Lucy Kellaway: We will miss the office if it dies

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

On my last day at the Financial Times in July 2017, the doorman who had greeted me every morning for the previous two decades enfolded me in a substantial embrace.

Take care Luce, he said.

I had been dry-eyed during the farewell speeches but this undid me. I pushed through the revolving doors for the last time, stood on the street outside and wept. What hurt so unexpectedly was not leaving a profession and a set of colleagues. It was leaving a physical place of work with its familiar habits and familiar doorman — it was leaving an office.

Offices, it seems, are now in mortal danger, rendered too expensive and too dangerous by Covid-19. For a quarter of a century, people have been confidently and wrongly predicting their demise — I remember Terence Conran telling me in the early 1990s that soon people would stop working in offices — but this time it may well be for real. If so, office workers everywhere should stand in the street and weep at what they are losing.

For 36 years I worked in an office, and for the last 25 I wrote about them. The office was a mainstay of my life. It not only provided me with a place of work and material for articles, but gave me routine, structure, amusement, purpose, many friends and a refuge in times of trouble. It was where I went to pass my days. The office was my rock.

I am well aware of the charges levelled at the office but am swayed by none of them. Offices are said to be inefficient, expensive temples to corporate vanity (which fell out of favour in 2008) and Petri dishes for pointless tasks. Workers commute to offices to use technology that they could use at home. The places are overcrowded, full of distractions, encourage presenteeism and, worst of all, infantilise workers with their bean bags and football tables.

The water-cooler century

At first offices resembled factories; later they became a second home. The FT’s chief features writer Henry Mance charts their rise and fall

I used to be slightly sympathetic to the argument that in an office it is easy to waste a whole day in dull meetings. But now I don’t even accept this: the thought of sitting around a real table with real people — and some decent biscuits — discussing solvency ratios (or anything at all) seems pretty attractive from where I sit now.

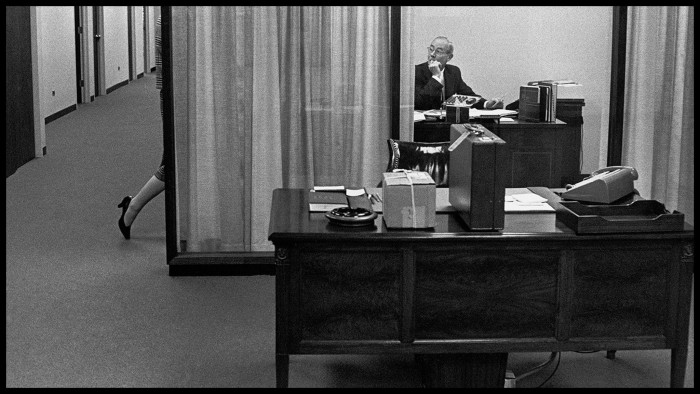

My love for offices may be partly because I was introduced to them in the 1980s, at the end of the golden age — pre-technology, pre-uniformity, pre-health and safety. It was a time of cast-iron typewriters, smoking at your desk, heavy drinking at lunchtime, canteens selling spotted dick, tea ladies and cake trolleys.

But what I really remember are characters such as the high-functioning alcoholic in the dealing room at JPMorgan who started each day by taking a nip out of his hip flask and then applying a coat of liquid shoe-shine to his already shiny brown shoes. There was the accomplished journalist at the Investors Chronicle who dressed like a tramp and would kip down for the night under his desk. Offices were full of shouting, brawling and bottom-pinching. It was sometimes nasty, mostly funny and never dull.

Modern offices, by contrast, are usually dull: quiet, boozeless and impersonal with their ergonomic chairs, glass-walled meeting rooms and half the people working from home. But, even so, we need the office as much as ever.

The most important thing — which should make the office less an employer’s white elephant than its biggest bargain — is that it gives work its meaning. Most of what passes for work in offices is pretty meaningless, and the best way to kid yourself it matters is to do it alongside other people intent on doing the same.

Even in interesting jobs like journalism, meaning comes largely from physical proximity to your colleagues. After six weeks of writing in her own bedroom, one friend reports: “I’m churning out the same old articles as before, only now I no longer give a crap”.

Without an office, without a body of people beavering away at the same place and time, it is hard to know how a company could ever create any sort of culture or any fellow feeling — let alone anything resembling loyalty.

The office helps keep us sane. First, it imposes routine, without which most of us fall to pieces. The uptight schedule of most offices forces even the least organised person to establish habits. Even better, it creates a barrier between work and home. On arrival we escape the chaos (or monotony) of our hearths; better still, we escape from our usual selves.

One of the beauties of the office is its artificiality — it demands a different way of behaving, a different wardrobe and even a different language. Having two selves with two different outfits and two ways of being is infinitely preferable to having just one: when you get tired of your work self, return to your home self.

Offices are also the funniest places in the world. The flipside of the idiocy of management is the hilarity and cynicism of workers. I remember the merriment when a past CEO sent us an over-the-top motivational New Year memo saying, “what fires me up is knowing that each of you comes to work every day ready to do something miraculous”. Gleefully, we sat around and tore this to shreds. A miracle per person, per day? Even Jesus Christ couldn’t manage that.

When cynicism failed, there were always pranks. I remember being called one morning by an incandescent CEO about a critical article I’d just written on his company. I prevaricated, oblivious to the fact that the caller was not the CEO but a colleague ringing from the other side of our office — much to the amusement of everyone else. In time, I forgave him. In fact, I came to see it as so funny that I married him.

This was yet another function of the office: it was highly likely to furnish you with a spouse. People who had failed to find partners at university or through friends generally picked one up at work. It was all so easy: you would go out for a drink at the end of the day and then one thing would lead to another. The fact that the decline of the office and the rise of online dating have gone hand-in-hand isn’t particularly surprising.

Short of marriage, offices from the beginning of time have been great places for lust. As Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary on June 30 1662: “Up betimes, and to my office, where I found Griffen’s girl making it clean, but, God forgive me! what a mind I had to her, but did not meddle with her.” In 21st-century offices, where meddling is not only discouraged but illegal, invisible lusting is probably as big as ever. It gives interest to an otherwise dull day.

In addition to providing real husbands, offices provide work husbands too. I had seven of these in the course of almost four decades and can confirm that the office spouse is one of the best relationships ever invented. They are the default option for a sandwich at lunch, someone who supports you in all matters, someone to gossip with. It’s like a real husband, only better because you don’t fight over whose turn it is to unload the dishwasher. There was a study done proving that people with office spouses were happier, more loyal and worked harder. Which is no surprise to anyone who’s ever had one.

A final benefit of the office occurred to me in the past six weeks: it is a great leveller. Yes, the boss tends to get the best view, but everyone is in the same office building with the same common spaces. Contrast that to the inequality working from home exposed in every Zoom conference: some people work from oak-beamed barns in the Home Counties, others from cramped cupboards.

There is one bad thing about the office that even most office-philes will admit: the commute is generally a downer. But now that I no longer go anywhere at all, I don’t remember why everyone made such a fuss about this. I spoke recently to one of my dearest friends from FT days who sounded in low spirits. I’m really missing the Northern line, he said.

In my old life I was always irritated by the homily “No one ever said on their death bed: I wish I’d spent more time in the office.” I now understand why that jarred so badly. To wish for more office time is an entirely reasonable thing to say with your dying breath. I spent 35 rich and happy years in offices. I fear that my children won’t get that chance.

Lucy Kellaway is a co-founder of Now Teach and a former FT management columnist

Main image is Lucy Kellaway at her FT desk in 2009, courtesy Bill Knight

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen to our podcast, Culture Call, where FT editors and special guests discuss life and art in the time of coronavirus. Subscribe on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you listen.

Letters in response to this column:

Workplaces are part of our culture and economy / From Nick Riesel, Managing director FreeOfficeFinder.com, London EC1, UK

Evoking the office, and the itch for a weekend read / From Simon Larter-Evans, Northend, Oxfordshire, UK

Comments