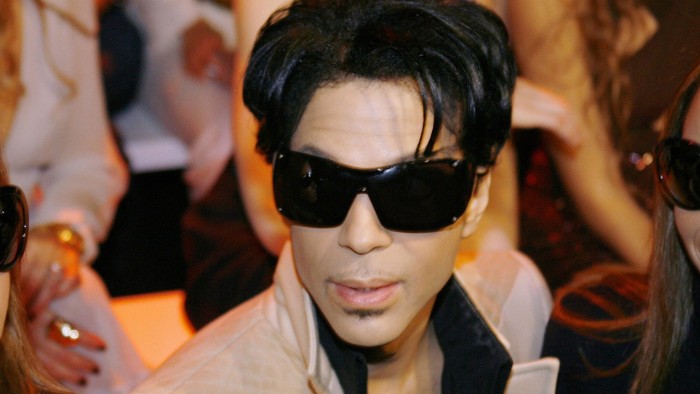

Prince wrote thousands of songs — but why didn’t he write a will?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

He has reputedly written enough unpublished songs to fill hundreds of albums, but it seems the one thing that Prince didn’t get around to writing was a will.

Court documents filed in Minnesota this week showed that the superstar, who died at the untimely age of 57, appears to have died intestate. The absence of a will has provided endless speculative fodder for the Hollywood gossip sites and tabloids.

Certainly, for a person of Prince’s great wealth (his estate is estimated to be worth hundreds of millions of dollars, rising fast with posthumous music sales) it is unusual. But I suspect that the reason Prince didn’t leave a will is rather simple. He probably didn’t plan on dying so soon.

The musical legacy Prince has left behind is unquestionable, but his surviving relatives are now left with the nightmare of resolving his financial affairs. Readers — let this be a lesson to you. If you haven’t made a will, or need to update one, seize the day.

Solicitors tell me one reason clients shy away from making a will is an irrational fear it will bring on their sudden death. Superstition is a powerful force, but the prospect of what could happen to your family if you die intestate should be a more powerful motivation.

Intestacy laws in England and Wales (on which I base all of the following observations) are not designed to cope with modern day families, says Paula Myers, partner at the law firm Irwin Mitchell. Couples who were living together but not in a marriage or civil partnership when one of them died feature frequently in cases she handles. Be warned: the term “common-law partner” and cohabiting is not something that our intestacy laws recognise.

A typical situation solicitors have to unravel is a divorced man with children, who moves in or buys a home with a new partner to whom he is not married. (The example could just as easily involve a divorced woman or a gay couple but the first is more common as men tend to earn more and die first.) If he dies intestate, his children — not his new partner — are entitled to his assets. If he didn’t get divorced, which is also more common than you might think, the estate passes to the ex-wife and not their children.

Ms Myers says that even if the new partner was named on the mortgage documents, she still might have to argue her case in court and “build up the jigsaw of evidence” — a costly and hugely stressful process. Plus, any award the judge would make would be limited to maintenance and no more.

Assume you die without having children or formalising your relationship. Our intestacy laws decree that your estate will pass backwards, to your parents (and not your siblings, as many believe).

Another thing intestacy laws cannot cope with is the huge rise in property values, says Andrew Wilkinson, partner at law firm Shakespeare Martineau. You might think — I’m married, so I don’t need a will. But if you die without a will, your spouse is only entitled to the first £250,000 of your estate (plus half of what remains after that). If your house is worth more than that, technically you’d have to sell it to divide it up.

So let’s suppose you’ve decided it’s high time you made your will. What next? You will need to appoint an executor. This could be a family friend or even a professional whose fees will be paid from your estate. Ideally, you would go to a solicitor to get it drawn up; many offer free consultations. This should cost between £300-£500 for a couple with relatively uncomplicated financial arrangements who want a “mirror will”, meaning assets pass to the remaining spouse, and upon their death, to the surviving children.

You can buy will writing kits on the internet, but solicitors tell me these are often a false economy and can end up being challenged in court. Yes, they would say that, wouldn’t they? But if cost is really an issue then many charities provide a free will writing service, providing you leave them a legacy.

Writing a will should form part of your overall estate planning, says Sarah Lord, partner at wealth manager Killik & Co. Consider who you want to get what, how they can get that taxed efficiently, and what other planning you need to put in place around this.

This will involve some searching conversations. To avoid a bitter court battle, it’s a good idea to consider what your children will receive if your partner remarries after your death. And if you have a second family, how will your assets be divided? If there is an unequal split (a parent leaving more to a child who has acted as their carer, for example) or an exclusion, a so-called “letter of wishes” can help relatives come to terms with your decision, though such letters are not legally binding. Better still, say the professionals, talk to your family about all of this while you are still alive.

Twitter

Follow Claer Barrett

@ClaerB

Two final things. Death-in-service benefits operate outside your estate. If you started your job a long time ago, you may need to update your beneficiaries. And if you’ve got around to making your will, you should also make a lasting power of attorney, allowing someone to make legally binding financial decisions in the event of your mental incapacity. You can do this yourself — for £110 per person — and the court of protection website will show you how.

With a minimum of forethought, you won’t leave your loved ones counting the cost when the music stops.

Claer Barrett is the editor of FT Money; claer.barrett@ft.com; Twitter: @Claerb

Comments