Why junk bond yields are not so absurd

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The European Central Bank is worried about low-quality credit — it thinks there is too much sloshing around.

In its financial stability review, from earlier this month, the bank writes that: “Signs of exuberance are increasingly visible in some financial market segments as real yields fall and the search for yield continues. Real yields fell to all-time lows amid indications of a moderating pace of the economic recovery and increased inflationary pressures, incentivising risk-taking in financial markets. Issuance activity in high-yield corporate credit markets has reached new highs in 2021. Despite large issuance volumes, spreads remain at record lows, pointing to strong investor appetite for risky assets.”

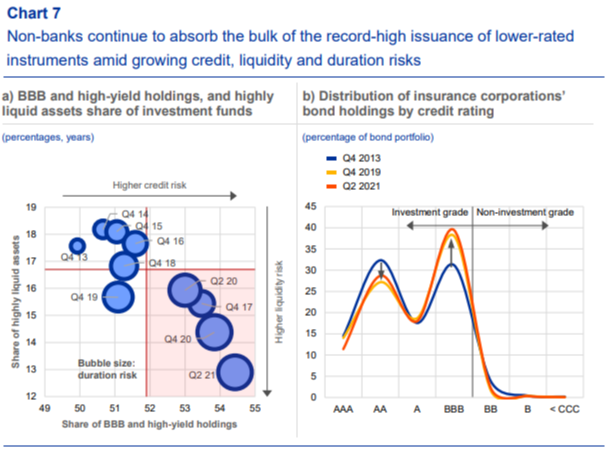

People are, undoubtedly, selling a lot of risky financial instruments, and other people are paying very high prices for them, all over the world. This is not news. But the ECB is particularly worried that investment funds and insurance companies, spurred on by the collapse of real yields, have piled into the risky end of the credit spectrum.

An ECB chart, in its report, showed increasing fund exposure to less liquid, lower credit quality assets. In particular, it demonstrated how insurance companies have significantly increased their exposure to the lowest-quality investment grade bonds — triple B rated bonds, in the jargon. The chart also gave an estimate of duration risk — that is, how much the funds holding these assets will get hurt if interest rates should spike (as they might do, if inflation gets out of hand and central banks have to tighten the screws).

Meanwhile, in the US, Bloomberg reported increased sales of riskier bonds: “US high-yield bond sales reached an annual record of $432.4bn [on November 16] as companies rush to lock in low coupons while they still can. Cheap funding costs have unleashed a prolonged pile-on of debt issuance, and borrowers have been hurrying to take advantage of the opportunity before the Federal Reserve eventually raises interest rates. That could come sooner than expected amid inflation pressures . . . This dash has taken 2021’s issuance beyond 2020’s high mark $431.8bn, which topped a prior record set in 2012.”

This wild demand for yield, and a benign economic environment engineered by loose fiscal and monetary policy, has had a predictable effect on junk bonds. They have become very expensive, and their yields are absurdly low.

The spreads — the degree of additional yield offered by riskier corporate bonds over sovereign debt — remain low.

European spreads have been, for months, at their pre-pandemic lows; US spreads are lower still. This seems crazy. Yes, corporate balance sheets and profits are both sparkling. But, surely, bond markets should be forward-facing, and we can recognise that the party is winding down.

The pandemic’s waterfall of fiscal transfers to consumers is drying up, the US government deficit will be smaller next year, central banks are starting to reduce quantitative easing, and a rate tightening cycle is expected to begin in the middle of the year. So shouldn’t spreads be creeping up?

Maybe not. Marty Fridson, chief investment officer at Lehmann, Livian, Fridson Advisors — and a longtime observer of the high-yield market — uses a five-factor econometric model of fair value in high-yield bonds. It takes in economic activity, the availability of credit, default rates, Treasury yields (which generally move inversely with spreads), and quantitative easing. And, as of the end of October, the model suggested that high-yield bond spreads were 124 basis points below fair value — about one standard deviation away from normal.

“It is fair to describe the market as expensive,” Fridson explains, but not massively so. He waves away the notion that the flood of issuance means yields must soon rise, saying that historically, issuance responds to demand, rather than the other way around.

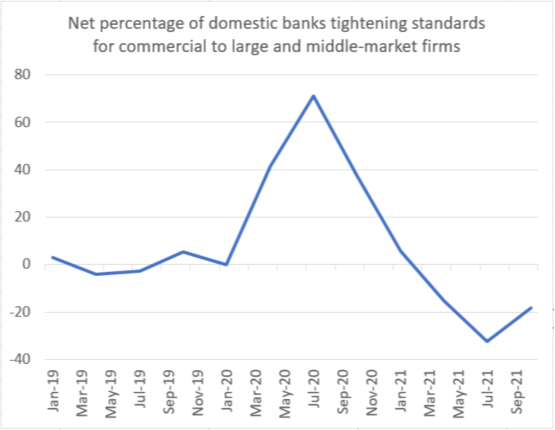

The key factor in keeping fair value low in recent months, Fridson says, had been greater availability of credit — which means companies have an easier time refinancing their debts and are less likely to default. Now, according to the Fed’s loan officers’ survey, the net number of banks tightening their lending standards has stopped falling, that is, credit availability has stopped increasing.

That may be an ominous sign. But there is another factor explaining the fall in spreads in the US, which Tomas Hirst of CreditSights has identified: the quality of high-yield bonds in bond indices has improved.

At the lowest-quality end, triple C rated and distressed companies have either gone bankrupt or, more frequently, repaired their balance sheets, meaning their yields have fallen from around 10 per cent to, say, 6 or 7. And there has been a lot of issuance at the high-quality end of the market: double B-rated bonds, the highest rung of junk, are now over half of the market — again dragging yields down. The index as a whole has become less risky.

So, the high-yield market may be hot and expensive. But spreads are not wildly out of line with history or with economic fundamentals.

If the ECB or any other central bank is looking for wild mispricing that presents a risk to financial stability, then they might want to look not at corporate bonds, but at sovereign debt — the market that they have been intervening in directly.

Comments