Christian Louboutin: trapezes, tiger skin and pretending to be Kissinger

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

To move around the Parisian apartment of Christian Louboutin, 55, is to embark on a journey that takes you from Damascene palaces and French cabarets to the inner power circles of the UN, where the boundaries between the shoe designer’s international adventures and the rich streams of his imagination are indistinct.

We meet in early July during Paris Haute Couture Week, in which Louboutin unveiled a collection of made-to-measure designs that included gold-plated soles for knee-high embroidered sneakers and a matt black alligator pump with hand-sculpted gold-plated wood spikes. Louboutin’s signature design is a towering stiletto with red-lacquered soles, which has become a celebrity staple. “I have the objects disease,” says Louboutin. “I don’t buy clothes; I really buy objects.”

Louboutin moved into the apartment 10 years ago after spending two years renovating it. He says wanted the apartment to look like a 1930s gym studio and even sought to install trapeze bars on the ceiling, to practise this unusual pastime, but the ceiling wasn’t quite high enough. “I like very much the 1930s and 1940s in terms of decor for movies,” says Louboutin, who was inspired by the kind of apartment that actress Marlene Dietrich had in the 1944 Arabian Nights-style film Kismet.

The only visible nod to Louboutin’s career as a shoe designer is a set of three large photographs on the wall next to the kitchen, part of a series by film-maker David Lynch, who was inspired by Louboutin’s designs.

We sit down at a black lacquered coffee table and Louboutin explains his philosophy of buying objects on his travels. “I’m always thinking hand luggage,” he says. “But often I have to check in my luggage, and after that it’s ‘oh my God it’s too heavy’ . . . and then it’s a container issue.”

He concedes that the huge coffee table “doesn’t scream hand luggage”. (It was shipped from Los Angeles in a container.) Louboutin flicks a switch and the sides of the table pop out. “The table seems very conference room, you know: [former US secretary of state Henry] Kissinger, United Nations. When I’m sitting at this table I feel like I’m Kissinger, in the UN, taking care of what’s going to happen in the next 50 years around the world.”

The apartment is on the top floor, up four floors in the lift and then a spiral staircase. Along a balcony overlooking the spiral staircase are adjustable shutters, fashioned on those of Islamic architecture which allow people inside the house to observe without being seen. The windows are a take on Ben Hur, the 1959 epic film, says Louboutin.

Louboutin was born and raised in Paris. He dropped out of school and began sketching shoes in his early teens, inspired by his visits to cabaret music halls such as the Folies Bergère. “I was interested to design shoes for showgirls — that was really my obsession,” he says. “I was really fascinated by the way women were dancing, and everything that was super-frivolous.”

Louboutin had grown up believing he might be adopted, given that his skin tone was darker than that of his three sisters, and then four years ago, after both his parents had died, he discovered that his biological father, whom he never met, was his mother’s Egyptian lover. “I was quite surprised . . . and at the same time I was not surprised at all,” says Louboutin. “I always had a huge thing for Egypt.”

Louboutin began working in fashion, first for designer Charles Jourdan, and then as an apprentice in the atelier of Roger Vivier, who claims to have invented the stiletto. He went on to work as a freelance designer, creating shoes for well-known houses including Chanel and Yves Saint Laurent. A two-year stint as a landscape gardener followed in the late 1980s before he set up his eponymous Christian Louboutin company in 1991 and opened a store in Paris.

Louboutin may now be synonymous with red-lacquered soles but these came about by accident. One day he was comparing his colourful shoe sketches with the 3D prototypes. “Something was better, stronger on the drawing than on the real shoes, where there was a big black sole,” says Louboutin. “I noticed that the proportion of black was very strong, and this was not existing on my design.” A girl who had been trying on the shoes all day had stopped and was painting her nails red. “I grabbed her nail polish and started to paint the sole. Immediately, it popped exactly like my drawing.” The rest is fashion history. “At the beginning I didn’t necessarily think of keeping the red soles. I never thought of trademarking them. I just thought it looked beautiful.” Today, Christian Louboutin regularly turns to legal action to defend its signature red soles and last month the brand won a decisive victory in the European Court of Justice in an intellectual property case relating to them.

Among other items collected from his travels is the centrepiece around which the colours of the apartment were co-ordinated: a marble floor in terracotta, black and white that was once a fountain in a Damascus palace. Louboutin bought it in Belgium at a fair. “It was very important that piece because I love it in terms of colours.”

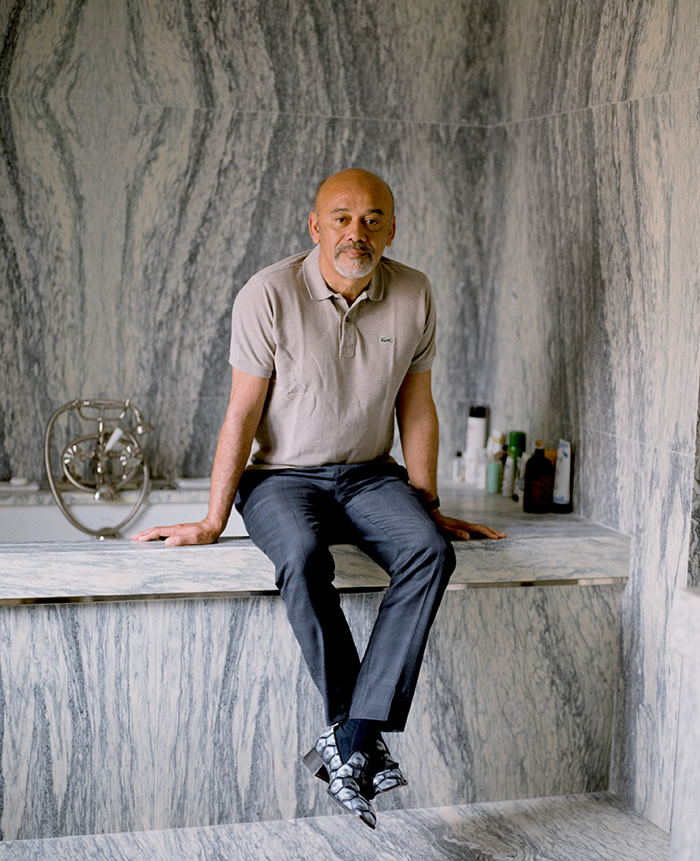

Another room that Louboutin loves is his bathroom, where he enjoys a steaming hammam each morning. He leads me through his bedroom — across a tiger skin rug and past rows of men’s shoes. There were 340 pairs at last count — mainly his own brand but also by Nike and Dries Van Noten. Louboutin’s butler Safqat points out that this last count was in 2017 so the total now may be higher.

The bathroom is grey Italian marble juxtaposed with églomisé glass panels from India. “I wanted to have a bathroom mixed between an Indian Maharaja’s 1920s bathroom and something quite traditional that you would find in Claridge’s,” says Louboutin. “This marble makes me starving because it looks almost like Roquefort.”

It’s easy to get lost in the corridors of Louboutin’s imagination but back in the sitting room the conversation turns to business. The group has expanded beyond women’s shoes into men’s footwear as well as handbags, fragrances and make-up. Christian Louboutin is a privately held company and so doesn’t disclose its financial performance but it says it is profitable, and it produces more than 800,000 pairs of shoes a year.

I ask the designer whether Christian Louboutin will remain independent. Over the years he has declined many offers for the business, including from Bernard Arnault’s LVMH, the world’s largest luxury group by revenues. “You can never say forever but it’s been 27 years and for me it’s an important thing to be free,” he says. “It goes into my design and if you’re not a free person it’s difficult to keep on at the same pace. It’s actually a condition for my sanity and the sanity and the quality of my work.”

Favourite thing

A long transparent box gently tips from side to side. Inside, a blue liquid froths, making waves like the ocean. “It’s a very important piece for me because it reminds me of my childhood,” says Louboutin.

It was once in the window of a shop selling lava lamps in Paris and it used to mesmerise Louboutin when he walked past it as a young boy. Years later he chanced upon its new owner, a dealer in the Paris flea markets.

It was years before the dealer would sell it but the night Louboutin installed it he stayed up, transfixed by the tilting flume until the early hours. “You only regret what you didn’t buy,” he says.

Harriet Agnew is an FT correspondent in Paris

Follow @FTProperty on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments