Desmond Tutu on God, Syria, Mandela — and laughter

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

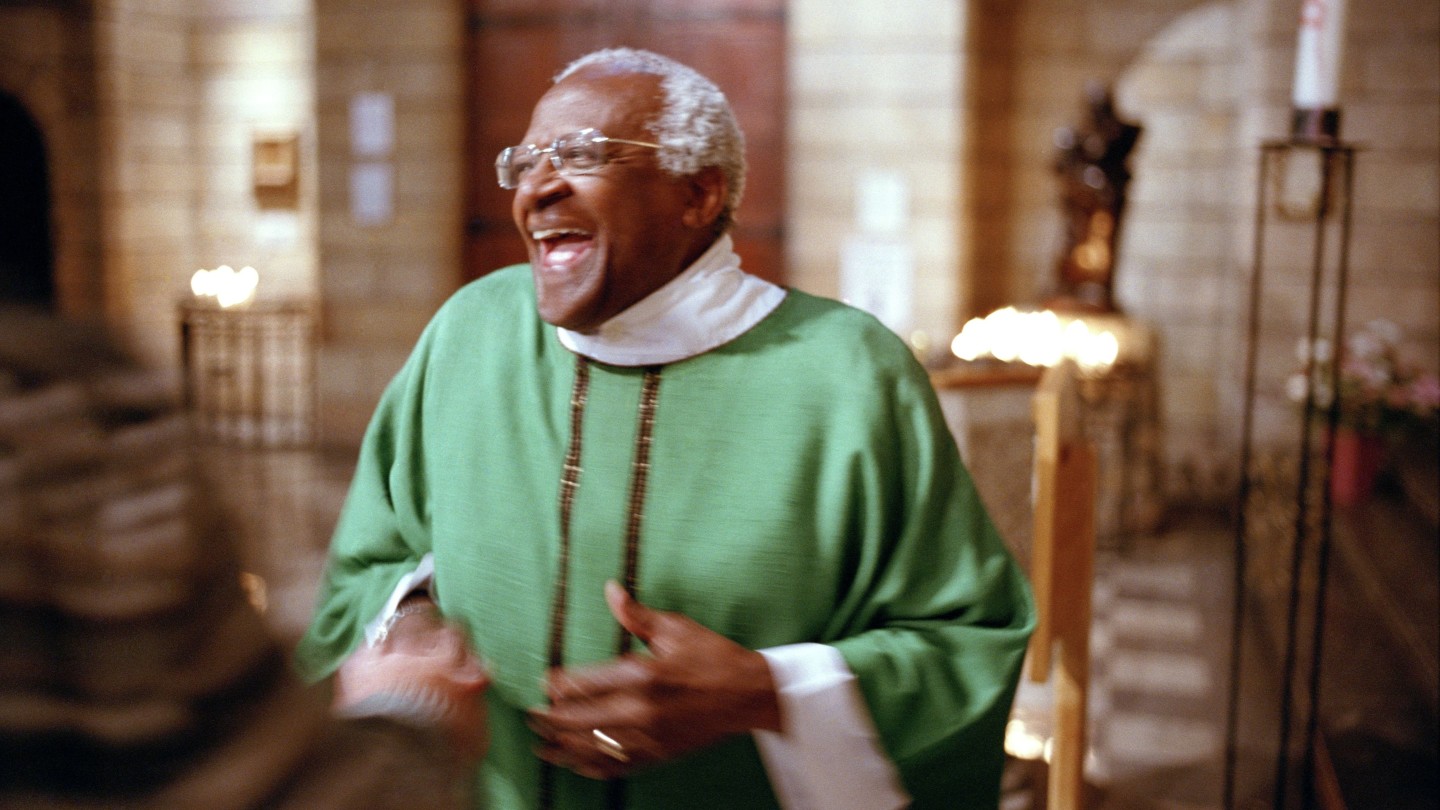

Desmond Tutu would have been a brilliant stand-up comic. Within moments of arriving at his foundation’s offices, sporting his customary black workman’s cap, he is teasing his staff, his visitors and most exuberantly, of course, himself. “You are toooo close,” he tells a charity photographer, shooing away his lens. “Makes my nose grow big.” When I ask after his right foot, which is in a cast, I think for a moment he has misheard. “She is very beautiful . . . ” Long pause. “The girl who I fell for . . . ” He chuckles, as does his audience, irrepressibly, even his staff who have surely heard this before. “Tendonitis,” he adds. “Teenage-itis,” says an aide.

An assistant wheels in the morning tea trolley. Visitors, staff, gather at his feet, acolytes before a sage. I anticipate a blessing. (Later, the formal interview begins with a prayer.) But “the Arch” is still in full flow. “You should put this on your CV,” he tells one of his aides. The diffident besuited white man is offering him, an ebullient reclining black man, a slice of cake, in an inversion of the classic apartheid tea-time tableau. “I,” Tutu says in slow staccato, “served — a — black — man — today.” Then, as if even that was not enough, he turns from lampooning the new to the old. As the same assistant sits down empty-handed, Tutu sucks in his breath as if a divine law had been broken. “Oh no! A white man . . . served last.”

That infectious giggle erupts again. It is a sound that rang around the world in the mesmeric days of the end of white rule. It was the archbishop, of course, who introduced Nelson Mandela to the crowds in Cape Town in 1990 on his first day of freedom in 27 years. He was the high priest of the transition. No one who was there under that diamond-bright sky four years later can forget his yelps of delight as he blessed and inspired the crowd at Mandela’s inauguration. It was Tutu after all who dubbed South Africa the “rainbow nation”.

Over the past 20 years I have encountered him dozens of times, laughing, crying, nudging, chiding, enraged. There were frenetic exchanges amid the maelstrom of the transition. There were formal interviews when he was confessor of the nation, presiding over the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, his audacious bid to exorcise its past. Then, more than a decade into democracy, there was a gloomy lunch at a fish restaurant, where he heaped opprobrium on the ruling African National Congress, as incompetent and rapacious, if not beneath contempt.

Now, on a crisp southern spring morning six years since our last encounter, the impish extrovert with the passion for the underdog, deep faith and love of contemplation — and also the limelight — somehow seems less anguished. He cuts a grandfatherly figure in his faded grey tracksuit. Two friends of his had told me his family is urging him to intervene less in the public debate. He is, after all, 82 next month and has had a 17-year fight against prostate cancer. But even as he aspires to spend more time reflecting, his old fire blazes as fiercely as ever.

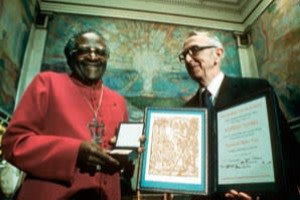

In recent months South Africans have been aghast and yet rapt as Mandela’s family has feuded over how to tend the frail national hero — and over who will enjoy the riches that will surely flow from controlling the Mandela name. Confidants of South Africa’s other beloved moral authority say Tutu’s advisers have taken note and moved to ensure the Tutu “legacy” is in safe hands. The youngest of his three daughters, Mpho, directs his foundation and its burgeoning network of charities. This year Tutu won the $1.7m Templeton Prize for spiritual leadership, following in the footsteps of Mother Teresa, the Dalai Lama, Billy Graham and others. His foundation is run from a nondescript office in a business park five miles north of Cape Town. John Carlin, one of the great post-apartheid chroniclers, once wrote that there was no one who can challenge our lack of faith like Tutu. As Tutu and Mpho discuss their faith in the foundation’s office, scattering references to God as if talking of an old friend, I appreciate how true that is.

Mpho, 49, an ordained priest, is an obvious keeper of her father’s flame. She had the peripatetic childhood of all four of Tutu’s children. They were spared the indignities of Tutu’s early years as a third-class citizen but they and their mother Leah, an unordained Anglican minister, paid a price, having to move every few years as Tutu rose through the church. Trevor, the only son and something of a tearaway, has been a repeated cause of concern for his parents.

Mpho is less voluble than her father — how could she not be? But they interrupt and tease each other at will as any loving father and daughter might do. When they laugh together, they crackle with the force of a high-veld storm — not least when I recount the decline and fall of our local Anglican church in west London, exhibit A in my contention to them that their church is in deep trouble in the west.

It was a grand Victorian church built to accommodate hundreds, I explain. Twelve years ago when one of our sons was christened there the congregation was barely a dozen strong. Now it is closed. “Is that the effect you had?” jokes the Arch. He urges his fellow Anglican clerics not to panic over suggestions that Britain is becoming a post-Christian society and their church is in long-term decline.

“Of course we [the Anglican Church] want to sell our product [and have full congregations] but in another way we ought to say ultimately it doesn’t matter that our churches are empty. We have to find a way of communicating with those who say they find churches off-putting. That doesn’t make them any less members of God’s family . . . How you actually get fulfilment as a human being isn’t when you rough everyone up and clobber them [for not attending church, for example]. It’s when you follow the example of the Lord, longing for the best for the other.” We shouldn’t be too selective, he adds. There really are churches where people are “well fed spiritually”. Then, characteristically, he changes tack, a trick he deployed so often in his searing sermons of the past. The trouble is, he concedes, tele-evangelists are filling a need.

“I’ve looked at our television here and you feel really sorry for what they [evangelical congregations] are fed. There’s a young pastor in Soweto I think. They must have two or three thousand people at a service every Sunday . . . but it’s real . . . ”

“Drivel,” says Mpho.

“I was going to say bull . . . ” He just stops. More laughter.

And my exhibit B, the success in the west of Richard Dawkins’ paean to atheism, his bestselling book, The God Delusion? Tutu is warming up now and delivers a confident riposte — though again, and typically, not what one might expect from a priest.

“God doesn’t want us being childish. God may want us to be childlike but not childish. We’ve been given intellectual gifts. We should go and question things we think are dubious intellectually. God is not sitting on edge that someone is going to find out eventually that the area of God’s control is shrinking. It’s not. God is not on edge. God says, ‘Bah!’ God is thrilled that we’ve been discovering all kinds of things. When you look at what science has discovered, God says, ‘Yay. There they go. That’s what I would like them to know.’”

As a cleric, Tutu has always defied rigid categorisation — if not flouted convention. At the height of the repression in the mid-1980s he embodied “liberation theology”. He ignored those superiors who thought he overstepped the mark. For him politics and religion were of a piece and had to be, in light of apartheid’s injustices. He also easily bridged the sometimes awkward gap between western and African traditions and thinking. John Allen, who was Tutu’s spokesman for more than a decade, wrote in an authorised biography that Tutu liked to contrast the western with the African idea of what it means to be human by setting Descartes’ “I think therefore I am” against the southern African tradition of ubuntu, which loosely means “a person is a person through other people”. Tutu thinks the west “has a tendency to separate the secular and sacred”, Allen tells me, “that it is very good at analysing and dissecting but not so good at integrating and pulling it all together.”

In this encompassing spirit, Tutu confidently pushes the boundaries: he makes clear his message is for all denominations and faiths. One of my sons, I say, was perplexed to learn that he, a former archbishop, had written a collection of sermons under the title God is not a Christian.

Look at “the imperialism we Christians practise,” Tutu replies. “We think we have a corner on God and that other people have a look-in because of our generosity in allowing them . . . You imagine when the Dalai Lama gets to heaven and knocks on the door and St Peter — and God — says, ‘You know, Dalai Lama, you are such a lovely person, you are so serene. What a pity you are not a Christian!’

“It’s weird. Look at Mahatma Gandhi. He inspired Martin Luther King. Do we really seriously believe that virtue is the preserve of Christians?”

His serenity about the future of Anglicanism wanes only when I raise the rift over gay priests. While he admires Rowan Williams for his intellect, Tutu clearly believes the former Archbishop of Canterbury should have led more strongly and backed the liberals against the conservatives.

“He spent most of his term trying to hold together disparate groups and we did not benefit from this person of very, very deep prayerfulness and scholarship . . . Our Lord was weeping. Our Lord who had come for the very specific purpose of saving the world looked on and saw a major denomination at a time of huge inequalities, poverty . . . ”

Mpho: “Famine flood pestilence. And what were we doing?”

“This Anglican Church, what are we doing? We’re spending time checking out who sleeps with whom. Our Lord must have said . . . Am I going to have to go and die again for us to . . . ?’”

Mpho: “To get it.”

Tutu’s public life has had two major incarnations. In the mid-1980s he was the impassioned face of the anti-apartheid movement. For the white government, he was the number one hate figure if not the Antichrist. Abroad, his oratory — framed by his customary imagery, arms outstretched as if on a cross — electrified public opinion and earned him comparisons to Martin Luther King. Enraged, he stormed through western capitals excoriating politicians over their reluctance to impose sanctions. It is this anger that makes his role in the mid-1990s all the more remarkable.

For two years he steered highly charged public hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission across South Africa. He trod a difficult path. The commission had quasi-judicial status. Perpetrators of what were deemed political crimes could be given amnesty if they confessed their guilt. Yet he deliberately brought a spiritual flavour to proceedings. He wept, he prayed, he preached. As the process developed, so he appeared to adopt a position that anyone was worthy of forgiveness, whether they confessed or not. Could you reconcile with anyone, I ask? What of Assad, is he beyond the pale? Are there not some people who just go too far?

I am speaking to Tutu 10 days after the chemical weapons attack in Syria, blamed by Barack Obama on Syria’s leader Bashar al-Assad. Tutu, a staunch critic of the war in Iraq, chooses to answer my question by turning to the New Testament. He invokes the parable of the lost sheep, which he suggests has been misunderstood.

“If you look at most of the images in churches, they show the good shepherd carrying a fluffy little lamb. Now fluffy little lambs are not known for wandering away from their mummies. The sheep that is likely to do so is that obstreperous old ram. It’s actually mind-blowing to think a good shepherd says, ‘I’m leaving 99 well-behaved sheep to go and search for this rogue.’

“And when he finds it he doesn’t pinch his nostrils. He gathers this thing up and says, ‘There is greater joy in heaven over this one than over the 99 who did not need to be found.’ That is an incredible statement about the divine . . . What?”

Mpho: “Madness!”

“You and I would say what lousy stewardship. How can you want to invest in this thing when you’ve got these lovely well-behaved sheep? You’d need your head read.”

I might say that but not you, I venture.

“No! It’s God who’s saying we have values that are turned upside down in heaven!” The Tutus reflect approvingly on Origen, the Alexandrian thinker, for arguing that even the devil would eventually be redeemed because he would not be able to resist the attraction of “divine love”. I return to Assad. Tutu endorsed the intervention in Kosovo in 1999, I say. I contrast that with a recent statement in which he warned against intervening in Syria. When I single out the use of chemical weapons as “appalling”, he and Mpho agree but they answer in monosyllables. Then Tutu erupts.

“Yes, but what then are you going to do [if you intervene]? You’re going to smash him [Assad] to smithereens and what do you put in his place? Because that’s not going to resolve the crisis of Syria, because you have all kinds of factions there. It’s better to try the long route, the kind of things Kofi Annan was trying.”

He recalls trying to speak to George W Bush to counsel against invading Iraq. He was, by a strange twist, with the then president’s brother, Jeb, at his home in Florida, when the White House tracked him down to say the president was rather busy. But what of the “profound wrongs” in Syria, I press? The Tutus are adamantine.

“We know it didn’t work in Iraq.”

Mpho: “So why are we going to try it again?”

“It didn’t work, breaking international law . . . When are we going to learn? The invasion of Iraq was a contravention of international law. They want to repeat it. And where are they going to bomb so they know it is actually Assad [being bombed]?”

Mpho: “Yes. Which people are walking around identifying themselves as ‘I’m on Assad’s side so I am going to wear a purple jersey,’ as opposed to the guys in the red jerseys [who] are on the other side.”

Tutu shakes his head. “It’s no. No.”

On his first night of freedom in 27 years Mandela stayed with Tutu at Bishopscourt, the archbishop of Cape Town’s official residence. That night arguably marked the moment Tutu handed over South Africa’s moral leadership to Mandela. (Tutu claimed it back nearly a decade ago when Mandela withdrew from public life.) It also inaugurated a warm if occasionally tetchy relationship between the two Nobel peace laureates.

Soon after Mandela took office, Tutu chided him for increasing MPs’ salaries and for not closing down the apartheid arms trade. When Mandela accused him of being a “populist”, he hit back, typically, though, tempering his attack with an affectionate critique of Mandela’s colourful shirts. Tutu had made his point. The ultimate pastoral interventionist was not going to let Mandela’s stature inhibit him from speaking his mind. To the irritation of the ANC he would retain his independence.

As the ANC became rather accustomed to the perks of power, so his critiques sharpened. In 2004 he lamented that only “an elite few” had reached the “promised land”. Just four months ago, he said that he would no longer vote for the ANC, citing inequality, violence and corruption as among the reasons for his loss of support. When I ask for his current thinking on the party, he turns to “a lovely quote in Isaiah”.

“‘Look to the rock from which you are hewn.’ We were hewn from a rock of people who were ready to lay down their lives for freedom . . . We have very many good things that are happening but you long for us to remember why we were in the struggle and what kind of South Africa we would love to see. We have accomplished a part of the dream . . . and some things subvert that dream.”

In keeping with the schizophrenic spirit of so many metropolitan South Africans who lurch collectively from rapture to gloom and back, the Tutus choose to marvel rather than despair. Mpho reflects on the rainbow hue of her seven-year-old daughter’s school. The Arch chuckles as he contrasts the absurdity of apartheid with the life of the “Born Free” generation.

“Go to the University of Pretoria, as I did, and there was a group of boys, all black, and there’s one girl walking with them and she is white. Well, walking would be stretching it a bit because she was in a clinch with a black guy. And I looked up at the sky to check if the sky was still in place.”

“Hadn’t fallen . . . ” interjects Mpho.

Two days after my interview a veteran ANC politician laughs ruefully when I mention Tutu. “He has had his own maverick streak for ever,” he says. “Sometimes you can’t win with him.” At his age, he adds, he should be allowed to retire gracefully, as Mandela did. “He is very spiritual,” the politician says. “You must just give him more time to do that.”

His comments reflect the piquancy of Tutu’s critiques for the ANC. By contrast, one of Mandela’s former ministers, who is now retired, feels able to extol Tutu’s qualities explicitly although he too only speaks anonymously. “Tutu is the best we have,” he tells me. “Better possibly even than Mandela was . . . Mandela you see had this imperious streak . . . ”

Tutu is not just the best that South Africa has. As a moral authority, arguably he is the best the world has. His great friend, the Dalai Lama, can match him for spiritual aura — and spry wit. But Tutu, the scourge of apartheid and now the sometime scourge of the ANC, has a voice that echoes across the world. Governments which have been stung by his rhetoric — from Israel to China, the US and UK — argue that he is too ready to declaim. But Christians and non-Christians alike celebrate his gift for casting aside the claptrap that can so stifle organised religion and focusing on what counts.

There is one last ANC occasion Tutu will certainly attend. Four days before my interview, the 95-year-old Mandela returned home from hospital after two months in a critical state. One confidant, who until two years ago spoke to him most weeks, confirms to me the widespread assumption that he has returned home to die.

Tutu will preach at the funeral. I remind him of a rambunctious foreign correspondents’ dinner in 1995 when he described the then president as “only one pebble” on the ANC’s beach — “although not an insignificant pebble”. Has his view changed?

“He’s special. He was indispensable. And many people get a little upset with me when I say the 27 years in prison was necessary for him to be able to evolve from a very angry young man, relatively young, to someone who emerged magnanimous, someone who was able to understand the Afrikaner.”

“Is he a saint?”

“In the making . . . like all of us.”

“Is it time that the family allows him . . . to depart in peace?” Mpho intervenes firmly for the first time. “That’s a decision for the family.”

“She is just making sure I don’t put my foot in it. I know her.”

John Allen, his biographer, quotes a nun who years ago told Tutu: “You’ve been a celebrity too long. It’s taken its toll not only on you but on those around you.” I put this quote to Tutu and ask why he still hasn’t retired.

“He has,” laughs Mpho. “At least thrice.”

“Yes I have.”

“Yes he’s retired. It’s a very gentle . . . ”

“Steep.”

“No, it’s a gentle incline, learning to say no. We were looking for a steep learning curve. It’s not happening, so, the gentle incline.” Mpho picks me up on my use of the “celebrity” quote. “It sounds as if he drives his own celebrity status. But it’s driven rather than drawn. What he sees is someone crying for help . . . and here is help that I can give.”

So has he ever held back from speaking his mind?

“No. I’ve not spoken up at a drop of a hat every time . . . even though sometimes it might have sounded so.”

I ask Mpho if he is ever silent around the family table. “Only when there is cricket on . . . ”

“I’m a very subdued, henpecked man,” says Tutu. Then he is serious again — at the last, as ever, because for all the warmth and wit and play-acting he is a deeply serious man. “People don’t believe I am shy but, by nature, I am. When I speak out, it is contrary to who I am. I’m fond of living peacefully. And I would naturally be ready to compromise left, right and centre. Yes. But I was taken by the scruff of the neck. And the rest is history.” Indeed.

Alec Russell is Editor of FTWeekend, a former South Africa correspondent and author of “After Mandela: The Battle for the Soul of South Africa”

Comments