Gamification at work creates winners and losers

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Even before Covid-19 forced employees to work from home, many businesses were moving to more remote working. While this offers flexibility, autonomy and cost savings, it makes managing staff more challenging. Without frequent face-to-face contact, organisations need to become more creative in their approaches.

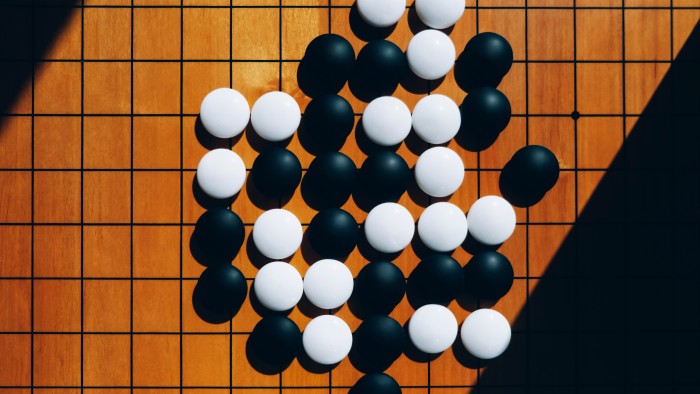

One option is the use of a fast-growing technique for motivating and managing employees. Gamification is the process of introducing design elements from games into other contexts. Advanced computing now gives organisations the ability to track staff behaviour. Programs such as reputation point systems, badges, leader boards ranking staff by performance and online training resembling board games can inject fun into everyday work.

New staff can enter elaborate fantasy worlds to complete training. Sales teams used to working alone on the road may be connected through platforms simulating sports, where a sales lead is as an “assist” and closing a sale is a “goal”. Employees who complete reports can earn points toward achievement badges — reputational signals of their value.

Gamification is part of the human resources strategies of many large businesses, including PwC, Cisco, Deloitte and Ikea. Walmart tested it to raise awareness about safety and cut accidents. In a pilot, when employees played games and earned badges after answering safety questions, incidents fell by 54 per cent.

But do such programs really work? Most research indicates that they increase engagement. For example, multiple studies show that in online communities where members ask questions and answer other people’s queries, they increase activity when awarded reputation points and badges. Online communities have similarities to remote work, with geographically dispersed members interacting.

Despite such benefits, researchers know less about the potential dark side of gamification. For example, many programmes digitally record and publicly display information about employees, so unexpected negative consequences may arise if they overly intensify pressures for performance and competition between staff. Research in psychology and organisational studies shows a link between performance pressures and reduced willingness to help and share information with others and an increased likelihood of lying, cheating and even sabotage of others’ work.

In a recent study of more than 6,500 online community members’ data spanning nine years of activity, I explored the unintended negative consequences of a reputation system. Members earn reputation points for contributing questions and answers. More valuable contributions, as rated by members, earn more points. To discourage negative behaviour, members who exhibit counterproductive behaviour such as spamming for commercial gain or being excessively impolite are temporarily suspended.

I found that counterproductive behaviours increased when a member was near a reputation threshold — a key point before gaining extra benefits and prestige. This suggests that such systems — and by extension other gamification programs — can cause negative consequences.

Do these unintended negative outcomes undermine the goal of increasing engagement? When I compared members who were suspended for counterproductive behaviours with others, I found they contributed more than their average amount when engaged in counterproductive behaviours.

Psychological theories of moral cleansing explain that employees generally want to maintain a positive image that they are good citizens. Engaging in counterproductive behaviours threatens that image, so it prompts employees to contribute more often to make up for these practices.

Jointly, these findings suggest that reputation systems — and gamification more broadly — can be effective in maintaining employee engagement in remote-work environments. But managers should be on the lookout for unintended consequences that may arise with increased competition and performance pressures.

Employees take it upon themselves to correct for these behaviours, reducing concerns about their ultimate impact. Other forms of gamification could trigger more negative unintended consequences, however. In particular, the use of leader boards and contests that confine rewards to a small, select group of employees can trigger unhealthy levels of competition and more pernicious behaviours such as sabotage.

Unrelenting performance pressures can lead to higher levels of burnout, so managers need to actively assess employees’ reactions to gamification. Periodic use of anonymous surveys that track sentiments about helping others, job satisfaction and engagement could serve as early warning signs of gamification’s unintended consequences.

The widespread popularity of gamification programs suggests they are here to stay. Initial research confirms they can positively boost employee engagement, especially if staff have a choice in how they use them and if they are designed to align with the organisation’s goals. It is clear, however, that managers must remain vigilant about the potential downsides of increased competition and the performance pressures that accompany them.

Cassandra Chambers is assistant professor of management and technology at Bocconi University, Milan

Comments