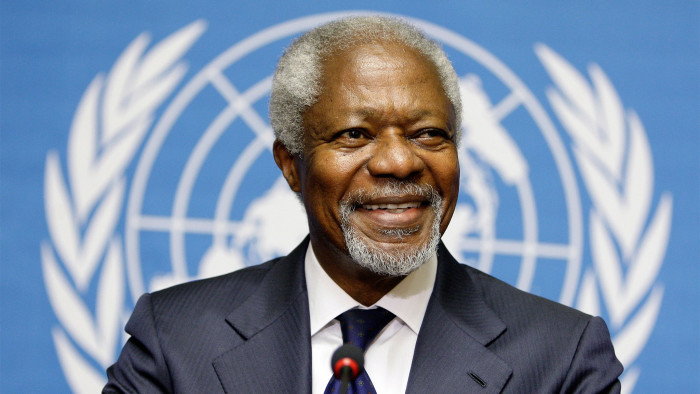

Leadership lesson from Kofi Annan

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Kofi Annan offers up the first lesson in leadership. In business, diplomacy and life, “Knowledge is power. Information is liberating. Education is the premise of progress in every society, in every family.”

At first blush, Annan seems far from the imposing figure he struck during his 10-year service as secretary-general of the UN. In person, the 2001 Nobel Peace Prize winner is engaging, full of humour and self-effacing. But you don’t have to listen to him for long to realise that he understands the challenges, responsibilities and opportunities of leadership at a very deep level.

I met Annan in 2012, when he came to Vancouver to speak to students at the University of British Columbia’s Sauder School of Business about his career and the lessons that have come along with it.

Born in 1938, Annan came of age in the late 1950s just as his homeland, formerly known as the Gold Coast, was gaining independence from Britain as the new state of Ghana. It was, he says, a time “when suddenly you realise that change is possible”. It was also the first time that ethnic Ghanaians began to take over the formal leadership roles in his country – and thus a particularly important time for a generation of young people to attain the education that would help ensure that “change” would be synonymous with “progress”.

Annan’s own education took him through a series of institutions, culminating in MIT’s Sloan School of Management. His first job as a lowly budget officer in the World Health Organisation, started a diplomatic career that would take him to the highest levels. Yet even then, he understood that leadership arises not from the position you’re in, but from the actions you take. Everyone, at every level and in every organisation can show leadership by proactively identifying problems and finding solutions.

The first part – identifying problems – takes a degree of vision and even more courage. And in the roles Annan filled, it took compassion and a conviction that “suffering anywhere concerns people everywhere”. That is what inspired him to take on a challenge that delivered one of his greatest successes – the battle against HIV/Aids in the developing world. In 2001, when he called for the creation of an international global “war chest” of $5bn to fight the disease, he says, “Everybody thought that I was dreaming. I said, ‘That’s fine. I’ll keep dreaming’.” He raised many times that amount, in a battle that transformed the lives of millions of people with HIV/Aids.

On the way to that success, Annan also demonstrated a second essential element of leadership: having the vision to identify a problem, you then need the ability, the commitment and the drive to find creative solutions and to implement them. This also requires some pragmatism, some realpolitik determination. Or, as Annan says, “If you are a dreamer, one thing that you need is to know when you are awake and when you are sleeping.”

One of Annan’s other lessons has obvious appeal for the business school community. It arose early in his career from what we might think of now as an environmental scan.

“One of the key questions I asked when I took over was: ‘What can the UN do?’ ‘What can the UN not do?’ and, ‘What should the UN leave to others to do?’ And that led to the partnership that I saw with business.” At the time, there were those who argued that the international diplomatic community should not be allowing their affairs to become tangled with commercial interests. But Annan recognised the opportunities that could arise from this partnership. “What is important,” he says, “is that business has the resources, skills and, in some cases, energy that the UN could not muster.”

This gets to three components of generative leadership. First, good leaders always have time, or make time, to listen to others – even when the “others” in question may not be on your advisory board or among your usual friends and allies. Second, good leaders trust others to bring solutions. If you try to craft every solution yourself, you can get trapped trying to fix every problem the same way. Or you may just miss some wonderful opportunities. And third, good leaders make space for others to succeed – to bring their skills to bear in solving problems or creating new opportunities.

Given how important education has been in my own career, it is impossible not to bring this back to the opportunity we all have to leverage lessons learned elsewhere – to recognise, as Annan so eloquently says – that “education is the premise of progress”.

——————————————-

Robert Helsley is dean of the UBC’s Sauder School of Business and Grosvenor professor of cities, business economics and public policy. He will answer readers’ questions live on Wednesday between 14.00 and 15.00 BST.

Comments