Growth, reform and ECB support are crucial to Italian debt sustainability

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

There are two ways of talking about Italy’s public debt. One is to say that it appears shockingly high and will surely pose a threat, sooner or later, to the stability of the 19-nation eurozone. The other is to say that what matters is not the debt’s size but the cost of servicing it — and, measured by that yardstick, Italy poses virtually no threat at all.

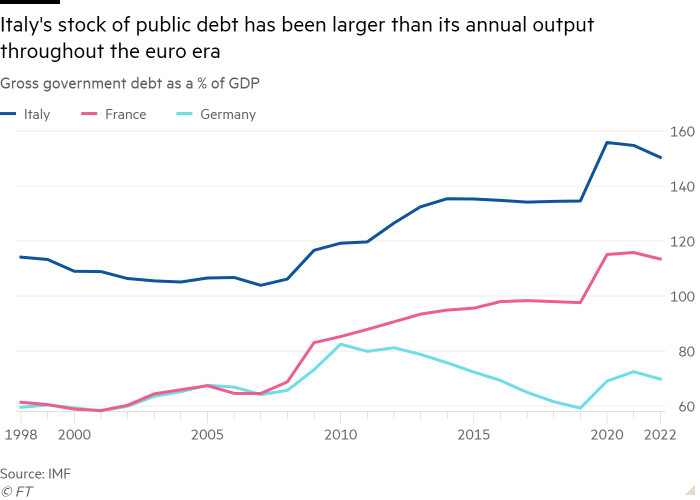

Indisputably, Italy’s public debt is extremely high. According to Italian central bank data, published on February 15, the debt amounted to almost €2.7tn at the end of 2021, or slightly more than 150 per cent of gross domestic product.

When the euro was launched in 1999, Italy’s public debt was 113 per cent of GDP. Earlier in the 1990s, EU leaders said a country could not join the currency union unless its public debt was 60 per cent or less of GDP — or, if it was above that level, it was supposed to be going down in a satisfactory manner.

Yet the lowest level Italy’s public debt has touched in the euro era is 103.9 per cent of GDP in 2007. Since then, it has gone up and up. If Italy were outside the eurozone and wanted to join now, would it meet the criteria?

Paradoxically, as Italy’s debt has ballooned in size, it has become more manageable. Particularly over the past two years, the crucial factor has been European Central Bank support. From March 2020 to the end of last year, the ECB bought some €250bn of Italian debt under its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme.

Partly as a result, the average interest rate paid on Italian sovereign debt fell from 6 per cent in 2020 to 2.4 per cent last year, according to Frederik Ducrozet of Pictet bank. Moreover, Italy has reduced refinancing risks by increasing its average debt maturity to 7.6 years — about the same as the eurozone average. “It would take a large and permanent shift higher in bond yields to drive average interest payments to ‘unsustainable’ levels,” says Ducrozet.

Still, financial markets remain hypersensitive to all the complex issues surrounding Italian public debt. At the start of the pandemic, Italian bond yields rose sharply after Christine Lagarde, the ECB president, said it was not the central bank’s job “to close spreads” between the borrowing costs of eurozone countries.

She quickly walked back that remark, but the market turbulence underscored the connection that investors see between Italian debt sustainability and ECB policy measures. This was evident once more in early February when the ECB signalled that it might raise interest rates in response to inflationary pressures. Italian 10-year bond yields rose briefly to a 21-month high of 2 per cent.

For markets to be reassured that Italian debt will not pose a risk to eurozone stability, the ECB will have to take great care about the timing and scale of any rate increases and withdrawal of asset purchase programmes. It will need to show markets that it will not tolerate financial fragmentation of the kind that splintered the eurozone in 2011-2012.

At the same time, Italy has immense responsibilities of its own. Its public debt would concern markets less but for the fact that, for more than two decades, Italy has been the eurozone’s laggard in economic growth. One essential condition for sustained growth is a political climate conducive to economic reforms, moreover, which do not remain on paper but are actually implemented.

Here the outlook is mixed. Preliminary data put Italian economic growth last year at 6.4 per cent, the fastest rate since 1995. Yet in January Italy’s central bank published some fairly cautious estimates of GDP growth over the next three years — 3.8 per cent this year, 2.5 per cent in 2023 and 1.7 per cent in 2024.

Even these growth rates will depend to an extent on whether Italy makes good use of the €200bn in grants and loans available from the EU’s recovery fund. This has been the focus of the reform initiatives of Mario Draghi, Italy’s prime minister, during his year in power. He aims to make the reforms irreversible so that, even if he leaves office after Italy’s 2023 parliamentary elections, no future government will make a mess of them.

Despite a promising start, not all is going Draghi’s way. Earlier this month, Italy’s rightwing parties pushed an amendment through parliament, against the wishes of Draghi’s government, that raises the limit for conducting transactions purely in cash to €2,000 from €1,000. The lower limit had been introduced to clamp down on illegality and the black economy.

As this episode shows, it matters greatly who will govern Italy after Draghi and how reform-minded will they be. It is hardly surprising that the markets are still twitchy about Italian public debt.

tony.barber@ft.com

Comments