Annie Morris on her passion for pigment and finding solace in art

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In its art-deco heyday it was the Painter’s Room, then for years a storeroom — a passage going nowhere. Now this forgotten space at Claridge’s hotel in London has re-emerged as a chichi little bar. On either side of a bright, blue and turquoise stained-glass window, playful drawings line the walls, including a bird wearing a hat and a female figure whose head is a daisy — all the creations of Annie Morris.

Sometimes upright, sometimes reclining, this figure pops up everywhere in the British artist’s drawings, tapestries and sculpture. “She started as a self-portrait many years ago,” Morris says, when we meet during the installation of her work at London’s Timothy Taylor gallery. “Now she’s a quick way of putting myself in the picture.”

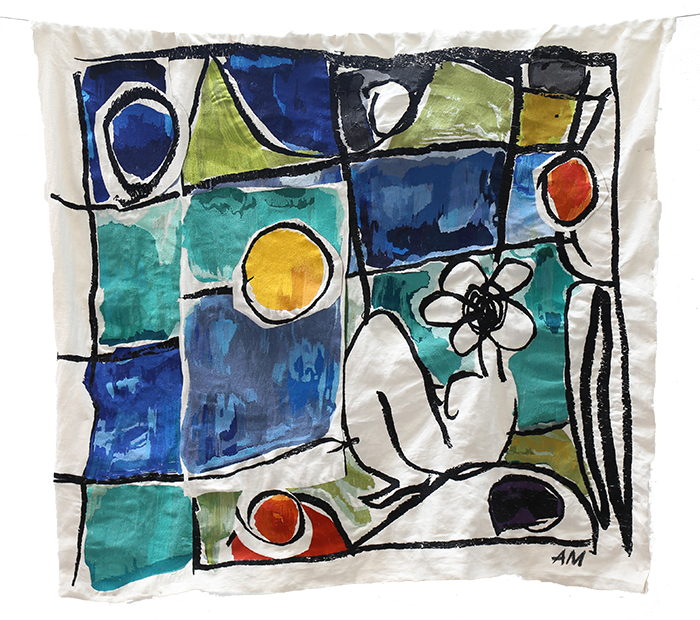

Morris, 43, has been busy. In addition to the newly unveiled bar and the Timothy Taylor show, which includes recent sculptural experiments and “Woman with a Moon” (2021), the tapestry on which the Claridge’s stained-glass is based, she has a piece in Frieze Sculpture in Regent’s Park. Meanwhile, her first solo show in a UK museum has just opened at Yorkshire Sculpture Park (YSP).

For YSP’s When a Happy Thing Falls, Morris has assembled an immersive installation of “stacks” — fabulously coloured, precariously balanced towers of wonky spheres and egg shapes — that jostle together in the park’s Weston Gallery.

These towers are testament to the artist’s passion for pigment. There is a work or two in bronze, but most are carved “balls” of pigmented plaster. In applying their intense ultramarine, viridian, ochre or turquoise, Morris has long sought the impossible: “To freeze the moment before paint dries.” The paint does dry, of course, but her aim is to leave “a surface that is soft and velvety, very much like pigment in its raw form”.

In their riotous colour, the stacks convey pure joy. But seek out Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem that provides the title — “And we, who have always thought/ of happiness as rising, would feel/ the emotions that almost overwhelm us/ whenever a happy thing falls” — and you may not be surprised to learn that the first of these sculptures were born of grief. Back in 2012, Morris found solace in drawing, needlework and the repetitive action of carving the misshapen spheres while grieving for her stillborn first child.

Though abstract works, the towers are rooted in the figurative: the flower-woman. At YSP, two small tapestries hang alongside the stacks, each one depicting a woman lost in a mop of unkempt hair. Look closely at these women and you notice some tiny splashes of colour above them, marks — made unconsciously at the time — that gradually became Morris’s route out of misery and a way into an apparently infinite game of experimentation in form and colour. “I was looking at those little coloured marks and feeling comforted by them,” she says.

At the same time, she had a “desperate” urge to create the bulging pregnant shapes that now epitomise the stacks. “That’s where it all started: this feeling of ‘let’s make that shape and let’s make these little lines come to life in these towers’.”

After a foundation course at Central Saint Martins, Morris enrolled in a BA at the École des Beaux-Arts, Paris, in 1997 before returning to do a masters at the Slade. And what a moment to be at the Beaux-Arts: Annette Messager, Christian Boltanski and Richard Deacon all had studios there. With Giuseppe Penone as her tutor, she poured linseed oil on canvas, flung pigment at it then carved into the colour — much as Jean Dubuffet might have done, she says. But it was sculpture rather than painting — or some hybrid of the two — that fired her imagination: “In sculpture, you looked at how paint reacted to plaster. I was fascinated by the process and by what I could do to make paint do things I didn’t know if it was possible to do!”

Over nine years, the stacks have changed their meaning. No longer therapy, no longer bound up in grief, they continue to probe the possibilities of form and colour. At Timothy Taylor, an intensely blue tower — an exercise in deconstructing the colour — greets you at the entrance, while next door a massive orb in cadmium red, her largest sculpture to date, tops a three-ball stack. This magnificent red has an echo in a dangerously tilted tower at YSP, evoking for Morris a kinship between her stacks and Barbara Hepworth’s finely balanced “Family of Man”. Several have been acquired by the Fondation Louis Vuitton, but back in her studio, stacks surround her: “They are protective. I love looking up at them.”

For Morris these days, stack-making is a joyous obsession. Earlier works deployed thousands of clothes pegs, then came assemblages of postcards. An affinity for repetition, she suggests, is part of her make-up. And she delights in the fact that in every act of repetition, there is difference: “Even when you do five drawings that are all the same, there is always one that sings.”

‘Annie Morris’, Timothy Taylor gallery, to November 13, timothytaylor.com. ‘When a Happy Thing Falls’, Yorkshire Sculpture Park to February 6, 2022, ysp.org. Frieze Sculpture, Regent’s Park, London, to October 31, frieze.com

Comments