Gamers prepare for cloud computing power-up

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Halo 2 was the video game that became a game changer. Released in 2004, it connected players across the world at the click of a button, allowing users of Microsoft’s Xbox console to voice chat, play different game modes or even challenge complete strangers.

Today, game developers are tantalisingly close to another watershed moment: the advent of “cloud gaming”. Thanks to improvements in telecommunications and data storage, significant computing power is no longer required on a local device; instead, games can be streamed from a data centre directly to a smartphone.

For the 2.7bn active gamers worldwide, cloud services like these promise unfettered access to thousands of digitally stored games — titles that previously could only have been played on a console or high-spec gaming computer. And this is just the beginning. In an arms race to bring new games to market, companies are experimenting with cloud-enabled features and designs.

It is an escalation that has been driven by soaring demand during Covid lockdowns. “As a result of the pandemic, we pulled forward about three to four years of video game adoption in the US,” says Brian Nowak, a managing director at Morgan Stanley Research who covers the US internet industry. In pandemic-hit 2020, the number of Americans playing games increased by 50m, compared with growth of 11m in a typical year.

Yet the need to pay a few hundred dollars for a console had previously been “a point of friction” in moves to encourage more people to play video games, explains Nowak.

Now, tech giants look at the sudden increase in housebound gamers and the growing market for cloud gaming, and see an opportunity to cash in. According to data group Grand View Research, the market for cloud-based gaming is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 48.2 per cent between 2021-27, to reach $7.24bn.

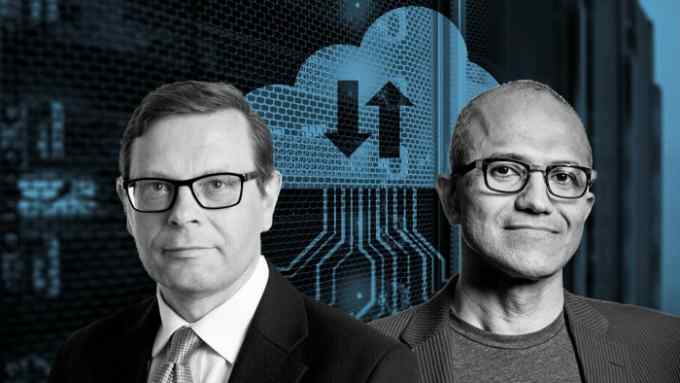

Already, the near duopoly of Microsoft and Sony in the gaming console business has come up against stiff competition in the cloud, where their streaming products — Xbox Game Pass and PlayStation Now — must contend with new entrants such as Amazon’s Luna and Google’s Stadia.

Even the chipmaker Nvidia, whose graphics processing units provide the basic architecture for much of the industry’s products, decided to shore up its position in the PC gaming market by launching its own online streaming platform, GeForce NOW, in 2020. Nvidia has more than two dozen data centres delivering a library of 2,000 games to its users.

However, it is not just the usual suspects looking to move into this space. Facebook stands to gain from the cloud as it will be able to render more complex games than is currently possible through its web app, suggests Jason Rubin, the social media platform’s vice-president of play.

He adds that Facebook’s 300m gamers are less likely to think of the social networking site as a place to download and install apps, whereas streaming would be suited to how users interact with the platform across different devices.

At video game publisher Ubisoft, “cross-progression will be a feature in our games going forward”, says Chris Early, its vice-president of partnerships and revenue. “You could begin streaming from your work computer on Stadia and then load it up on your PC later when you are home.”

This has led Ubisoft into a partnership with Amazon to offer its content through a dedicated channel on Luna — a strategy aimed at meeting consumers where they are.

If successful, these cloud platforms could bring about a change in the industry, says Nowak, as games publishers will demand better unit economics from companies — primarily Microsoft and Sony — than the 30 per cent cut they charge to run games on their consoles. Amazon says Luna will add more game channels “in the coming months”.

Meanwhile, the console makers are looking to strengthen their offerings.

Microsoft’s strategy is threefold: content, community and cloud, according to Kareem Choudhry, corporate vice-president of gaming cloud.

With the recent $7.5bn acquisition of publisher ZeniMax, Microsoft has buttressed its arsenal of in-house creative studio teams from 15 to 23. “Having a staple of first-party content is critical to our success,” says Tim Stuart, Xbox chief financial officer, “not unlike how Netflix might think of [TV series] Orange is the New Black or Stranger Things”,

Indeed, premium content has been the driving force in converting 18m of Xbox Live’s 100m active monthly users to Game Pass subscribers. Their increased engagement is an invaluable resource in its own right, as user data has already inspired in-game improvements, such as touch controls for mobile devices.

This feeds into the community-building element: what Rubin calls “a superpower.” Beyond the regular pool of gamers, there are a further 400m people who watch or discuss games on Facebook. Gaming companies see these communities as largely untapped markets waiting to be explored.

But even with all this technology, “it is still really hard to make good games”, says Nowak. He points to last month’s departure of Assassin’s Creed co-creator Jade Raymond from her role as head of Stadia’s creative studios after Google closed its in-house game development unit. “The only way these cloud gaming platforms are going to take off is if you have differentiated content that you can’t get anywhere else,” he says.

That is why streaming services must offer truly cloud-native games, where the extra computational power is leveraged to create “smarter and longer-lasting interactions with AIs that remember you”, argues Ubisoft’s Early. There is enormous potential for “choose-your-own-adventure” narratives, where the game reacts to your real-time choices.

However, it will take a blockbuster on a par with Halo 2 to showcase the cloud as a tool for innovation in game design — rather than simply another distribution mechanism.

Comments