Anthony Hopkins: ‘Act as if it is impossible to fail’

Simply sign up to the Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

As Anthony Hopkins wins the Oscar for best actor in The Father, we revisit an interview with the multi-award winning actor first published last autumn. The film will be in UK cinemas from 11 June.

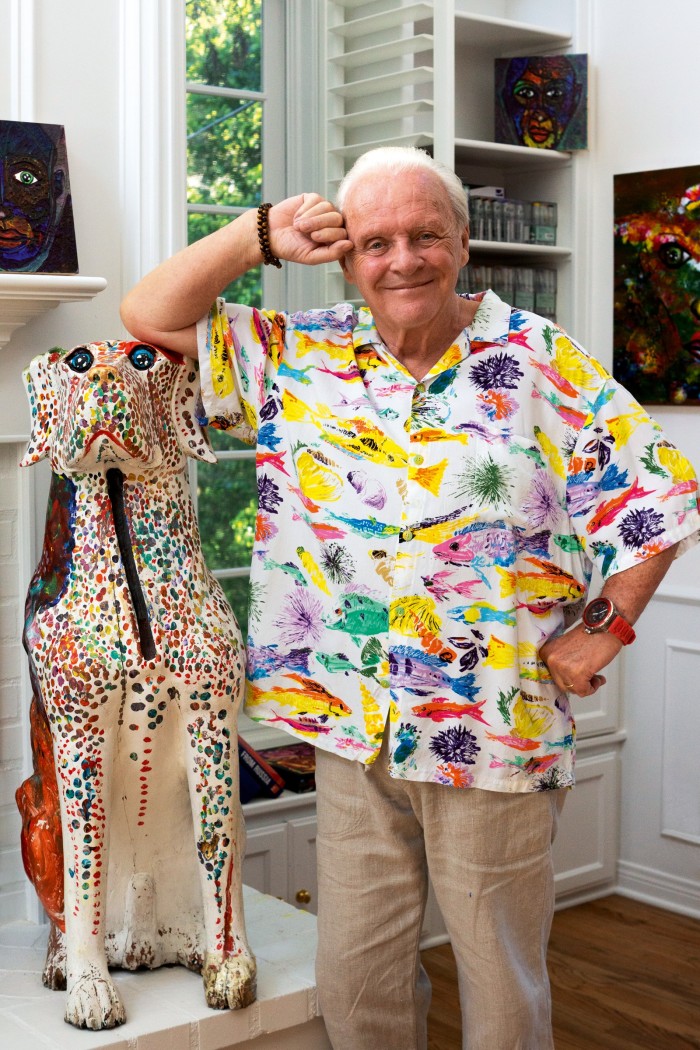

Anyone who has been following Anthony Hopkins on Instagram of late will have been treated to a ringside view of his many faces. There’s been the soulful Hopkins playing the piano to his cat Niblo in his Malibu home; the goofy Hopkins doing the Drake dance from TikTok; the mimic doing Sly Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger accents; the wearer of many wild and colourful Hawaiian shirts.

But perhaps most of all there’s been the inspirational and the philosophical Hopkins – calling out to the younger generation that, despite everything going on at the moment, they can make their dreams come true (back in July he posted this: “Congratulations to the class of 2020… I read somewhere, I can’t remember whether it was in the Old Testament, or I think it was a shaman, and the shaman said – there was a drought, cattle were dying, people were dying in the desert – and the shaman said, build the ditches… Dig the ditches and the rain will come”).

It’s many decades since Hopkins, now 82, shed his hard-drinking, hell-raising skin, but he’s still an inscrutable customer, and the flash of mercurial danger remains. That danger has defined him as an actor – you never know what, or whom, you are going to get next, whether he’s playing King Lear on stage at the National Theatre or winning an Oscar for his portrayal of the serial killer Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs. Back in 1973 he walked out of a production of Macbeth mid-run; two years later he had his last drink. He’s gone on to be one of Hollywood’s most prolific stars, earning four more Oscar nominations for The Remains of the Day, Nixon, Amistad and, this year, The Two Popes. His story could have been one of talent squandered, but is one of redemption. And it’s definitely the wise old statesman in mellifluous south Welsh voice who speaks to me from Malibu rather than the anti-hero with a sinister whisper or an ear-splitting bark.

He gives me the whole motivational nine yards. “That post about the class of 2020, I was thinking how devastating it can be for a whole generation of young people starting out and suddenly their teacher is gone. I mean, what’s going to happen? So that’s where my idea came from, because the story of my life was to believe and visualise a powerful outcome. I act as if everything is possible. I act as if I believe. Even if sometimes, you know, you always have doubts, but when the doubts come, just push through and believe that it’s going to work. Act as if it is impossible to fail.”

In the past he’s said he’s not sure what he believes in from one day to the next (“God or Santa Claus or Tinker Bell”). Today, he seems to have resolved that whatever force there is, it comes from within. “I’ve survived all these years, despite my doubts and my past, I’m constantly surprised and I think it’s been down to a kind of – these are powerful words – but faith or belief in some kind of energy that we possess in us. I’m not a psychiatrist, I’m not a philosopher, I’m none of those things, but… it’s something that maybe I tapped into when I was a young kid. And I’m sure I believe it can happen with young kids today. Believe in it, believe and see yourself into a powerful future.”

His concern for the younger generation has resulted in a somewhat incongruous (for those of us who can never forget him as the liver-eating Hannibal Lecter) but nevertheless admirable project. He is releasing an Anthony Hopkins brand of perfumed candles and diffusers and an eau de parfum (inspired by the scents of the countryside of his childhood in Margam near Port Talbot in south Wales) to support the No Kid Hungry campaign started by the charity Share Our Strength. “We’d been working on it for about a year and then lockdown changed the course of events and this idea came up about the immense hardships that have hit families throughout the world, especially kids not being able to go back to school. It’s a devastating thing that has happened and all I can do is offer a vision of positivity that people can come through this.”

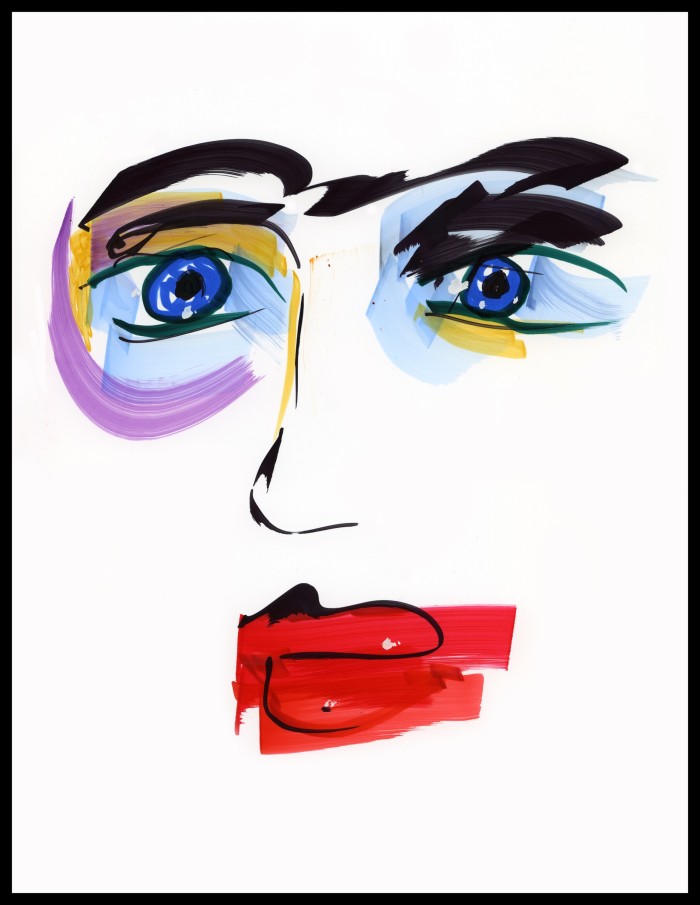

The packaging will feature Hopkins’ own paintings, because in addition to being one of the hardest-working actors in Hollywood, he is an artist of some renown, not to mention a composer whose works have been recorded and performed live on stage by the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. He may be, as Richard Attenborough once had it, the greatest actor of his generation, but it turns out that treading the boards was something of an afterthought in the mind of the young Hopkins.

Music was his first love and he would improvise tunes on the piano as a child. “I wanted to be a pianist and all that,” he says, “and by sheer fluke and accident I became an actor.” He also loved to draw as a child and toyed with the idea of becoming a cartoonist. Not for very long though. “I met a man from the Western Mail who was himself an artist and cartoonist and he said, ‘Ah, it takes great skill’, so I ditched that idea…”

It took him half a century to pick up his paints again, encouraged by his third wife, Stella Arroyave, who had seen the doodles he would draw on his film scripts. “She’s the powerhouse,” he says. “She saw my drawings and said ‘You ought to paint – just do it.’ The same with music. She heard me playing a piece of music and said, ‘What is that?’ And I said, ‘I don’t know, just something I made up hundreds of years ago. And she said, ‘Well, you ought to do something with it.’ So I got it orchestrated and she sent the manuscript to André Rieu and he played it and I started composing more.”

Many of his paintings are haunting expressionist pieces in which eyes feature large, staring with Hopkins-esque fire from the depths of the canvases. They are a swirl of neon colours, the paint slathered on like thick paste. There are also landscapes, some Hopper-esque, others more impressionistic. “I’m not good at being instructed and I couldn’t sit in an art class drawing an apple,” he says. “At the start I thought, ‘I can’t paint.’ But another voice said, ‘Well, just have a go at it, nobody’s going to put you in jail if it doesn’t work.’”

One painting, Ballet on the Moon, features a menagerie of animals, including a pink elephant with flirty eyelashes, gathered around an old man’s head, perhaps a reference to an outing he had with his grandfather to the circus in Port Talbot in 1947. It’s a moment in time that is also evoked in one of his musical compositions, as his working-class childhood in Margam returns again and again as an inspiration in his work. He grew up a single child, the son of a baker. His father was a no-nonsense man who taught him to keep his feet on the ground. His mother encouraged his musical side, buying him a £5 cottage piano. One of his paintings shows a pair of Port Talbot steel workers, their heads Munch-like ovals, walking side by side, while the pastoral counterpoint of that industrial landscape is evoked in a tenderly nostalgic orchestral composition named, simply, Margam. “I’m conscious of my past every day,” says Hopkins. “I dream that I’m back there a lot of the time. I spent some time there last year, doing a documentary on my time in Wales and toyed with the idea of maybe returning.”

It would be a long journey back to a place where, at school at least, he was not happy; he traces many of the issues that troubled him as a younger man to that time. “When I was a kid in school I wasn’t very bright,” he says. “I was regarded as rather backward and so, of course, at the age of adolescence I felt very angry and confused and I didn’t know which way to go. I didn’t seem to have any hope at all. And I remember saying to my father, ‘One day I’ll show you.’ I remember that, it was Easter 1955, and I said it with such conviction to my father, who always encouraged me, by the way. I said it because my school reports were appalling. ‘One day,’ I said, ‘I’ll show you.’ And I remember by the end of that year I got a scholarship to the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama and within 10 years extraordinary things happened in my life. I still look back today and wonder how any of this happened. I think it came from that one signal moment.”

Of course, there were setbacks along the way. He tells a story of travelling from Wales to the Old Vic for an audition in 1960 and being told by the director, “Ah, you know, maybe one day, but I don’t think you’ve got it now.” Twenty years later the same director came to Hopkins’ dressing room when he was playing a monstrous newspaper magnate in David Hare’s Pravda at the National Theatre and ate humble pie. “So that’s the way it goes,” says Hopkins blithely.

By 1965, he had been invited to join the National Theatre Company by Laurence Olivier. Young and ambitious, he quickly stole the limelight. In his autobiography, Olivier remembers having to hand over the part of Edgar in Strindberg’s The Dance of Death to Hopkins because he had appendicitis: “A new young actor in the company of exceptional promise named Anthony Hopkins was understudying me and walked away with the part of Edgar like a cat with a mouse between its teeth.”

Hopkins recalls that period, and later working with David Hare on Pravda at the National in 1986, as his two happiest times in the theatre. But the mid-1980s also marked his swansong as a stage actor. His last Shakespearean performance came in 1986, playing King Lear directed by Hare. Hollywood was calling. Peter Hall, then director of the National, lamented, “We got the last of Tony’s Shakespeare, and it’s very sad he stopped.”

Does he regret walking away from the theatre? “I just felt I couldn’t hack it. I couldn’t do the routine. I mean, I wasn’t a socially adept person. I thought, ‘I don’t fit in yet.’ Then circumstances changed and I came to America and made Silence of the Lambs and that changed my direction a little and I thought, ‘Maybe you should stick to this.’”

Would he ever consider coming back to the stage? “I worked with Ian McKellen five years ago on the film The Dresser. I do admire him and Judi Dench and all those people who have that tenacity, that drive to go on stage. I, sadly, unfortunately… maybe I’m too nervous to expose that part of myself. I don’t think I’ve got that staying power, I don’t think I have that mettle in me to be repetitive night after night. No, I have no desire to go back there. Unless there was an extraordinary offer – and I’d have to think twice.”

David Hare once told Hopkins that he was the most angry person he’d ever met. And in a Southbank documentary broadcast at the time he and Hopkins were working on King Lear in 1986, Hopkins said, “[Lear’s rage is] so volcanic… it cracks him wide open… I have that rage.” Where did that inner rage come from and how has he learned to master it?

“I think it was just… going back to that little kid, being unstable, feeling like a misfit… It wasn’t particularly volcanic rage or anger of that kind. It was just an energy… I just called it an energy, an energy of not fitting in. You can’t waste your time being enraged all the time because life’s too short and it’s going to kill you. So I’ve just been lucky I’ve survived all these years and, yeah, I’ve had two lives… I look back sometimes on my life 40 years ago and think, my God, what a mess that was. I’m not proud of my past. I wouldn’t have missed it, that’s the way it was for me. But I’m not proud of things I did. I did cause a bit of damage. A couple of people I worked with just died, they snuffed it because they destroyed their own lives. No, I was on that course as well and I thought, ‘Thank God I got out of it.’ I’m not an evangelist. I’m not a preacher. I’m glad I got free of that nightmare because it was not pleasant. I wasn’t a very nice guy, I was a pretty ugly guy. So over the years I thought ‘Calm down, calm down.’ I’m just very lucky to be here.”

The risk of catching Covid-19, he says, has meant he has had to turn down a role in a film with Kenneth Branagh (“one of my favourite actors”). But he’s still riding a high after being nominated for the best supporting actor Oscar for The Two Popes, and his wife has just directed him in a film she wrote, Elyse (streaming from 4 December), where he plays a psychiatrist helping a young woman who has had a mental breakdown. Also out in December is the film of Florian Zeller’s hit play The Father, in which Hopkins is a man sinking into dementia. After the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year, Vanity Fair described it as “a towering piece of acting that is as precise and exacting as it is enveloping. It reminds you why Hopkins enjoys the venerated stature he has had for so long.”

Hopkins himself says, “It’s one of the best films I’ve been involved in. The past five years for me have been great, working with Richard Eyre, Ian McKellen, Emma Thompson and then this one with Olivia Colman. A pretty remarkable time.”

And so on he goes, preparing painstakingly for parts, painting, playing the piano, writing a film script set in Wales, giving a home to rescue cats and dogs, and wearing Hawaiian T-shirts with aplomb (they’re from a shop called Jams World in Hawaii) – a complex mixture of sage and no-bullshit working-class lad from Port Talbot. “Keep smiling, keep having a laugh, that’s all you can do,” he says, as we sign off.

AH Eau de Parfum and home-fragrance collection, anthonyhopkins.com

Comments