Asia takes lead in rush to monetise innovations

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Patenting has never been more popular. Applications have reached record levels at the world’s main patent offices — fuelled by a sustained increase in applications from Asia. Patent filings by Chinese companies outside their home country have risen 30-fold so far this century.

The boom is an encouraging sign for future economic growth, as companies intensify their efforts to turn the results of research into innovative products and services.

The European Patent Office (EPO) received 160,000 applications last year, up 4.8 per cent on 2014. The World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO) reported a 1.7 per cent increase to 218,000 in filings under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) which provides some international harmonisation. These numbers conceal a strong tilt towards Asia, which has more than doubled its share of PCT applications since 2005 and accounted for 43 per cent of last year’s global total.

Within Asia, the big story is China, which has experienced much the fastest growth in patenting of any large country since the start of this century. Although this does not come as a surprise, given the speed of Chinese industrial development, the figures are still remarkable.

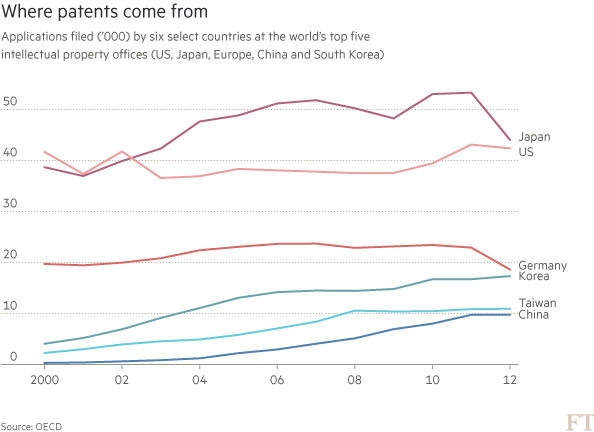

Statisticians at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development have analysed for the FT the geographical distribution of patents filed in the world’s five most important IP offices (Europe, US, Japan, China and South Korea) — so-called IP5 patents. In 2000, just 331 IP5 applicants were based in China; this had risen to 9,767 in 2012.

“While the Chinese growth rate in patenting since 2000 does stand out, it started far behind its competitors,” says Mariagrazia Squicciarini, OECD patent specialist. Mainland China had not caught up with Taiwan by 2012

and the Asian powerhouses of Japan and Korea are still well ahead in absolute numbers. “Japan has always had a positive attitude towards IP rights embedded in its business culture,” she adds. China does not have such a tradition but “there is an active policy by the Chinese government to foster patenting”.

Although more recent data are available from WIPO, EPO and other offices, Ms Squicciarini says their conclusions about applicants’ country of origin must be treated with caution, because names on IP documents are not a reliable guide to ownership. Further investigation is also needed on the industrial sector in which the applicant wishes to apply the patent.

“There is a shortage of good data about patenting, which has hindered analysis of innovation policies,” she says. The OECD team has attempted to nail down ownership by scrutinising patent office data with the Orbis global database of 200m private companies worldwide.

A striking feature of Chinese patenting is that it is distributed much less evenly across different fields of activity than that of other big countries. More than 85 per cent of China’s IP5 patents are in telecommunications, computing, digital communications and audiovisual technology. In areas such as chemicals, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology China is hardly represented.

Most Chinese patents do not reach the international arena — and are therefore not counted in the OECD or EPO data. The vast majority are filed only domestically: WIPO’s World Intellectual Property Indicators report in December showed that China’s State Intellectual Property Office (SIPO) received a staggering 928,000 patent applications in 2014. It was followed by the US (579,000), Japan (326,000), Korea (210,000) and the European Patent Office (153,000). The WIPO figures indicate that Chinese inventors filed only 36,700 applications outside China in 2014 — far behind the number from the US (224,000), Japan (200,000) and Germany (106,000).

Many foreign companies are reluctant to patent in China, explains Mark Schankerman, intellectual property expert at the London School of Economics, “because it has been almost impossible to enforce patent claims through the Chinese courts”.

Prof Schankerman compares China’s attitude today with that of the US in the early 19th century. “Americans were then ripping off IP from the UK because they were consumers rather producers of technology,” he says. “Now the US is in the vanguard of producers and the Chinese are like the old Americans.”

The Chinese market is so big that international companies cannot afford to ignore it and increasing numbers are protecting IP in China.

Prof Schankerman predicts that Beijing will soon encourage this trend by increasing enforcement. “One reason is that it wants to encourage foreign investment, which will not come if IP is systematically stolen,” he says. “The other reason is that China is moving from being a low-wage consumer to become a producer of technology.”

Analysis of different fields demonstrates an increase of IP5 patenting in most physics-based sectors such as computer technology and digital communication. Patents based on chemistry and biology are in decline, including pharmaceuticals and biotechnology.

These differences stem partly from faster technical advances and market growth in information and communications technology (ICT) than in the life sciences — and partly because of structural differences between them.

“ICT products are becoming ever more complex,” says Ms Squicciarini. “To get a smartphone on the market you may need hundreds of patents. And think about the digitisation of the economy — think of all the electronics going into cars, for example.”

“In ‘non-complex’ technologies such as pharmaceuticals very few patents are needed on a product,” adds Prof Schankerman. “For a drug one patent may be enough. In contrast, complex IT products are surrounded by ‘patent thickets’. Companies obtain patents to use as bargaining chips and give them freedom to operate in a field such as smartphones or computers.”

Not surprisingly, the companies most active in the patenting arena are all in electronics and IT — and the top seven are based in Asia, according to the OECD’s analysis of corporate patents between 2010 and 2012. General Electric of the US comes in at number eight, while the highest placed European company is Robert Bosch at 12. All are well-known household names with the exception of Taiwan’s Hon Hai Precision Industry, the global electronics industry’s largest contract manufacturer, which filed 3 per cent of IP5 patents.

Comments