Austerity dilutes effort to combat pandemics

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When leading industrial nations at the UN pledged fresh support to tackle some of the world’s most lethal infections last month, two nations stood back.

That hesitancy — by Italy and the UK — to provide more money to the Global Fund to Fight Aids, TB and Malaria, which supports prevention, diagnosis and treatment in poorer countries, was a signal of the difficulties ahead in tackling existing and emerging communicable diseases.

The coronavirus pandemic is estimated to have killed at least 16mn people globally, left millions more with debilitating illness, and wreaked lasting economic damage. It continues to claim lives every day, and should be a sobering reminder of the resurgent risks of infection alongside the underlying — and interrelated — growth in non-communicable diseases.

But, despite pledges to learn the lessons of Covid-19, caution is already waning. And recent reminders of the need for vigilance are failing to have the impact they warrant. They include growing antimicrobial drug resistance, outbreaks of Ebola in Africa, cholera in Haiti, and polio and monkeypox in the US and other developed countries.

Nina Schwalbe, adjunct assistant professor at Columbia University’s Mailman school of public health, says that, during the UN general assembly in New York, where the Global Fund’s replenishment took place: “You got a feeling almost that Covid never happened. At the UN, people were slammed together in the elevators and the pandemic was not a core part of the debate.”

Against a backdrop of waning engagement, she argues for a system to build resilience against future pandemics overseen by heads of government to ensure accountability.

“It’s remarkable that we went through Covid and didn’t come out with better data systems or better access to preventive healthcare,” she says. “I don’t get a sense from what we’re seeing from polio or monkeypox that we’ve really learned any lessons.”

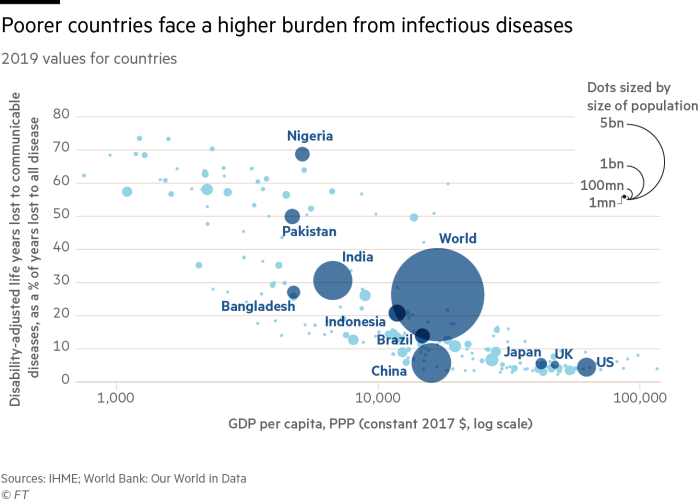

There is, however, still willingness to provide financial support. Peter Sands, head of the Global Fund, says that, in spite of hesitancy from a few large donors, the $14bn pledged in September suggests “there is clear recognition in both a moral priority to save lives and a self-interested priority to contain infectious diseases and preserve socio-economic stability”. He adds: “It’s very difficult for countries and communities to prosper and thrive if they are under a very heavy disease burden.”

Technological advances have been made since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, with implications for other less severe infections. There is fresh investment in vaccines, and the application of mRNA technology provides scope for a range of more effective, targeted and rapid ways to shield against illness and death.

But far less progress has been made in establishing better funding, procurement and distribution systems to ensure more equal global access to vaccines. Without such progress, the risks remain of a continued cycle of mutation and a return of pandemic diseases in developed countries.

Hans Kluge, regional director for Europe at the World Health Organization, argues there has nonetheless been promising recent political momentum, including strengthened international health regulations and continued reflection on a future pandemic agreement.

He also cites a pledge by countries to provide more core funding to his agency, as well as a new pandemic fund being developed under the auspices of the World Bank.

Yet, as the most visible effects of coronavirus fade, nationalistic attitudes in some countries — combined with belt-tightening amid an economic slowdown — mean many policymakers are turning their attention elsewhere.

Broader issues that help fuel the spread of communicable diseases remain poorly addressed, such as global warming and deforestation, and some may be competing for the same funding.

For example, a recent commission convened by medical journal The Lancet on the pandemic concluded that policymakers must do more to regulate the trade in domestic and wild animals that spread infection to humans. But pandemic issues must fight for attention. The Rockefeller Foundation recently folded its Pandemic Prevention Institute into its wider activities, with its head departing the organisation.

Government austerity also risks diluting efforts around disease prevention, from measures to reduce salt and sugar in food to broader programmes designed to limit cardiovascular diseases and other underlying conditions that made many vulnerable to other illnesses, such as Covid.

Like many of his peers, Sands stresses the prime importance of strengthening existing health systems to tackle communicable and non-communicable diseases alike.

“The priority should be to fight existing big disease threats — and do it in a smarter way that explicitly builds in multi-pathogen capability and surge capacity,” he says.

Kluge agrees. One of his greatest concerns is the current stress on healthcare systems around the world, as workers retire or burn out and quit, while the pipeline of replacements is thin.

“The health and care workforce is a ticking time-bomb,” he says. “There is a medical desert. But we have to invest in the health workforce and reserve capacity. We see the battle is not won in hospitals, it’s won in primary healthcare.”

Comments