In charts: healthcare technology in low-income countries

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Healthcare in developing countries is far from being universally accessible. Healthcare spending by governments in low-income countries was just $23 per person in 2016, even after adjusting for the relative cost of living, compared with more than $4,000 in OECD member states.

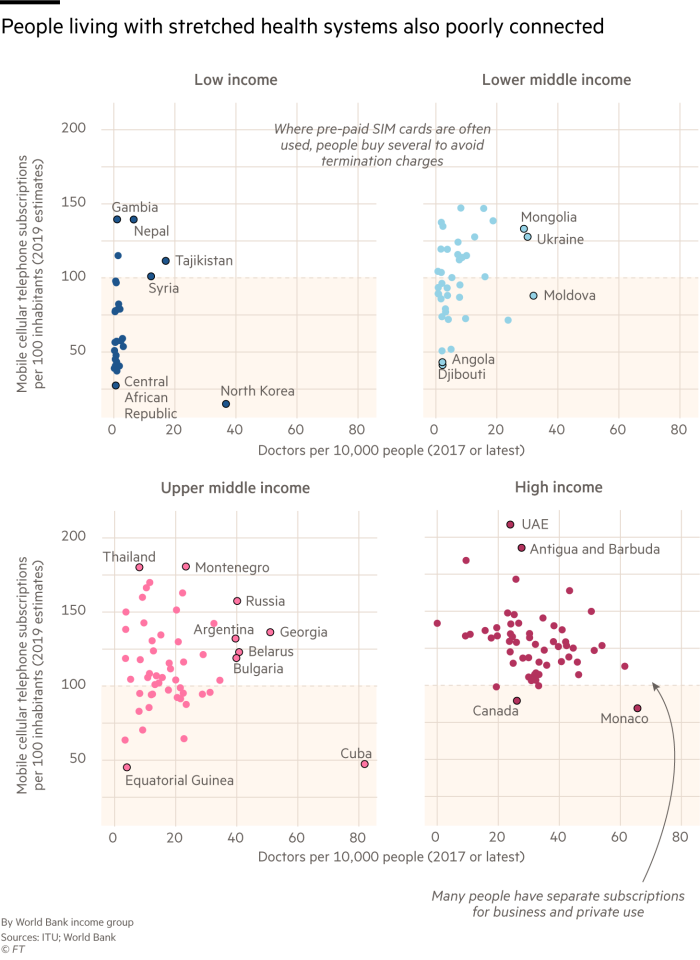

A lack of funding results in a shortage of resources, while doctors are stretched to meet the needs of a large number of patients. In many countries of sub-Saharan Africa there is not even one doctor for every 10,000 patients; in the UK, there are 28.

“There can be a lot of challenges with getting highly trained [medical] people into rural settings,” says Gina Lagomarsino, president and chief executive of Results for Development, a non-profit organisation. “Most want to be in a big city where their kids can go to a good school.”

Technology can help reduce the pressure on doctors and free up resources. Medical call centres, for example, have taken advantage of the fourfold increase in mobile phone subscriptions in developing countries over the past decade and a half. Patients speak to an operator with basic clinical training, who is supported by an AI decision-making system. If the case is urgent or complex, the individual can be directed to the relevant facility. Otherwise, the call centres can recommend basic treatments which can be accessed at home or a pharmacy.

This approach was adopted by Babylon when setting up health services in Rwanda, in partnership with the government. Babylon’s call centres in Kigali deal with 3,000 patients a day, and while its workers are based in the capital, 70 per cent of its users are outside the city.

Tracey McNeil, Babylon’s vice-president of clinical governance, says healthcare capacity has been increased by “shifting to triage being done by machine learning, by chatbots”. But countries with low doctor-to-patient ratios also have poor mobile phone penetration because devices and mobile data remain unaffordable for many.

In these circumstances patients can be connected via a community health worker. Symptoms and readings such as blood pressure and temperature can be shared electronically with a doctor for a diagnosis. In simple cases, AI systems can make these diagnoses without further intervention, and medication can be dispensed locally. As McNeil puts it: “You’re putting a doctor’s brain into the hands of healthcare workers.”

If these electronic record systems were scaled up and integrated with others to build a complete record of patients and their medical histories, diseases could be more proactively managed at a national level, experts say.

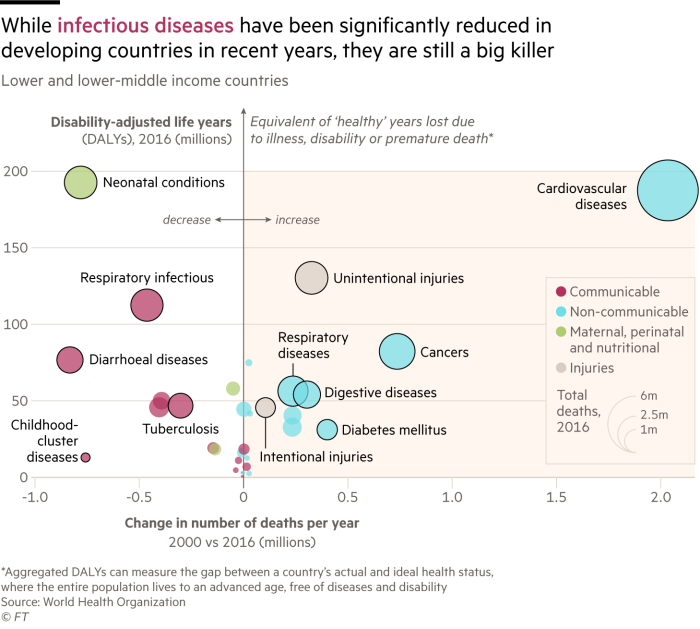

“Suddenly you’re getting real time information on symptoms,” says Lagomarsino. At an aggregated level, this data can highlight flare-ups in infectious diseases such as tuberculosis or respiratory infections, which are still big killers in low-income countries. Treatments can then be better targeted at those in high-risk areas.

Lagomarsino adds: “A strong electronic medical record system is crucial for creating any kind of system of the future for healthcare.”

Comments