levels, weaving themes of death, widowhood, suicide, ageing, single parenthood, feminism and disappointed love into a fantastical animal story. Parallel storylines suspend the tale of Aunt Gertrude, a new widow who becomes an impresario for an astonishing dancing frog, alongside that of the narrating mother — the latter captured in five reassuring sepia-tinted drawings (below) that root us in the storytelling act.

The first of these is a skilful piece of scene-setting: Blake gives us all of the information we need in a few penstrokes: the two figures are probably related; they certainly have a warm, trusting relationship; family seems important to them (the shelf in between the two figures is full of photographs); the briefcase by the chair suggests that the mother goes out to work (later, Blake quietly hints in the text that the father is no longer around), and the child, Jo, is a reader who has set aside a book to hear a story from her mother (neither the name nor the illustrations make it clear whether Jo is a boy or a girl). All of this comes before we have read a word of text.

Towards the end of the book, another sepia drawing takes account of the time that storytelling takes. Cups of cocoa have been made and drunk, biscuits eaten; there is a kind of rapt closeness between the two, which anyone who has shared a story with a child will recognise. The last few lines of text reflect on what has passed:

“No one could really catch a frog and put it on the stage?”

“You can do all kinds of things if you need to enough.”

“Yes, I suppose so.”

So Blake can write, too. He read English at Cambridge (the critic FR Leavis was his tutor at Downing College) and his knowledge of literature, both English and French, is wide and deep. He is regularly commissioned by the Folio Society to illustrate their classics of world literature and also makes suggestions for texts to be republished; Voltaire’s Candide was one such idea.

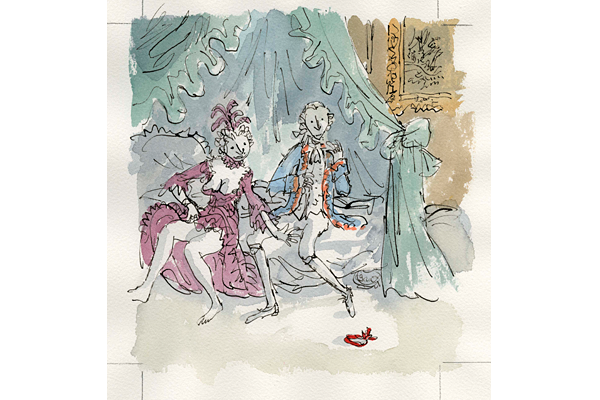

Blake’s response to the challenge of illustrating this 1759 satire was a series of 15 colour plates, as well as several black-and-white vignettes. The illustrations are close in spirit to the work: the costume is historical and the humour echoes that of the text, from belly-laughs to empathetic smiles. As Blake says: “Candide inadvertently running through an important cleric with his sword is farcical; while the garter-dropping marchioness [below] has to be real enough to be seductive.”

A very different side of Blake’s work can be seen in the images that he describes as “off the page”, projects undertaken over the past 15 years in public spaces such as hospitals, theatres and museums. One good example is a scheme to “illustrate” the walls of a maternity hospital in Angers, western France, commissioned in 2009 (top image). Blake has no children and had not visited a maternity hospital before — the nearest he had got to such a place, he implied to me in a quiet aside, was when accompanying a friend who was to have a termination. But he imagined himself into the situation, devising a theme of water, which worked both for the riverside setting of the hospital and the babies’ pre-partum amniotic home. Also in Blake’s mind was a notion of the weightless freedom that might be experienced by newly delivered mothers. The drawings have a gentle French Rococo swirl reminiscent of Boucher or Fragonard. They work at a symbolic level but, more directly, they capture “the exchange of look between the mothers and babies”, as the hardened hospital finance director marvelled when he saw them in situ.

Shortly afterwards, Blake was commissioned to make a series of works (above and below) for an NHS residential eating disorders unit in central London. He started the project by meeting staff and consulting with patients — on the whole, young people living with extremely poor self-images, some very seriously ill. These pictures are intentionally grounded, coloured, with bold contours. In them Blake proposes other ways to live, where the most basic elements of daily life could seem enjoyable and desirable even when they’re not perfect: you can go for a companionable walk in the rain; you can feed birds on your windowsill if you don’t have a garden (Blake later found out that there had, in fact, been a patient who invited pigeons into her bedroom); you can have a great night in slumped on an old sofa with a book and a good friend to do your hair, even if you don’t have a flat stomach. And Blake managed to insert the food message without ever lecturing: a dog sitting up for a biscuit, people buying fruit in a street-market, or the pleasure of pulling carrots in the vegetable plot.

While Blake, now in his eighties, continues to illustrate books — he has just finished work on The Tale of Kitty-in-Boots, a previously unpublished Beatrix Potter story for which she had only made one drawing — it is hard to imagine him producing anything more affecting than these hospital works, which seem to have summoned in him a new kind of empathetic but never sentimental artistic response to a brief. As a French teacher who worked with Blake on literacy projects in France once said to me: “I think if you took all of Quentin Blake’s work you could solve every problem in the world.”

Ghislaine Kenyon is a curator and consultant who has worked as deputy head of education at the National Gallery in London and head of learning at Somerset House. Her book ‘Quentin Blake: In the Theatre of the Imagination’ is published by Bloomsbury on March 10

Illustrations by Quentin Blake

Comments