Profound risks lurk despite strength of economic rebound

Simply sign up to the Coronavirus economic impact myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

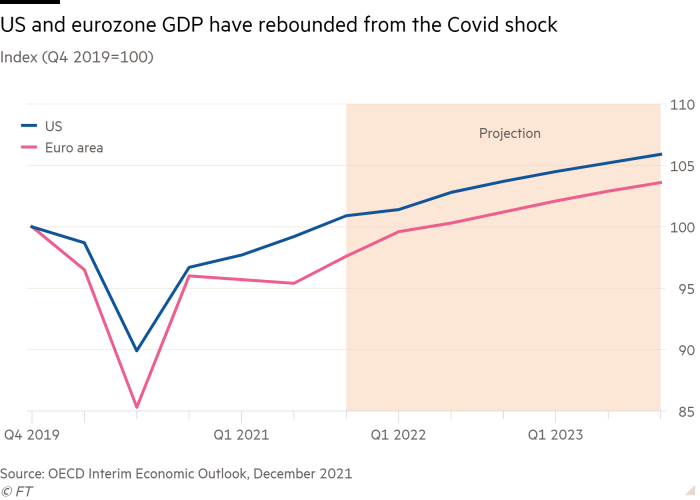

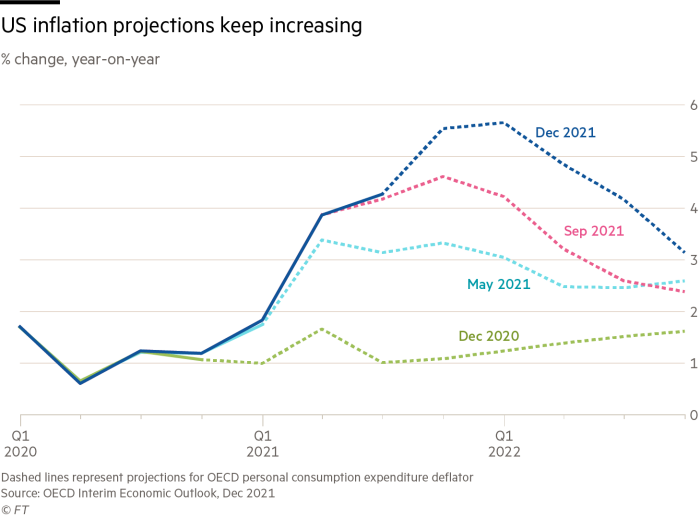

The big economic surprise of 2021 was the strength of the economic recovery. Another was the surge in inflation that accompanied this recovery, particularly in the US. After the shock from Covid-19 in 2020 and the unexpectedly strong recovery and inflationary surprise of 2021, what might 2022 have in store for us?

The most recent OECD forecast is of global growth of 4.5 per cent in 2022, only modestly below the recovery-boosted growth of 5.6 per cent in the previous year. The OECD also forecasts 4.3 per cent growth for the eurozone in 2022, against 3.7 per cent for the US, but inflation of 4.4 per cent in the US in 2022 against 2.7 per cent in the eurozone.

One can imagine upside risks, even relative to this reasonably attractive scenario.

Inflation might disappear more quickly than forecast, for example, if the supply shortages that accompanied the recovery are remedied. This would then allow central banks to persist with monetary accommodation.

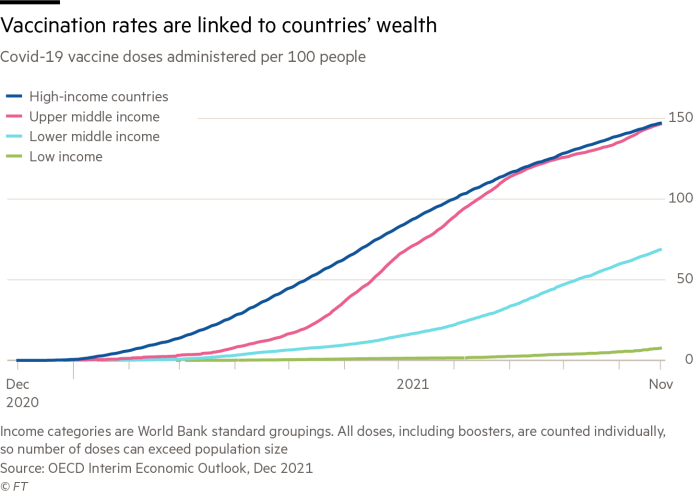

In addition, further coronavirus variants, beyond Omicron, might prove progressively less harmful. Or a worldwide vaccination programme might give enduring respite from the pandemic. If so, a faster reopening of the world economy could support a still stronger and more widely shared recovery, especially in the economies of badly damaged emerging and developing countries.

Yet there are also downside risks, both economic and non-economic. Among the former is the possibility that the surge in inflation continues to surprise on the upside, possibly generating a wage-price spiral as workers respond to the damaging effect of high inflation on real wages. That might uproot the anchor for inflationary expectations.

Central banks would be forced to tighten far more fiercely than currently expected. This would almost certainly also generate negative reactions in today’s frothy asset markets, possibly causing a wave of bankruptcies.

Among the non-economic downside risks is the emergence of coronavirus variants against which current vaccines are ineffective. There are also geopolitical risks, most obviously the tensions between the US, China and Russia. Such tensions have frequently been realised as wars.

Other risks fall at the interface between economic and non-economic. One is substantial damage to global economic relations as the friction between China and the West continues to worsen, as now seems likely.

Then there is the longer-term danger of destabilising climate change. While awareness of the threat is growing, action is still well behind what is needed to avoid potentially catastrophic shifts in the climate. The recent COP26 climate conference in Glasgow was not a total failure. But it was also far from a success. If Donald Trump or someone like him becomes the next US president, the chances of dealing successfully with this threat would become vanishingly small.

The big lesson we have learned over the past one and a half decades is just how uncertain the world economy is. We can recognise a few predictable forces: the inbuilt tendency of market-driven economies to grow, the continuation of scientific and technological advances, and the demographic forces of fertility and ageing. But there are also unpredictable drivers of disorder: financial crises, political upheavals, geopolitical stresses, pandemics and, in the background, climate change.

Covid-19 has reminded us forcefully of such uncertainties. It has also brought with it some powerful lessons. Among these, two stand out.

The first is that, in the context of such pervasive uncertainty, it is vital for our systems to be robust, or resilient, or a bit of both.

Robust systems can function throughout shocks, while resilient ones return swiftly to normal functioning after such shocks. Which one we need depends on how vital continued operation is. In general, systems that supply vital goods and services, such as basic foodstuffs, medical supplies, energy or day-to-day financial services, need to be robust. But users of many other goods and services can cope with some disruption. In that case, it is resilience that matters.

Both businesses and policymakers need to decide where they need robustness and where they need resilience — and how much they are prepared to pay for either and in what way. But they should also avoid the obviously mistaken view that “local” is a synonym for “robust” or “resilient”. Putting all one’s eggs in the basket named “local” guarantees neither robustness nor resilience.

The second and far more important lesson is that the contradiction between the species we are and the world we have created is becoming ever more dangerous. Although an intensely tribal species, we have created a global world.

Covid has been a global shock par excellence. Yet it has proved impossible to mount a coherent global response, above all in the supply and delivery of vaccines. Such tribalism has ended up increasing the vulnerability of everybody. Similarly, geopolitics is pulling the world apart, even though it is more integrated than ever before on multiple dimensions, not least economic ones.

This contradiction between who we are and what we have built is the dominant one of our era. These stresses may not shake the foundations of our world in any given year. But they create background risks that should not be ignored.

Comments