Patients attack doctors for India’s healthcare failings

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Rohan Mhamunkar, a 35-year-old orthopaedic doctor, was on duty at Maharashtra state’s Dhule Civil Hospital late on a Sunday night in March when two men who had been badly injured in a motorbike accident were brought to the facility by their families.

One had suffered a severe head injury and was bleeding from his nose, mouth and ears. Dr Mhamunkar advised that the patient be taken to a hospital with a scanning machine and neurosurgeon available. The family duly took the patient and left.

But when the man died several hours later, his furious relatives returned to the Dhule hospital and attacked Dr Mhamunkar, accusing him of fatally delaying treatment. He was punched and kicked so badly that he suffered several fractures including damage to his eye socket that threatened his vision.

The attack at Dhule was the latest in a growing series of violent assaults on doctors by patients and their families, infuriated by the poor state of India’s public hospitals.

Increasingly, when patients fail to obtain timely treatment — or do not survive critical illnesses and injuries — families take out their frustration on the doctors who are on the front lines of the collapsing system.

Their anger is a symptom of the deepening healthcare crisis enveloping India, where overburdened public hospitals are unable to cope with the flow of patients seeking treatment — and private hospitals are far too expensive for the vast majority of people.

“This reflects the malaise within Indian healthcare,” says Dr Vivekanand Jha, executive director of the George Institute for Public Health India. Such attacks need to be seen in “the context of the general resentment in the minds of the public against the healthcare system,” he adds.

In theory, India has a network of primary, secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities that should be free to patients. In reality, however, these facilities often lack basic supplies and working equipment.

“It’s a system failure,” says Dr Mathew Varghese, head of orthopaedics at St Stephen’s, a Catholic hospital in New Delhi. “Doctors are on duty for 24 or 48 hours. They don’t have equipment. Dialysis machines are not working. CT scan machines are not working. Doctors have to send patients back and forth.”

In the end, patients are forced to turn to private hospitals, which can often lead to poor families ending up deep in debt.

“Patients are hard pressed to find the money,” says Dr Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India. “Even the public systems result in lots of out-of-pocket spending. Patients are told they have to buy medicines or get tests in the private market.”

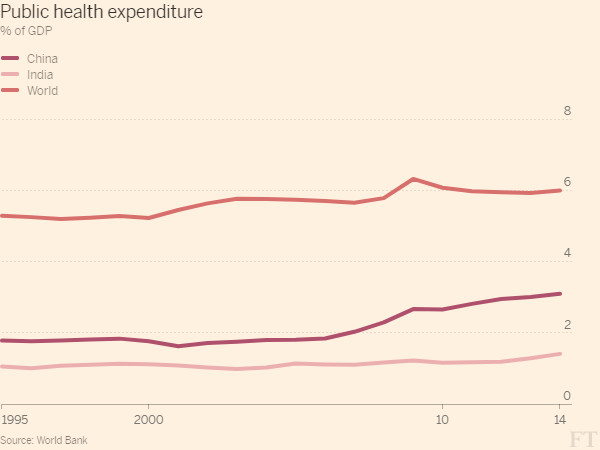

Conditions are unlikely to improve any time soon. India spends just 1.4 per cent of GDP on healthcare — well below the 6 per cent world average and the 3.1 per cent spent in China, its more affluent rival.

India also suffers an acute shortage of healthcare professionals. It has just one physician for every 1,800 people, well below the World Health Organization recommendation of one per 1,000.

The Medical Council of India says the true ratio may be even worse — possibly as high as 1 per 2,000 people — as doctors who retire, die or leave the country for good often remain registered and are counted in statistics.

Meanwhile, public expectations of healthcare systems have risen sharply in recent decades, fuelled by television dramas set in western hospitals and the slick advertising campaigns of India’s private hospitals touting their high-tech treatments.

“Medicine is advertised as something that can do miracles, but we cannot save patients all the time,” says Dr Varghese. “The system has raised expectations but cannot deliver all and cannot save all. The government system has neither the technology nor the resources.”

In the bitter clash of high expectations meeting the grim realities of India’s public hospitals, junior doctors working long shifts in emergency rooms become easy scapegoats.

According to a study carried out last year at a large hospital in New Delhi, 40 per cent of the medical residents had been exposed to violence in the previous 12 months. The Indian Medical Association has said that 75 per cent of Indian doctors have been attacked either physically of verbally by patients’ families at some point.

“People are thinking the doctor in the white coat must be enjoying a very nice life because of the taxpayer,” says Dr Vijay Kumar, president of the resident doctors’ association at the prestigious All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS). “We are trying to tell the general public, ‘we are also sufferers of the system like you’.”

After the attack on Dr Mhamunkar in March — and four other recent attacks on doctors in the region — medical residents in the Indian state of Maharashtra went on strike for more than five days to demand better security at hospitals. They returned to work on the orders of the Bombay High Court, which directed the government to ensure doctors were better protected.

At AIIMS, medical students are taking courses in the martial art of taekwondo so they can defend themselves against attack. “If you are not able to admit a patient who is serious because of the non-availability of beds, what can you do?” says Dr Kumar. “You never know when you will get hit by the patients’ attendants.”

Comments