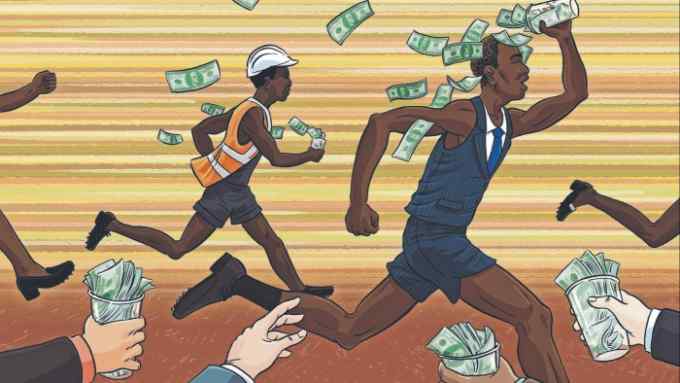

Studious investors stand to benefit from opportunities in Africa

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Africa presents something of a conundrum for the world’s biggest asset managers. What should be a continent overflowing with investment opportunities is by and large no more than a side note within the trading activities of many international fund companies.

Despite being home to some of the fastest growing economies, as well as an abundance of natural resources and a burgeoning middle class, it continues to be unloved by the majority of investment managers.

The number of funds that invest in the continent remains small, with data from investment research firm Refinitiv showing the single biggest individual Europe-focused fund holds more money than all of the Africa funds put together.

Liquidity, or the lack of it, is the sticking point. “For a lot of countries in Africa, getting your money back out is the problem,” explains Chris Tennant, a fund manager at Fidelity International, one of the world’s largest investment companies.

Illiquidity makes the situation “very difficult”, affirms Mark Mobius, the veteran investor. But scratch beneath the surface and the same fund managers say the continent can provide lucrative and stable returns — as long as investors are prepared to do their homework.

As the FT-Statista 2023 ranking of Africa’s fastest-growing companies shows, the continent has plenty to offer, in sectors ranging from fintech and renewable energy to healthcare, commodities and agriculture. However, many of the names in the 100-company list are effectively off limits to mutual funds and better suited to private equity investors who, as Mobius says, can make a “five or 10-year commitment without the pressure of needing to redeem”.

What countries, sectors and companies, then, do fund managers like? For Tennant, much promise lies in Zambia, commodities and the Canadian copper miner First Quantum Minerals. “I particularly like Zambia,” he says, noting that, as lots of commodity-producing nations implement windfall taxes and tighten tax regimes, Zambia is doing the opposite. President Hakainde Hichilema, since assuming office in 2021, “has improved the financial framework for mining companies” and is “pro-investment”, Tennant says. Coupled with the global move to electrify cars, and hence the growth in copper demand, this “makes a compelling case for Zambian mines, with First Quantum the standout name”.

Tennant also likes Namibia, which has a “very bright future” after a big oil discovery in the Orange Basin — the area’s third discovery in just over a year. “The potential for investors here is enormous,” he says.

Gregory Longe, portfolio manager of the Africa Frontiers Strategy at Cape Town-based Coronation Fund Managers, agrees. He has a significant holding in Africa Oil, a Canadian listed company that stands to benefit from its links to the recent Namibian discoveries. Africa Oil also has stakes in “high quality” oil producing fields operated by TotalEnergies and Chevron in Nigeria that will “generate more cash over the next four years” than the company’s entire market capitalisation.

“But what we are really excited about is that Africa Oil also owns a stake in the Venus oil discovery in Namibia,” he says, referring to the second of the three Orange Basin discoveries. “This field is currently being explored by TotalEnergies and is estimated to be a three to 10bn barrel field. It is TotalEnergies’ number one exploration priority for this year.”

Longe is also keen on Ugandan electricity distributor Umeme, despite the company being set to lose a key government contract in 2025. Reports suggest Uganda will form a state-owned electricity distributor to take over when Umeme’s concession expires next year, in an attempt to reduce power tariffs by cutting out the intermediary.

But Longe believes Umeme is undervalued. “The business has just generated $40mn in net profit, up 4 per cent year on year, and declared a $30mn dividend in the previous financial year. “The company is expected to keep growing earnings over the next two years, be debt free by year-end, and receive an estimated $250mn payout” when the government contract ends.

He adds that, up until December last year, Umeme had a market capitalisation of less than $100mn and that “needless to say” he was “very happy” to increase his fund’s exposure to the company.

“Since then, the share [price] has doubled, yet still looks very cheap trading on a 4.3x historical price/earnings ratio and 18 per cent historical dividend yield.”

Other companies flagged by asset managers as compelling investment opportunities include Kenyan telecoms group Safaricom, South African retailer ShopRite, and metals producer Jubilee Metals, which operates in Zambia.

Overall, though, the sense from the international fund community is that the continent is still more full of promise than anything else. “Africa remains hope eternal for global investors,” says Gary Dugan, Dalma Capital’s chief investment officer. “A continent rich in resources, commodities and people [that] still struggles to live up to the aspirations of the people and international investors.”

But he adds that “there is more persistence to efforts by the international community to help Africa realise its undoubted potential . . . Many of the emerging markets of the world have emerged, most notably China, and investors are seeking new ones. Maybe Africa can eventually deliver.”

Comments