The role of business in climate change

Simply sign up to the Climate change myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In October the FT Future Forum assembled a panel to discuss the role of business in tackling climate change. It featured Emmanuel Faber, chief executive officer of Danone, the food company, and Huw van Steenis, group managing director and chair of sustainable finance at UBS, the financial services group. It was moderated by Pilita Clark, a business columnist at the Financial Times.

The issue of climate change has been to the fore since the UN Paris Agreement in 2015, which aimed to limit the average rise in global temperatures to 2C above pre-industrial levels and to try to keep the increase below 1.5C. This target has been adopted by almost every nation on earth.

The pace of government activity has accelerated quickly. In 2019 the UK, New Zealand and France made laws that commit them to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. Sweden has given itself a goal of 2045. This year China, Japan and South Korea made similar promises, although their targets have yet to become law.

According to the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit, economies accounting for half of the global gross domestic product have made a commitment of some sort.

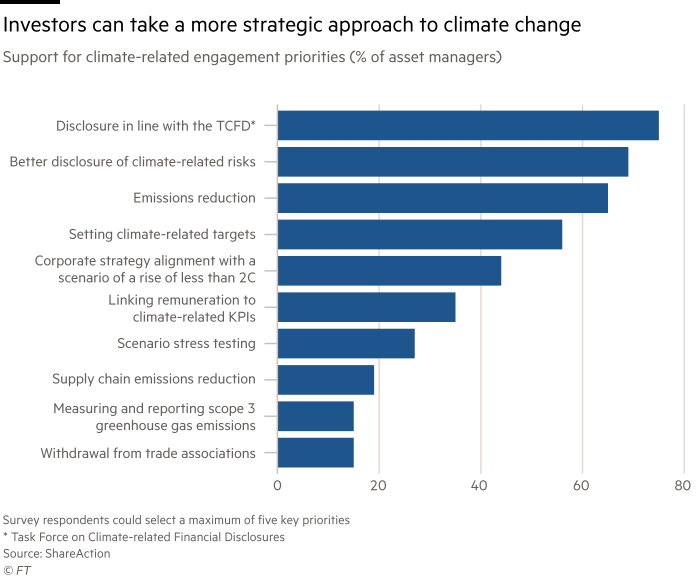

Even the US, whose withdrawal from the Paris Agreement took effect in November, is likely to return to the fold when president-elect Joe Biden replaces Donald Trump on January 20. The “Biden Plan” promises to invest $2tn in an “equitable green-energy future”. The urgency of the issue is shown by how quickly thought has turned into action. In November, Rishi Sunak, the UK chancellor, followed countries such as Germany and Sweden when he announced Britain’s first green government bonds to fund low carbon projects. He also said that from 2025 disclosure of climate threats would be mandatory for listed and large private companies under a framework created by the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). Disclosure is the first step but it is data that will allow companies and their investors to appreciate the risk posed by climate change.

Matthew Bell, the Asia-Pacific climate change and sustainability services leader for EY, the professional services consultancy, says: “Unlike a lot of these other standards, which are kind of point-in-time reporting, TCFD says what’s your business model and how is it impacted by these multi-decadal changes to the climate.

“It gets organisations to think about risk management and governance, setting metrics and targets and establishing a strategy to deal with existential threats — and that’s new.”

The challenge

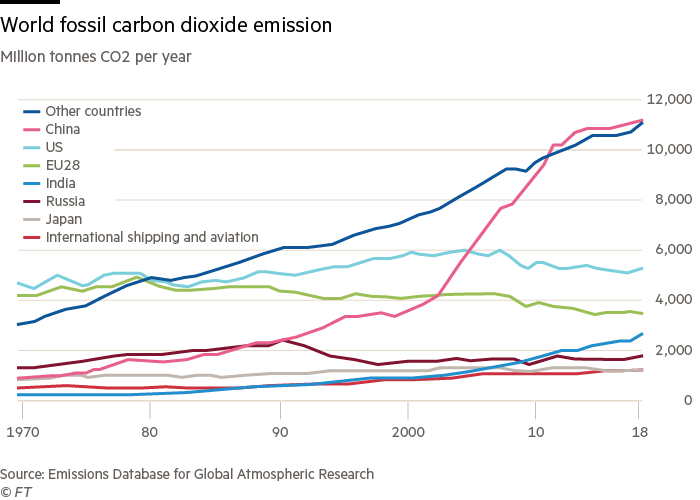

The challenge to reach net zero is huge, so practical action is a priority. The International Energy Agency says that by 2030 emissions must fall by 45 per cent relative to 2010 to be on track to reach net zero. Rapid progress, it says, is “crucial”. Success will depend on cleaning up energy sources, reducing emissions from appliances and retrofitting buildings, as well as making gains in efficiency to enable energy demand to fall by nearly a fifth, back to the level of 2006, despite the larger global economy.

All this will cost. A rule of thumb is that one to two per cent of global GDP will need to be spent to achieve climate goals. The OECD estimates that the necessary infrastructure will cost $7tn a year up to 2030.

Other data present an optimistic picture. In the UK, the opposition Labour party identified net benefits to the economy of £800bn if the energy sector’s net-zero target is brought forward and reached by 2030. A 2018 Stanford University study predicted a 60 per cent chance that keeping global warming within 1.5C instead of 2C by 2050 would result in accumulated global benefits of $20tn, although it does make caveats.

Progress to date

A first step towards lower emissions has been to clean up the power sector, notably coal-fired electricity generation. This seems to be working. In August, Global Energy Monitor reported in Carbon Brief that global coal-fired power capacity shrank for the first time in the first half of 2020, although countries such as China continue to expand.

In the UK, the effect of policies for greener economic growth and cleaner air has been marked. Emissions related to energy supply have declined. Provisional figures for 2019 published in March show that the sector’s CO2 emissions are down by nearly two-thirds since 1990, against an aggregate fall of 41 per cent. The transport sector is next. Having barely reduced its emissions since 1990, it ranks as Britain’s worst emissions offender.

Worldwide, policies are being put in place to deal with vehicle emissions. In 2019, France became the first country to legislate to phase out combustion engines, with a target year of 2040. By June, according to the IEA, 17 countries had announced 100 per cent zero-emission targets or the phasing-out of vehicles powered by internal combustion by 2050. In November, as part of the UK plan to tackle emissions, the government said it would ban sales of petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030, bringing that target forward by 10 years.

So far, in the UK at least, a reduction in emissions has had no effect on economic growth. The Clean Growth Strategy of 2017 said Britain’s economy had expanded by two-thirds since 1990: it outpaced other G7 nations and it also did better at cutting emissions.

The outlook for business

British business will not be let off the hook. In 2018 the commercial sector was responsible for 18 per cent of CO2 emissions, just behind homes. In the same year, US industry accounted for more than a fifth of greenhouse-gas emissions, according to a Senate Democrats’ report. In its 2019 progress report, the UK committee on climate change said: “It will be businesses that primarily deliver the net-zero target and provide the vast majority of the required investment”, adding that policy needed to give a “clear and stable direction”.

The UK, which is due to host the COP26 summit in Glasgow in November 2021, is priming companies for action with policies directed at specific sectors.

At the opening of the COP26 private finance agenda in February, before Covid struck in the west, Alok Sharma, the COP26 president and UK business secretary, highlighted the need for a shift in funding. “Only decarbonised economies”, he said, “will be able to grow through the worst impacts of climate change.”

Speaking later to business leaders, Mr Sharma noted that the fight against climate change “has to be a joint endeavour between nations, civil society and business”. He called on businesses to commit to targets such as sourcing 100 per cent renewable energy by 2050 and switching all vehicles to zero emissions by 2030.

The climate-related shift could be as transformational as the advent of the internet. Businesses that do not adapt will be at risk, while those that embrace change will see greater opportunities. Dr Bell describes climate change as “the greatest economic transformation in our lifetime, because it impacts on every single industry sector. Nobody’s immune”. Andy Howard, head of sustainable investment at Schroders, the investment manager, agrees. “[Given] the scale of disruption we are talking about, there won’t be any easy wins,” he says.

The Race to Zero Coalition, a global initiative under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, counts among its supporters more than 1,000 companies, 450 cities, 549 universities and 45 investors. Climate Action 100+, an investor initiative that started in 2017, includes more than 500 investors that urge companies into action on climate issues. CDP, which runs a disclosure system for environmental effects, publishes an annual climate action ranking of groups, based on a questionnaire; in 2020, 9,600 companies took part.

Risks

■ Physical

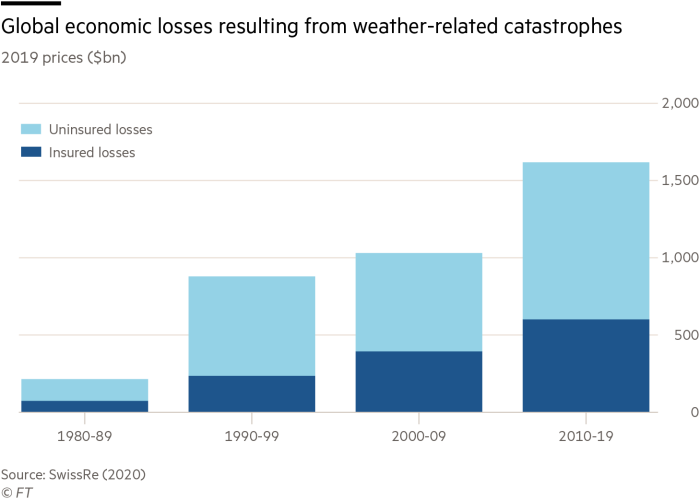

The most tangible risk to assets lies in areas that climate change will directly affect. This includes those that may be submerged as the seas rise, as well as assets affected by the result of extreme weather, including more frequent severe storms, droughts and wildfires.

For existing assets, there are few solutions other than insurance. For new projects the risk must be assessed at conception.

■ Existential

As the shift to a low-carbon world gathers pace, assets in several sectors face obsolescence: they risk becoming stranded assets. Extractors of fossil fuels and the producers of energy sourced from coal, oil and dirty gas are obvious examples.

The risk also applies to areas including the auto industry and aviation. Construction is also affected because of the carbon footprint of concrete and steel. Innovation may create green alternatives but in the meantime producers will have to reduce emissions in existing processes.

Shipping, which accounts for nine-tenths of global freight by volume, is responsible for three per cent of greenhouse-gas emissions, according to Climate Action Tracker. While the International Maritime Organisation has adopted targets, the analysis suggests that action so far is inadequate, with emissions likely to grow.

Carbon offsets are no longer considered a good way to counter emissions. The Science Based Target initiative, which champions defined paths to net-zero emissions, says offsets should not count towards targets as they do not reduce emissions. The consensus is that abatement not offsetting will power the shift to net zero.

■ Transitional

Business models will have to change. Transport, for instance, must shift to zero-emission vehicles. In June, British Gas made the largest UK order of electric vehicles. Volvo has said it will soon have fully-electric lorries on sale.

Emissions from offices also need to be cut. A fifth of UK emissions are from commercial property, so the designers of new projects will have to consider the climate, and old stock will have to be adapted. Schroders highlights innovations in its London premises such as recycling heat from refrigeration to the hot water system, while Freshfields, the law firm, says its move to new premises was made with sustainability in mind.

The Urban Land Institute, a think-tank, says landlords that invested in climate-resilient commercial real estate have reaped dividends. As a result they can charge higher rents to companies that value continuity.

The effect of transition will be felt all the way from company to consumer. Huawei, the Chinese technology group, says its approach is twofold: moving to renewable energy at all of its premises and working to improve energy efficiency and the recycling rates of its products. It says: “These measures often help customers reduce total cost of ownership, creating a strong economic incentive for climate action.”

During the FT Future Forum panel event, UBS said that as well as reducing its own effect on the climate it was making use of capital allocation to bring clients into a low-carbon world. This is significant. Even companies that avoid setting a target will be affected by decisions taken elsewhere. Tesco, among others, has made commitments to reduce emissions in its supply chain, forcing its suppliers into action too.

■ Regulatory

If companies and consumers do not voluntarily work towards low-carbon targets, regulation will force the issue. This could be costly for those late to make the change.

The UN-backed Principles for Responsible Investment forecasts that “abrupt, forceful and disorderly “policy change will come by 2025 and could wipe up to $2.3tn in value from the world’s largest companies. Much of that will be the result of carbon pricing, which Dr Bell describes as “an effective and fair mechanism to rapidly reduce emissions”. Such a system would penalise any company that has failed to reduce emissions to national limits.

“First, companies’ costs will go up because they are now paying for something that they weren’t paying for before”, says Mr Howard. “Second, all of their suppliers’ costs will go up . . . then the price of products will also increase, because ultimately that will be passed on.”

Factoring in a corresponding fall in demand, Schroders concludes that this could eliminate an average 15 per cent of cash flows across companies in the MSCI All Countries World Index.

■ Reputational

Despite these pressures, for many businesses transition may still seem a distant problem. If customers do not appear to care, acting on emissions can look like an unnecessary expense. This is dangerous — and not only because of the high likelihood of carbon taxes. Young people, the consumers of the future, are particularly engaged in the issue and some have run a “Mock COP” in place of the postponed official COP26.

As visible climate offenders such as oil and gas are sidelined, consumers will shift scrutiny to companies in sectors that are thought to be avoiding action. Increased transparency makes it easier to identify lower-carbon alternatives and so empowers consumers in making choices. In September, Amazon introduced a “climate pledge friendly” initiative to flag up sustainable products.

More such data could lead to stranded assets or unviable products in sectors that thought they were safe.

James Hilburn, director of financial services at Carbon Intelligence, believes that the demand for beef and cheese, and out-of-season vegetables, could shrink. “As the carbon emission of these items becomes more transparent and is eventually priced into the product, it may accelerate a market shift away from them.”

In better news for old-world wine drinkers, Mr Hilburn says that “a bottle of wine has an average CO2 footprint of 1.2kg per bottle, but using a natural cork rather than a screw-top can reduce the emissions by a quarter because of the carbon sequestration of the cork tree”.

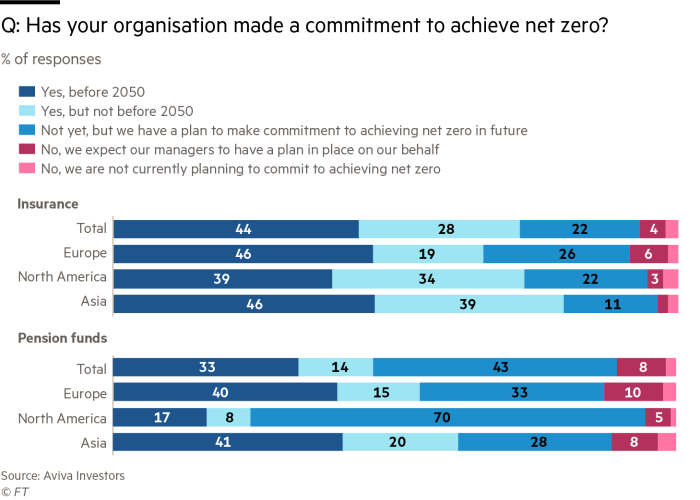

Financing

The role of capital allocators in the climate transition is increasingly important. Mr Hilburn says 60 financial institutions have committed to science-based targets. He says: “The financial sector is seen as the conduit into the market. If you can measure the ESG [environmental, social and governance] implications of capital you can actually flow down to all sectors, and you can achieve change across all sectors. That is really powerful.”

Pension funds, for instance, now invest with climate mitigation and sustainable business in mind. Banks, too, consider climate in their lending practices and direct their equity investments accordingly.

In July the UK’s largest pension fund, the government-backed National Employment Savings Trust, announced that it would divest from fossil fuel exposure. It will not be the last, as climate disclosure under TCFD becomes more common.

Several large banks in the UK and US have signed up to the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials, an initiative backed by Mark Carney, the former Bank of England governor.

Next June the BoE will put financial institutions through a climate stress test, which will make more people and businesses acutely aware of the risks of climate exposure.

The shift of capital is not only driven by ethics. “A growing body of evidence links good ESG performance with superior market returns”, Mr Hilburn points out, “and it comes through a number of factors. You have better cost controls, you have revenue growth opportunities, you have a more engaged, productive workforce.”

In debt funding, the move from projects with a limited shelf-life in a net zero world is feeding into costs. In October Goldman Sachs reckoned that renewables projects could secure funding at 5 per cent or less, versus 20 per cent for long-term oil projects.

Opportunities

Avoiding the downside of delayed action is likely to bring substantial benefits for businesses that move quickly to deploy strategies based on climate mitigation. There are also tangible gains. Mr Carney, who is the UN special envoy for climate action and finance, calls the transition to net zero the “greatest commercial opportunity of our age”.

Technology, for instance, brings opportunities for developers and users. Energy group Iberdrola and technology companies Lenovo and Google have deployed artificial intelligence to enhance efficiencies. The machine-learning solutions that Google created to cool its data centres are being applied to buildings worldwide. Carrefour, the French retailer, used Google AI to analyse large data sets and reduce food waste.

The services sector, including consultancies and legal firms, stands to gain business in advising clients on the best way to achieve net-zero emissions or, in the worst case, how to avoid litigation.

Meanwhile, US juveniles backed by the Children’s Trust were told they had no legal standing to sue their government for jeopardising their futures by ignoring the risks of climate change, although campaign groups such as the Centre for Climate Integrity have highlighted how climate-related costs are borne by communities but polluters are not held to account.

In its 2017 Clean Growth Strategy, the UK identified the low-carbon economy as an area of opportunity. In 2017 it forecast that the sector would expand at 11 per cent a year up to 2030, nearly four times the rate of the broader economy. In the US, the Biden Plan anticipates that millions of jobs will be created in sectors from renewable energy to innovation to low carbon-related construction. Google says its own sustainability investment should generate more than 20,000 jobs in clean energy and associated industries in the next five years.

Meanwhile, UNPRI has a positive outlook for negative emission technologies, or NETs. Just one subset, nature-based technologies, could grow to encompass assets worth $1.2tn, generating annual revenues of $800bn by 2050, larger than the current market capitalisation of the oil and gas sector.

Building Back Greener

Arguably, the coronavirus pandemic has delayed some of the more ambitious plans to invest in green targets. During the panel discussion, Danone acknowledged that its investment in climate change initiatives, announced just before the pandemic, would have to be reviewed since tackling climate change and Covid-19 together was hard.

Dr Bell, however, notes that, against expectation, EY’s survey of investors conducted during the pandemic did not indicate a return to purely alpha generation. “The opposite was true. They said, ‘Nope. It’s far more important for us to focus on ESG now than it has been ever’.”

Nations also look to the low-carbon economy to help beat the economic effect of the pandemic. In June, Germany allocated €40bn of its €130bn stimulus plan to green spending. The Just Transition Fund was introduced a year ago to aid EU economies in the move to low carbon. Its funds will assist the recovery based on low-carbon principles.

Next Steps

The imperative for business to act now should be evident. While setting targets is critical, giving the problem appropriate significance and creating structures to ensure execution are also key to success.

Danone exemplifies what consultants such as EY and PwC advocate in terms of placing climate and sustainability at the heart of strategy. In 2008 the company shut its corporate social responsibility department — an acknowledgment that such issues belong in a broader agenda — and pegged the bonuses of 15,000 managers to CO2 targets.

The FT Future Forum event distilled a three-point action plan for companies to deliver transformation: listen to your customer or clients, engage the full executive team and consult employees, especially the next generation of leaders who are impatient for reform and will leave if they do not see change.

Placing ownership of climate strategy at the right level is critical. PwC is not alone in recommending that this should rest with the board and then be communicated to the organisation using clear targets.

Conclusion

A huge amount of work lies ahead. A recent analysis of 6,000 groups by J Safra Sarasin, the Swiss bank, showed that their emissions were on track for 3.5C to 4C warming, double the level set in Paris.

Dr Bell believes 2030 will be the critical moment, because that is the date that most countries’ nationally determined contributions should be met.

“We see a crunch coming, partly from the investor community — inadvertently. We know a number of leading investors seek to align their investment portfolios to a 1.5C outcome, or to net zero, by 2050.

“Given that we haven’t seen mass divestments yet, you could predict that if companies don’t pivot their business models and start to decarbonise in line with that 1.5C or 2C, there’s going to be this crunch point when investors say, ‘We need to move our funds’.”

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here

Comments