Julian Schnabel: an audience with the ‘master’

Simply sign up to the Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Just after Donald Trump lost the US presidential election, and as he grew obstinate in his refusal to concede, the artist Julian Schnabel turned his attention to two things: a new series of flower paintings (bold pink buds and green leaves, painted over crockery, a glimmer of optimistic blue sky showing through) and a concession speech for the soon-to-be ex-president to deliver, which he emailed to Trump’s daughter Ivanka.

Schnabel reads it to me on FaceTime. “I would like to take this historic and momentous occasion to right things as much as I can,” it goes. “I can’t bring back those we have lost due to the pandemic or those who have suffered because of my decisions. But I can make this right by asking the 70 million people who voted for me to embrace the brightness of this day and help Joe Biden and Kamala Harris in the difficult obstacles to come in fixing our magnificent country.” The speech, Schnabel theorises, “could have saved some lives”. Ivanka, to his chagrin, did not reply.

The self-belief required to pivot from artist to unsolicited political speechwriter is typical of Schnabel, a man who has built a career on the conviction that he can do anything, and do it better than anyone else. He has made paintings. He has made sculptures. He has written books. He has directed films, including The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, which won two Golden Globes, and the recent van Gogh biopic At Eternity’s Gate, starring Willem Dafoe.

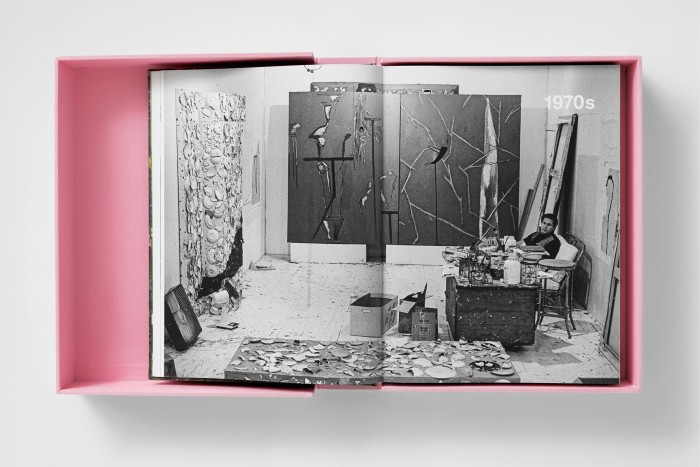

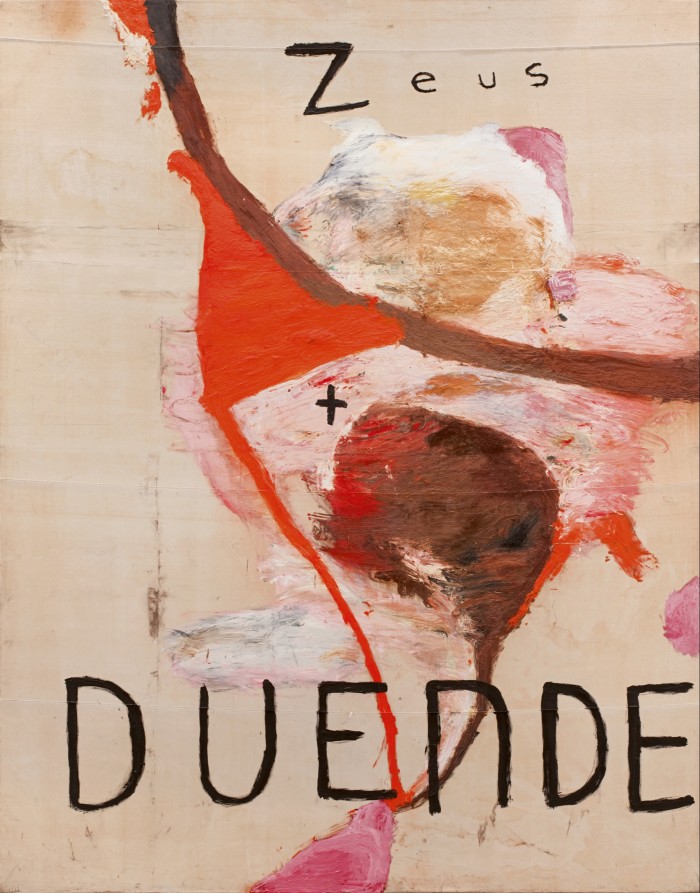

All of these achievements have been brought together in a new monograph, published by Taschen, which is enormous (44cm x 33cm) and costs £750. It is a fitting partnership between a publisher that correlates scale with significance, and an artist whose obsession with size is so renowned it has almost become a performance, a parody of the male ego. A Schnabel canvas – one of his signature plate paintings, full of thick, gorgeously gloopy layers of pigment, or a work rendered over used tarpaulin, found in a Mexican fruit market – can come in at over 6m, and he has hung them on the outside of buildings in order to accommodate the scale. As well as enormity, Schnabel’s art tends to build upon found materials as its starting point, taking things that have a history of their own before they become part of the painting. Hence the crockery, or the sheeting, some of which was studio material first – say, used to cover a painting – and became a canvas later. Over this come gestural brushstrokes, or figures, often icons, or wording. Schnabel is interested in how the meaning of symbols can shift or disappear when context is changed; he has made paintings based on the images from psychological tests, or navigational charts, or the letters of different languages.

The book has a cover of roses and comes in a weighty pink box that acts as a protective case, surrounding it like a frame when opened. The pink gives the artworks an aura, producing, in Schnabel’s words, a “halo around every painting, which goes perfectly with every page”. Schnabel has a taste for the godly, for anything transcending mere mortality. The titles of his paintings refer to saints and angels as often as they do celebrity subjects and famous artists. A week or so before our interview, he was at his studio in Montauk, painting outside in the cold, without a coat. “I don’t feel cold. You just forget about your body, you forget about everything somehow,” he says. In 1977 Schnabel called a work I Don’t Want to be King, I Want to be Pope.

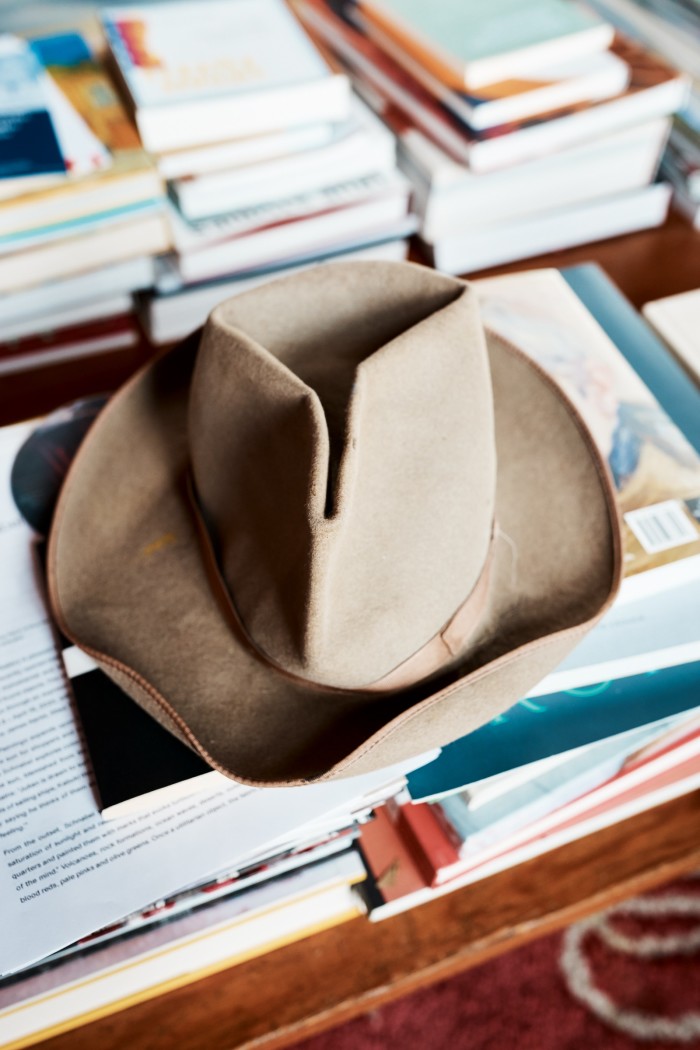

Schnabel’s bombastic nature is legendary. The size code of “XXL” given to the book by Taschen could be applied to the artist himself. Almost no interview with him is published without a reference to his 1992 comment, made to a journalist from New York magazine, “I’m the closest thing to Picasso that you’ll see in this fucking life”, which he later said was a joke. Certainly, he enjoys bragging – he is great fun to talk to: boisterous, unbridled, at points playfully self-aware, at others deliciously oblivious. At several moments during our conversation, he gets so wrapped in his own stories, or in regaling long passages from his films, that he loses the point of his reference and pauses for long enough that I wonder if our FaceTime connection has dropped. Usually he gets back on track – buoyed by a sea of names to drop: Blinky Palermo, Lou Reed, “Bob” Rauschenberg. At one point, he instructs me to reread his 1987 book CVJ, part autobiography, part gossip, part analysis of the cliques of power within the art world. “Cy Twombly once said, ‘I read it twice. I wish I wrote that book’,” Schnabel tells me.

Schnabel is often described as “controversial”. He explains, in a roundabout way, that people are likely just jealous. “When I started to show with Leo Castelli, I was the first artist that he took into the gallery in 12 years. There are a lot of young artists who want to be seen. If somebody takes that slot, people get pissed off about it.” Schnabel also professes disdain for the US art landscape. “I felt like The Whitney Museum of American Art was almost like folk art. I mean, art is meant to break the boundaries down between borders. So I encouraged international art – Italian artists, German artists. That changed things. And a lot of people get displaced or get out of work in these shifts of culture.” These shifts happen in the art world every decade or so, he says. There was a time for abstract expressionism, then pop art, then minimalism, then conceptual art. New styles emerge, people fade into irrelevance, and some emerge as the big cheeses, the puppeteers of the mood. “And if you can find a person to be the emblem of this, for bad or for worse, then I guess I maybe wore that on my shoulder.”

Today, the “controversial” tag is, I’d argue, less and less about art-world wrangling and ever increasingly about Schnabel’s personhood, and the narrative framework he has carved out. Some of it is affected and cliched – the partying; the wearing of pyjamas to important events; the erection of a colossal pink home, based on a Venetian palace, in New York City, which he refers to as Palazzo Chupi. And some of it is innate: his maleness, his whiteness, and his confidence, the innateness of which is, of course, impossible to separate from the maleness and the whiteness. Schnabel has, to borrow his own words, become a new kind of “emblem” of a certain art-world figure that many see as a symbol for the problematic habits and hierarchies of the entire industry. He is a “master”, an artist with a capital A, an ’80s poster boy for glitz and wealth and braggadocio.

The book is beautiful – but it is also, to some extent, a defence. A massive retort to his critics in the past, with gushing pull quotes, from Schnabel himself and curators including Norman Rosenthal and Rudi Fuchs. “After Schnabel, anything is possible”, writes art historian Bonnie Clearwater in a stunning example of hyperbole. “I’ve read so many crummy things about myself and my work. It’s nice to see that there were some good things that were written,” Schnabel says.

But, more than an attempt to thumb his nose at doubters of the past, the book can be read as a justification, a case, against the new guard of the day: those who might say that Schnabel is, or very soon will be, an artist of the past. The book’s press materials claim that Schnabel is “synonymous with the return of painting to new relevance”. But a critic might say that the obsession Schnabel shares with certain older, often male, artists in the canon of painting – in creating “a painting that has never been made before”, as Schnabel has declared – is barely radical. Are there not higher stakes than battling with past masters?

Schnabel is exhausted by the growing focus on the moral weight of art and the current insistence that art be political, questioning, “necessary”, to quote the trending word among critics. “I don’t think that art is discursive,” he says. His art is about something less tangible, something less explicit than activism, he continues. He refers me back to the book, and for me to read aloud a quote by Max Hollein, now director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Schnabel’s works become receivers for a poetry that is both personal and universal. In his case, intentionally painting the unknowable yields a more faithful representation of experience than any attempt to realistically depict the physical world ever could.” “That last part is pretty good, right?” Schnabel says. To Schnabel, this is a defence against the idea that art should argue. “Describing something doesn’t necessarily solve it. Making something that has some kind of parallel equanimity to that thing, in and of the form, is probably more useful.”

Still, the mood is the mood, he shrugs. “Some art is opportunistic. Some art is pandering to what the social climate is at the time. I think that these waves of politicism do impair the vision of people. And they buy things because they fit into that envelope.” He pauses. “I made a painting in 1979 called Circumnavigating the Sea of Shit. Well, that’s what we’ve got to do.”

Schnabel is operating in a world where the foundations underpinning his generation’s power are cracking, where the internet has amplified previously unheard voices, and where power can no longer be a buffer against accusation. All this irritates him. “It’s an absolute crime for people to criticise someone like Dana Schutz for making a picture of Emmett Till,” he tells me, of the controversy around the white artist’s painting of a 14-year-old boy who was lynched by two white men in Mississippi in 1955. “This is just a white person who has empathy for a black person. I don’t think that you need to be black to appreciate black people.”

He attempts to shrug off a recent article that described him as the archetype of a “white artist”, but seems troubled: “Look in the book and there is a picture of Muhammad Ali and me and Olmo [Schnabel’s son] when he was a baby. I mean, if I’m a racist then you could pick on anybody and point your finger at them and say whatever. It’s kind of pathetic.” But, he adds, “If I were a black lesbian, I think it would be easier for me to have a show at the Met now.”

Schnabel’s refusal to be bogged down in his own potential limitations has buoyed him through the pandemic. He has realised, he tells me, that he doesn’t actually care much if people see his work. Last year, one of his shows at Pace, New York opened on 5 March and closed a week later due to the lockdown. Barely anyone saw it, but it didn’t matter to him. “When you’re younger, that would drive you crazy, but now I can just make the paintings and see what they look like and put them the way that I think they should be seen. I don’t even really need an audience.” He has opened shows since, with the Pace exhibition transferring to a different location in September, and another at his son Vito’s gallery in Switzerland in December, but he is nonplussed about reactions. “I made the paintings and I saw what they looked like. I don’t need more.”

He has always been terrified of death, he tells me, but increasingly he’s feeling calm about it, and about his legacy, about future interpretations of his art and of him, the artist. “The book is a very good barometer for that. I can see what I did. And I’m not ashamed of what I did,” he says. “I could die tomorrow and it would be fine.”

In the meantime, he is bunkering down with those who know and love him. He keeps plenty of his own work close, hung on the walls at home, where his skill is applauded and where he can reflect on the past, when those who mattered got him, when they were all on the same page. The crowd doesn’t affect him now, he insists. As a young man he felt “an emotional and a personal need for other people. Maybe you get to a point when you need them less and less, and maybe you are speaking to people who are dead.”

Letter in response to this article:

Comments