Tutankhamun rises again in show looking at ancient Egypt’s cultural legacy

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This year’s centenary of the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb is an enviable opportunity for a fair such as Masterpiece, whose objects span thousands of years of history. For its 11th in-person edition, and the first since 2019, the fair launches a platform called [Re]Discovery, to explore how culture gets reinterpreted over time, and its first project, called Avoiding Oblivion, takes Howard Carter’s 1922 excavation as the hook for looking at more than 500 years of Pharaonic obsession. The show will include Carter’s watercolours and a very 21st-century virtual reality display, incorporating a facsimile of the king’s sarcophagus chamber.

But anyone who expects a Disney-like display of a popular piece of history should think again. The multi-part mini-exhibition is the result of 20 years of work by the Factum Foundation, a non-profit dedicated to preserving and conserving cultural heritage through cutting-edge technology: founder Adam Lowe says the team has around 60 people developing equipment such as scanners and 3D printers. It also boasts a network of artists, conservators and scholarly researchers, including an acoustic archaeologist. Lowe is working on cultural projects in Nigeria, Italy, Spain, the UK and Brazil, while his wife (and partner in the Masterpiece project), Charlotte Skene Catling, runs an award-winning architecture practice.

Their display starts by showing how ancient Egypt had — well before Carter’s discovery — captured imaginations and even generated, millennia after its peak, some squeamish practices. The facade of the exhibition reproduces an image of the 18th-century print “Caffè degli Inglesi” by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, based on his design for the café, complete with pharaohs, hieroglyphs, pyramids and other celebratory images, all imagined by the Italian polymath. “He had never been to Egypt, but this would have chimed with all the Grand Tourists in Rome,” Lowe says.

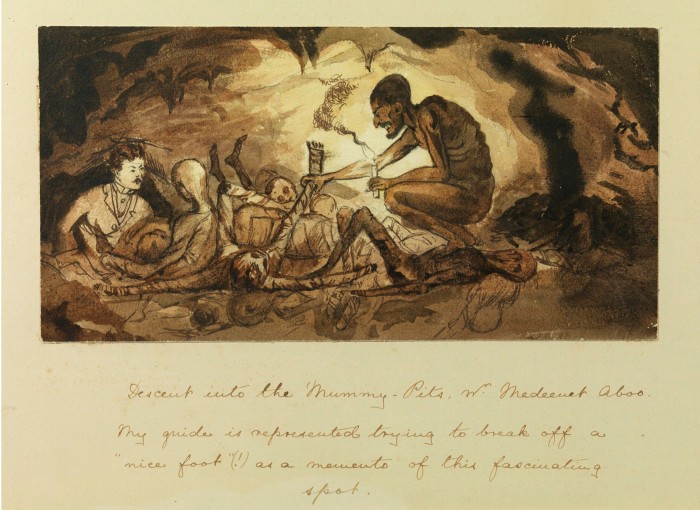

The dubious 17th- and 18th-century practice of eating mummies is unearthed, including photographs of street vendors known as “mummy-sellers”. “The first cannibals were in Europe. They thought that the bitumen [a preservative] was a cure-all and that, coming from the ancient Egyptians, it could confer magic powers,” Lowe says. The Masterpiece display recalls the “mummy unwrapping” parties that were hosted by the Victorian intelligentsia, and it will also have a recreated tube of the paint pigment known as “mummy brown”, made from ground-up mummies and still available to buy until the 1960s.

Facing the entrance to the exhibition will be a large facsimile of a painting known as “The Celestial Cow”, from the tomb of Seti I, who reigned from about 1290BC to 1279BC. This heralds a deeper meaning to the project. The richly decorated tomb was found “immaculately intact” by Giovanni Belzoni in 1817, Lowe says, and to record his findings, the Italian explorer made plaster casts of the walls of the tomb — an action that removed layers of the original paint.

Much of our understanding now of what “The Celestial Cow” looked like comes instead from a watercolour that Belzoni made with his assistant Alessandro Ricci. “In the name of preservation, he destroyed the tomb. That’s the conceit of the exhibition,” Lowe says. He holds back any criticism of such acts though. “Belzoni’s intentions are the same as ours today. Don’t assume that what we are doing is any better.”

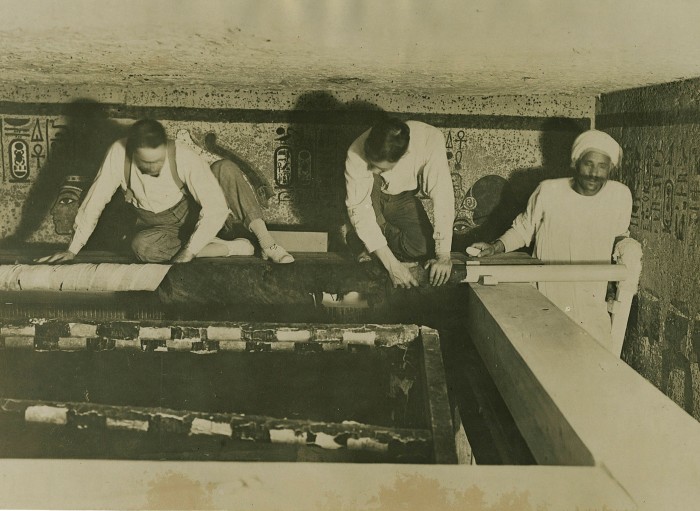

The hope is, of course, that it is. Lowe’s work so far, including in the Valley of the Kings with the far-sighted collaboration of Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, has made significant steps towards what he describes as “sustainable tourism”. In 2012, Factum completed an exact physical facsimile of Tutankhamun’s tomb, installed in the Valley’s visitor centre since 2014.

Lowe explains: “Tutankhamun’s [real] tomb was receiving about 1,000 visitors a day. The room heats up, cools down, there’s humidity and dust, pressure points on its very fabric. Is it better to see a tomb that was built to last an eternity — but not made to be visited — or to see a facsimile? We need a new approach [to originality], which involves preserving the natural order to avoid oblivion.”

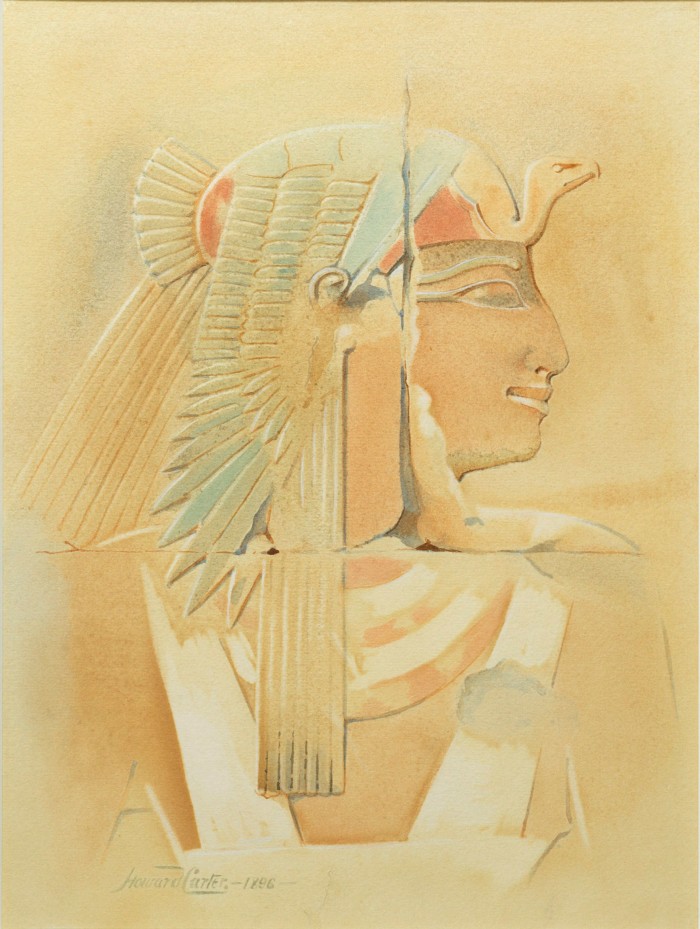

Lowe’s ambitions run deep at a time of climate change and its associated problems. But there is plenty in his Masterpiece presentation to please those who visit simply as Tutankhamun obsessives. On show will be 14 watercolours made by Howard Carter during his travels, with subjects including the wall paintings and objects found inside tombs.

“He was not one of the best artists in the world, but was one of the greatest observers, with a beautiful quality of line,” Lowe says. He highlights one painting, “Under the Protection of the Gods” (1908), that combines Carter’s passions for ornithology and Egyptology: he depicted a hoopoe bird observed from life in front of a vulture painted on the wall at Deir el-Bahri. The display has 51 first-hand photographs taken by Harry Burton, who joined Carter in Egypt and whose work has proved crucial to our understanding of the excavations.

The watercolours and photographs come from the private collection of the 20th-century sculpture dealer Rupert Wace, but nothing in the exhibition is for sale, even in the middle of an art fair. “People can spend many hours in Masterpiece, but this is an opportunity for them to switch off [from its commerce]. They could go for a glass of wine, go to a restaurant or pop into this exhibition and really look,” Lowe says.

He plays down the virtual reality display, which will project what viewers see through their headsets on to the wall behind the facsimile tomb. “VR can be tricky in a public place as only a couple of people can do it at a time. But it is an experimental way to see if we can show another world through the eyes of others,” he says.

There is yet another level to Avoiding Oblivion: the project was suggested by Philip Hewat-Jaboor, Masterpiece’s visionary and erudite chair who died after a brief illness earlier this year. Lowe says: “The display is about the continuation of what is important, so it now takes on a new meaning as it never occurred to me that Philip wouldn’t be there to see it. This is our tribute to him.”

June 30-July 6, masterpiecefair.com

factumfoundation.org

Comments