UK’s bank challengers are fading in fight with big four

Simply sign up to the UK banks myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The new entrants were supposed to revitalise the UK’s banking market — instead they are looking sick.

Challengers such as Metro Bank, with its colourful American founder Vernon Hill, larger foreign invaders such as Spain’s Santander, under first Emilio Botín and now his daughter Ana, and branchless fintechs such as Monzo, were all supposed to break the dominance of the established big four.

Yet many of the thrusting new competitors are ailing. Last week Santander wiped €1.5bn from the €8.3bn valuation of its UK business — the country’s fifth-biggest bank — blaming increased regulation and the economic impact of Brexit. Earlier in the day, shares in rival Metro Bank plunged 30 per cent after weak demand forced it to pull a planned bond sale.

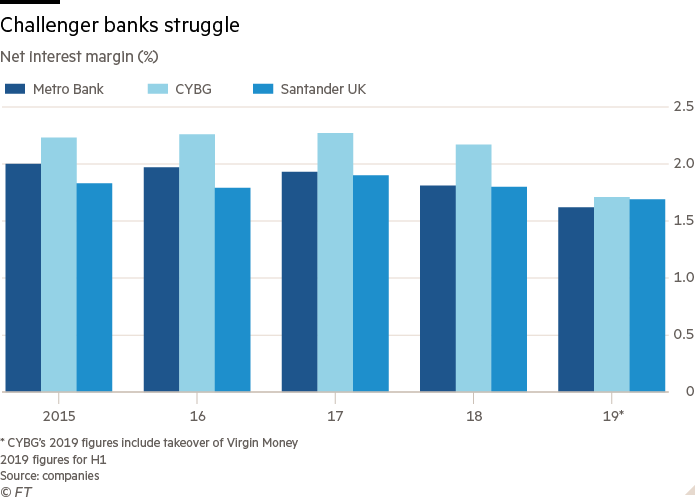

The news capped a terrible September for smaller British banks, which also saw a profit warning from CYBG. The owner of the Clydesdale and Yorkshire Bank brands bought Virgin Money last year to become the UK’s sixth biggest bank, but its shares have fallen by almost 50 per cent since their high in April.

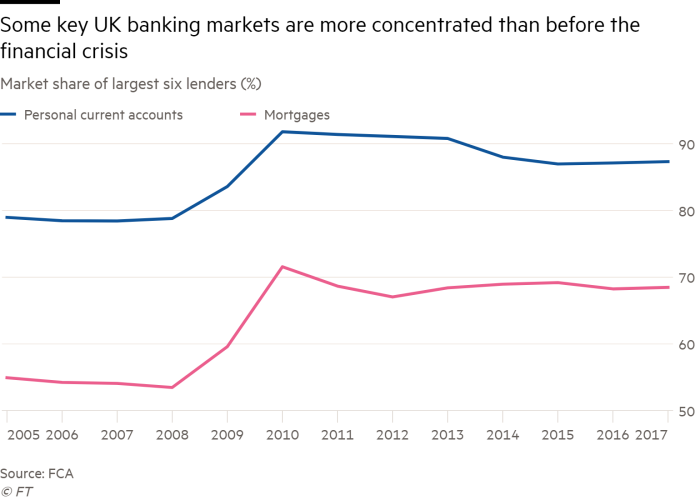

Policymakers had encouraged the new competition to the entrenched Lloyds, Royal Bank of Scotland, and Barclays. It does not seem to be working. In 2000 the top six firms accounted for 80 per cent of personal current accounts, according to the FCA. By 2017, the figure had risen to 87 per cent

Banks say they are not helped by a contradiction in policy. While the Bank of England has offered more than a dozen new banking licences for new firms to get off the ground, it has also introduced uniquely stringent regulations that banks say make it difficult for them to grow.

Lloyd Harris, lead credit portfolio manager at Merian Global Investors, the £25bn asset manager that owns equity and debt from several British and European banks, said: “If you want to promote competition in the sector . . . then you need to make the environment more conducive for them to grow . . . The Bank of England has been quite draconian compared to other parts of the world.”

Metro’s aborted bond sale was supposed to help it meet a new “minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities”, or MREL, which was introduced to prevent a repeat of the 2008 government bailouts.

In the eurozone, a similar requirement to raise expensive loss-absorbing debt applies only to banks with assets over €100bn. In the US, the threshold is $250bn. In the UK, in contrast, the requirement starts at just £15bn, driving up costs even for relatively small lenders.

Challengers have also been hit by “ringfencing”, another set of rules introduced in response to the last financial crisis to insulate retail banks from the risks of investment banking. It applies to any bank with more than £25bn in customer deposits, including retail specialists like Santander. Santander had to legally transfer €25bn of assets from its UK bank to a UK branch of its Spanish parent and duplicate certain functions between the two units as certain types of service for large corporate customers cannot be carried out in the ringfenced UK bank.

Even those that are small enough to escape the ringfencing threshold have suffered: the rules left big lenders such as HSBC with tens of billions of pounds in excess customer deposits that can be used only in the UK. HSBC has piled the cash into the mortgage market, driving down prices and hitting profit margins at rivals.

Individual banks and trade groups such as UK Finance have also been lobbying for regulatory changes to make rules such as MREL more proportionate for smaller banks, but as one adviser to Metro Bank acknowledged, “nothing can be done about it in the short term”. The Bank of England said its primary objective was to ensure banks “are run in a safe and sound manner”, but added that it was listening to industry concerns and taking steps to encourage competition. A spokesperson said: “It’s natural that our work is now moving on to barriers to growth, given the amount we’ve done on barriers to entry.”

In the meantime, all the publicly listed challengers have pledged to significantly cut costs and improve efficiency, and some observers predict the market will see more consolidation.

After last week’s share price drop, analysts have singled out Metro Bank as a takeover target, and an executive at one private-equity owned lender predicted there would be a broader increase in private equity activity once firms have more clarity on the outcome of Brexit.

Metro’s advisers are also hoping an end to political uncertainty would make it easier to carry on alone. The bank plans to try again to raise debt before the end of the year, when it can give more evidence that its performance has stabilised.

Yet it is too easy to blame regulators for the challengers’ woes, many of which are the results of unforced errors. Most notably, Metro Bank revealed an error that hit its capital levels at the start of the year, leading to a capital raise and regulatory investigations. Critics have also questioned its longer-term strategy of building an expensive network of large physical branches at a time when most larger rivals are looking to close theirs in favour of online options.

CYBG’s problems have been less profound, but it was criticised for making particularly optimistic forecasts on the likely impact of a deadline for complaints over payment protection insurance.

Alasdair McKinnon, manager the Scottish Investment Trust, a FTSE 250 investment trust that owns stakes in RBS and several foreign banks, said falling share prices could create some opportunities for investors but, with the sector out of favour and Brexit still to unfold, it would be imprudent to opt for “the riskier and riskier options”. “You want to be in the ones that will definitely survive the cycle and participate in the upside,” he said.

Mr Harris of Merion said: “There needs to be a premium that we’re being paid to be in UK banks. That’s the reality of the situation at the moment . . . we need to be paid because there are other things we can buy.”

Nevertheless, some industry figures remained optimistic on challengers’ prospects.

Richard Davies, chief operating officer at Revolut, said his digital bank’s low-cost approach would prove hardier than the incumbents’. “It’s extremely hard to pivot out of a branch and mortgage-centric model into a digital payments model — impossible even.”

Many of the other “neobanks” are trying to build business models less reliant on traditional lending and therefore less exposed to low interest rates. Revenues will come from recurring fees for premium services such as insurance and stock trading, or commissions for recommending products from third-party partners.

Their branchless, app-based models also help to limit costs and make it easier to expand into new markets. The model has proved popular so far, with rapid customer growth putting further pressure on incumbents and the original challenger banks.

Phillip Monks, chief executive of Aldermore, a specialist lender, said: “It’s clearly evident the challenger bank experiment hasn’t succeeded yet, but I wouldn’t say it has failed . . . I think there are some things in the landscape that give confidence the experiment can work.”

Letter in response to this article:

Ringfencing was a bad idea — abandon it now / From Peter D Hahn, London, UK

Comments