So you think you know your supply chain?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

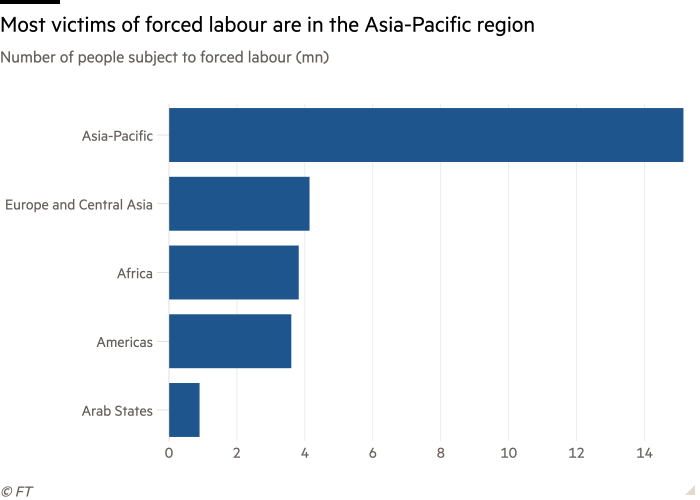

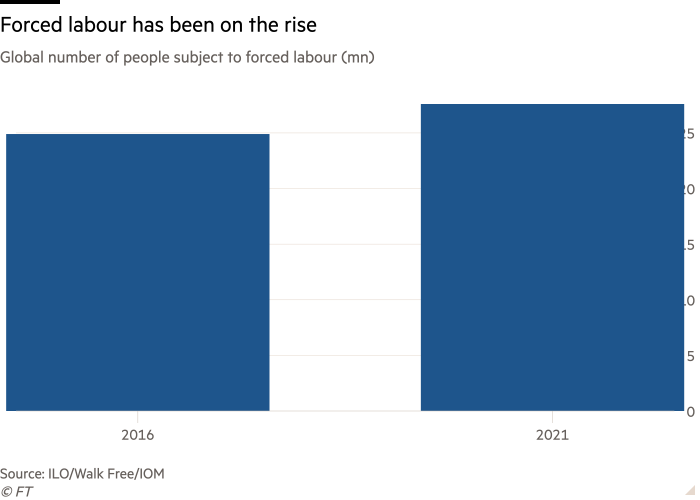

In 2018 the Responsible Sourcing Network presented an alarming figure: twice as many people worldwide were in forced labour as had been taken to the Americas during the 300 years of the transatlantic slave trade.

In the five years since that statement by RSN, a US non-profit organisation that combats human rights and labour abuses in raw materials sourcing, the upending of supply chains caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has put millions more workers at risk of this kind of abuse.

Statistics on forced labour and human rights violations make for grim reading, not least because efforts to end such abuse have been going on for decades.

Bennett Freeman, a corporate responsibility adviser and vice-chair of RSN, remembers the birth of organisations such as the Clean Clothes Campaign in the Netherlands (1989), the Ethical Trading Initiative in the UK (1998) and the Fair Labor Association in the US (1999).

“This agenda emerged in the early to mid-90s and the moving parts were visible and working by the end of the 90s,” says Freeman, a US state department human rights and labour official at the time. “We’re talking about a quarter of a century of focus, effort, initiatives, successes and failures, and frankly there’s a big question to be asked about how much progress we’ve made.”

He is not alone in wondering. Alison Taylor, a specialist in ethical business at the Stern School of Business, New York University, likens the situation to a game of Whac-a-Mole. “There will be a revelation of some horrible abuse and collective action from the companies in question,” she says. “Some of that will be quite effective but then another problem will pop up somewhere else. It’s all very reactive.”

But with continuing scrutiny from consumers, activists and the media — and growing interest from investors — companies are now under more pressure than ever to meet obligations over responsible sourcing.

When we asked FT Moral Money readers to point to the biggest risks posed by unethical labour practices in supply chains, most picked reputational damage while others cited consumer boycotts and legal challenges.

No silver-bullet solution has appeared since human and labour rights abuse emerged as a corporate risk in the 1990s. Thirty years on, companies are still not prioritising action in this area. Asked how important ethical supply chain practices are to their organisation, most readers of FT Moral Money ranked them the same as other sustainability challenges.

Nevertheless, in sectors such as apparel and footwear, which have faced particular scrutiny, the years of effort have begun to pay off. At the same time, innovators have developed technologies that can track products back to individual factories, fisheries and plantations.

Alongside emerging legislation that imposes financial penalties for non-compliance, this has led to cautious optimism about the emergence of a new era — one in which fewer iPhones and sneakers are made by children or exploited workers.

Not an out-there problem

At the heart of the challenge is the length and complexity of the journeys that products take as raw materials become finished goods. Many pass through the hands of thousands of workers in enterprises that range from huge factories to agricultural co-operatives, micro businesses or farms of just a few hectares.

Even the sourcing of raw materials — where Patricia Jurewicz, chief executive of RSN, sees some of the worst abuses — is fraught with complexity. “There is a huge web of so many different actors, of transportation of materials, of the different processing and blending,” she says. “It is really hard to peel all that back.”

Disruptions such as the pandemic, inflation and currency fluctuation exacerbate the problems that face workers, as do geopolitical upheavals. LRQA, a global assurance firm, formerly part of Lloyd’s Register, recently reviewed its 2022 audits — nearly 20,000 of them. It concluded that violence and macroeconomic volatility increased the risk of child labour in 18 production markets.

Purchasers’ buying practices can also create problems. In 2017 and 2018, Mark Anner, a professor and an expert in pricing practices at Pennsylvania State University, studied 340 Indian factories making clothing for export. He found that price pressures and shortened lead times led most suppliers to raise production quotas for workers, maintain below-subsistence wages and make overtime obligatory.

Anner’s analysis also revealed a greater reliance on female and migrant workers, the imposition of short work contracts to avoid paying benefits, and outsourcing to unregistered factories. Workers who failed to meet production targets were verbally and even physically abused.

“It’s not just an out-there problem,” says Caroline Rees, president of Shift, a non-profit organisation that is a centre of expertise on the UN guiding principles on business and human rights. She argues that when buyers push down prices, particularly at a time of rising input costs, suppliers’ struggle to survive will always win out over codes of conduct.

“There’s been too much externalising the problem then coming in behind to say, ‘let’s be part of the solution,” she says. “[This never questions] how much internal practices or the business model itself is creating the context for that problem.”

As procurement decisions make their way through the supply chain, it is workers who suffer most. “Those at the top of the supply chain have incredible power and resources,” argues worker rights advocate Cathy Feingold, director of the international department at AFL-CIO, the US’s largest trade union federation. “They should be responsible for assisting suppliers in having a supply chain that upholds their commitments to good worker and human rights.”

Scrutiny finds a new home

As a student in 2001 Jonah Peretti, who went on to co-found the Huffington Post and BuzzFeed news outlets, took up an offer by Nike to personalise his trainers. He asked for the word “sweatshop” to be stitched into them — and his email exchanges with the company were broadcast globally. The age of online consumer activism had arrived.

What followed was a wave of interest from consumers in knowing that what they were buying was not made by children or underpaid workers in dangerous or sweatshop conditions.

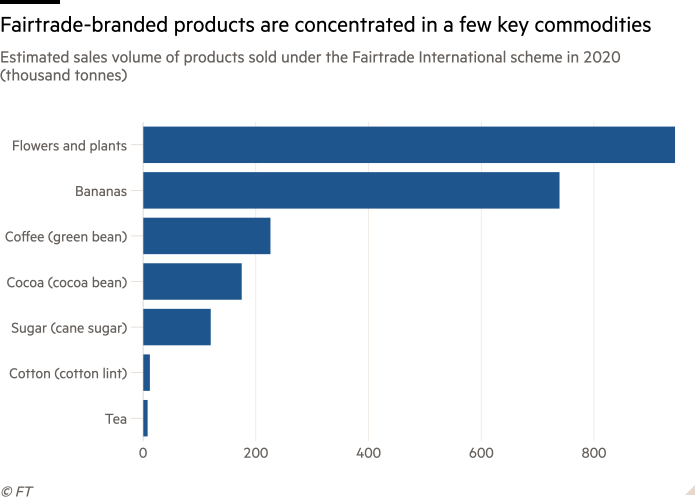

Shoppers began to vote with their wallets. Between 2004 and 2016, Statista estimates that retail sales of products certified by Fairtrade International rose by nearly 10 times, from €830mn to €7.9bn. At the same time, new digital tools emerged to help consumers make more ethical choices, including QR codes, mobile apps and interactive websites.

In the end, it may not be shoppers pushing companies hardest. The Statista research, published in 2021, found that only 26 per cent of US consumers would pay a premium for fairly traded food and drink.

“It’s hard to engage consumers,” says Rees. “I feel there’s a ceiling on the percentage of consumers for whom that will tip the balance.”

Consumer pressure can only go so far, says Shawn MacDonald, chief executive of Verité, a non-profit organisation that highlights and remedies supply chain violations. “It’s not fair to expect consumers to hold companies accountable.”

The investment community, meanwhile, is increasingly a force to be reckoned with. “I have [sustainability executives] frequently tell me that when investors call, that is when I can get the C-suite’s attention,” says MacDonald.

Yann Wyss, global head of social impact and human rights at Nestlé, knows how this works in practice. He has seen a sharp rise in interest from investors since joining the company 12 years ago. “Back then I would attend maybe a call a month with investors,” he says. “These days it’s more like a call every two days.”

The questions investors ask vary. According to FT Moral Money readers, they range from the origins of the materials that companies use to the nature of local labour practices.

Finding answers can be tough for investors. “Getting a baseline understanding of these issues is incredibly hard,” says Dan Hochman, head of sustainability research at Bridgewater Associates, the asset manager.

He compares data on supply chains with that now available for carbon emissions. “We’re so much earlier in the data evolution,” he says. “Almost by definition some of the worst parts of the supply chain happen in the shadows.”

For investors, this means looking beyond compliance or audit data, or whether companies have a supplier code of conduct or a human rights policy.

At Wellington Management, due diligence in its Global Stewards fund covers everything from whether a company is meeting its legal obligations to how it holds suppliers to account on issues such as fair wages and working conditions, as well as what it is doing on the ground and through third-party assurance firms to verify all this.

In 2021, for example, concern about the use of forced labour in China’s Xinjiang province prompted Wellington to seek an assurance that Inditex, which owns Zara, the fast-fashion retailer, did not source its cotton from the region — which it was able to confirm.

“You get them on the phone and you unravel how they work, how their supply chain is overseen and how they have confidence that they aren’t involved in that region,” says Yolanda Courtines, an equity portfolio manager at Wellington.

Needless to say, this is harder than verifying reductions in carbon emissions. “You can say we want to reach net zero and that’s a pretty common standard,” she says. “But how you roll up all the different issues around modern slavery — that is much more complex.”

Behind the story: NBIM and Unicef

UN agencies often work with global buyers to tackle problems such as child labour. In one such initiative, however, the partner was not a company but an investor.

In 2017, the Norwegian arm of Unicef, the UN agency for children, joined forces with Norges Bank Investment Management, which manages Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, to establish a children’s rights network.

The idea was to bring together companies in NBIM’s portfolio, which includes Adidas, H&M and VF Corporation, to develop a practical guide that could help shape business practices to protect children.

NBIM is no stranger to the issue. “Over the years we’ve addressed a number of child and human rights risks as part of our ownership work,” says Caroline Eriksen, its head of social initiatives.

“Companies can have an impact on children through their operations, supply chains and the use of their goods and services,” she says. “That can entail a risk to companies and to us as an investor, both from a financial perspective and a responsible business conduct perspective.”

The result was a guidance tool and a compendium of case studies. The benefit is being felt at Fung Group, the Hong Kong sourcing group, where staff use the company’s WorkerApp to find out about parenting, nutrition, health, finance and hygiene.

Meanwhile, the UK clothing brand Next set up a team to make sure that its policy on child labour would be implemented consistently, especially in places where local norms might differ from international standards.

Both Unicef and NBIM were keen to highlight practical approaches. “It was important for us that the guidance tool focused on what companies can do, and what are the best practices out there to inspire others,” says Eriksen. “It’s going beyond the policies to seeing what’s working.”

Regulators show their teeth

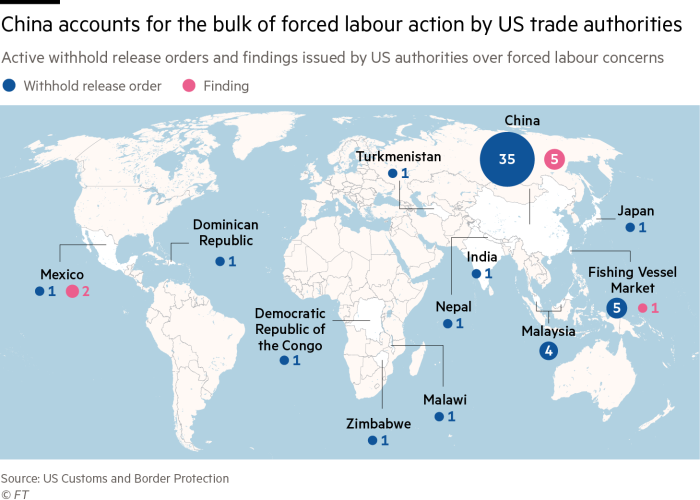

In March 2022 at the port of Baltimore, Maryland, customs officers seized four shipments from Malaysia with a combined value of almost $2.5mn. These were not narcotics, counterfeit products or goods from embargoed countries. They were palm oil products destined for a processing facility in Delaware.

The cargo was seized because of the alleged use of forced labour. Officials can use a withhold release order, or WRO, to detain goods until they are re-exported or until the importer can show that no forced labour was used in their production. If neither happens, the goods can be destroyed.

It is not the only ban importers now need to worry about. Since June, the US has used the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act to prohibit imports from the Xinjiang region of China, where there have been allegations of human rights violations that include forced labour.

These are not regulators’ first efforts to combat forced labour. Issuance of WROs falls under a more than 90-year-old law: the Tariff Act of 1930.

In recent years forced labour has been targeted with laws including the California Transparency in Supply Chains Act of 2012 and the Modern Slavery Act 2015 in the UK. Some critics say this legislation lacks teeth, however.

The Californian law only requires companies to report publicly on efforts to eradicate human trafficking and slavery, even if this is insufficient; it does not mandate new measures. Similarly the emphasis of the UK’s law is on reporting. Its lack of financial penalties in 2021 for non-compliance prompted a parliamentary committee to call for tougher enforcement.

“These were well-intentioned but fairly limited, given the lack of back-up beyond what was expected to be disclosed,” says Eric Biel, senior adviser at the Fair Labor Association in the US.

He says the nature of legislation now emerging is markedly different. “With the Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act and the use of WROs, it is no longer a choice,” he says. “That is where government engagement has been a game-changer.”

Rees, of Shift, agrees that WROs are an effective tool for change. “It is mission-critical — companies cannot get their goods into the country.”

At one time, the main risk to a company found to be using forced or child labour was to its reputation. “Now it’s costing millions of dollars. The financial hit is real,” says MacDonald of Verité.

Import bans are not the only sticks regulators can wield. The EU is working on a directive to require large businesses to disclose and manage environmental and human rights standards along their supply chains. Germany has such a law in place already.

Debates are taking place on whether the best way forward is an import ban, which the EU is also considering, or due diligence. “For the EU legislation, so much is going to depend on the enforcement and enforceability,” says Rees.

She warns against legislation that permits a tick-box approach, or one in which companies pass responsibility for compliance back to suppliers that are not equipped or cannot afford to handle it.

The discussion will continue, alongside calls from those who would like to see rules made consistent internationally.

Most agree, however, that regulations on forced labour have entered a new era, one in which companies failing to provide assurances that their goods have been responsibly sourced will be deemed negligent.

In other words, ignorance is no longer bliss.

Digital detective work

If regulators are pressing companies to disclose their products’ provenance and how they were made, tracking and tracing technologies — from satellite imaging to the isotopic fingerprints on foods and textiles — are making it harder to claim ignorance.

At Verité, MacDonald has watched with interest as science has enabled the work needed to find out whether goods are made by children or bonded workers. “I’ve been doing this work for a long time,” he says. “Five years ago I never would have thought of something like isotope tracing.”

Through a project called Streams (supply chain tracing and engagement methodologies), Verité is working with the RSN and others to identify the most effective approaches and which to apply more broadly.

Technology is even shining a light on one of the murkiest supply chains: that for seafood. Evidence has emerged of workers being forcibly held on unregistered “ghost ships” on the seas around south-east Asia and other regions. Many are forced to work 20-hour shifts and have been beaten or killed.

Until now, such vessels have been hard to track since they often disable the automatic identification system (AIS), which provides location and other data to other ships and to coastal authorities.

However, Global Fishing Watch — a partnership between conservation organisation Oceana, digital mapping watchdog SkyTruth and Google — is using machine learning to flag up when boats’ location beacons are intentionally turned off, suggesting unregulated fishing activity.

GFW makes this data freely available on its platform. “We are working with port authorities to help them identify which vessels they should inspect,” says David Kroodsma, the director of research and innovation at the organisation.

Mission-driven investors take a keen interest in these kinds of technologies. Working Capital is among them. An early-stage venture fund, it was incubated at Humanity United, part of the Omidyar Group.

Its investments include OpenSC, which uses data science and machine learning to verify ethical production claims, and internet of things technologies to trace products across the supply chain. Another is Kenzen, whose wearable device for industrial workers can detect risks such as heat stress and fatigue that could lead to injuries.

Still, Ed Marcum, the fund’s managing director, believes that responsible sourcing technology has some way to go. “There’s demand for information,” he says. “The problem remains that the quality and scale is limited, especially when it comes to labour rights.”

One investment by Working Capital that is achieving scale is Altana AI, a New York-based start-up whose clients include US Customs and Border Protection, BMW, Merck and Maersk. Altana has an ambitious goal: to build what Evan Smith, its chief executive and co-founder, calls “Google Maps for the supply chain”.

As well as using public data, Altana applies machine learning to non-public data, such as shipment bookings, purchase orders and bills of materials, to build a picture of what is happening across supply chain networks. This allows customers to identify risks such as worker exploitation, whether in regions, manufacturing facilities or raw materials.

“We’re connecting the dots across product flows, physical shipment locations, value-added manufacturing and then end-use and distribution,” says Smith. “We take the thumbprint of the data, which benefits the entire network, but sensitive data elements and raw data stay private.”

Smith believes this approach underpins something he sees as essential in managing supply chains: a change in mindset that treats them not as outsourced buyer-supplier relationships but as multi-tiered networks. “That’s the key,” he says.

All together now . . .

Advocates for responsible sourcing practices are the first to point out that while data is a critical tool, it cannot tackle labour abuses alone. “You can have the fanciest technology but in the end we need to make sure workers feel their companies respect their right to a collective voice,” says Feingold of the AFL-CIO. “They’re the ones who can tell you what is happening in their workplaces.”

When she was leading Unilever’s social impact work, responsible and sustainable business expert Marcela Manubens learnt the importance of including suppliers and their employees in decision making processes. “When you think about the progress made, in many instances it is because we listened to workers, to management and to communities,” she says.

In 2007, to equip female workers to play a bigger role in decision making — both at work and in their communities — Gap, the clothing company, launched Pace, a voluntary programme that delivered life skills and technical training to women in the factories that made its garments.

Yet when other brands began similar initiatives, this created a problem: multiple sessions were being delivered in the same facility. “Workers would be going through similar training, depending on which buyers were sourcing from that factory,” says Daniel Fibiger, head of responsible sourcing at Gap.

To fix this, four organisations — Better Work, an International Labour Organization initiative, Gap’s Pace programme, humanitarian agency Care and advisory BSR’s HERproject — came together to launch Reimagining Industry to Support Equality, or Rise, to give workplace training to increase women’s wellbeing and skills.

The group works with 50 of the world’s largest apparel brands. “The integration does away with duplication. It brings this proven training to other factories that might not otherwise have been able to benefit,” says Fibiger.

As the Rise initiative suggests, if companies have learnt one thing over decades of working on responsible sourcing it is that they cannot make progress on their own.

Sometimes, this means building local capacity, as Walmart has done in Thailand. “They had laws against forced labour but there was an opportunity to enhance enforcement,” says Kathleen McLaughlin, Walmart’s head of sustainability.

Part of the challenge, she says, is that law enforcement officials sometimes lack the capacity to build cases against traffickers. In Thailand, this led the company to make a grant through its foundation to the International Justice Mission, a US-based non-governmental organisation. This enabled the IJM to open an office in Bangkok and to train police officers in how to build strong cases that have the best chance of securing convictions.

Building capacity can also involve bricks and mortar. In Ivory Coast, for example, the sustainability goals of Nestlé’s income accelerator programme — which gives farmers direct payment incentives — include increased school enrolment to help prevent child labour. But in communities that have no schools, the company has sometimes needed to build them.

“You could argue it’s not our job to build schools,” says Wyss. “But sometimes the government has limited resources and other priorities. It’s a combination of us stepping in but also engaging in discussions and making them aware of these gaps.”

The Cotton Campaign is an example of what can be achieved by bringing together organisations from all sectors. In March 2022 the campaign, which sought to stop the systematic use of forced labour by the government of Uzbekistan, was able to announce the end of its 12-year boycott of Uzbek cotton.

The victory came as a result of years of efforts by Uzbek activists, international advocates, multinational companies, human rights organisations and others.

“From the beginning, this was a multi-stakeholder coalition that brought together not just the usual suspects but also big apparel brands and their trade associations,” says Freeman, who co-founded the campaign. “That was the secret sauce.”

Case study: The Responsible Contracting Project

Sometimes responsible sourcing solutions lie close to home: including in contracting practices and the way procurement teams draw up legal agreements with suppliers.

Until recently, says Sarah Dadush, a professor at Rutgers Law School, New Jersey, the focus of contracts has been to manage only the buyer’s risks — risks related to delivery delays, product defects and so on.

“Contracts are part of a smart mix of interventions but they’re really important. Until now they haven’t been designed in a way that supports human rights,” says Dadush, the project’s founding director.

The Responsible Contracting Project, of which Dadush is a director, plans to change this. Originally an initiative of the American Bar Association, the project is developing a model contract that sets out new obligations.

In it, buyers and suppliers must each conduct human rights due diligence before and during the term of the contract. Both parties must also adhere to responsible sourcing and purchasing practices.

The model contract also sets out processes through which buyers must provide proportional remediation in cases where purchasing practices, such as last-minute changes or short lead times, lead to problems such as human or labour rights violations.

“Contracts are the legal links of the supply chain,” says Dadush. “So if you want to change the supply chain, one of the places to look is the contract.”

A possible turning point

Battles to end worker exploitation or prevent child labour are far from over. In fact, geopolitical and economic upheavals, as well as the pandemic’s long tail, have exacerbated these problems in many places.

Among the more worrying statistics, for example, is a 2022 ILO estimate that more than 27mn people worldwide — equivalent to the population of Shanghai — are working in situations of forced labour.

Yet in some places, years of work on the ground with governments and NGOs appear to be paying off. “One must look at the data at a national level and preferably even at the factory level,” says Fibiger. “I’ve visited some of the same factories I visited 10 years ago and today they are completely different places to work.”

New sources of pressure may help. While activists have long understood how to express disapproval of poor labour practices, investors are also making their voices heard. In 2021, for example, investors representing more than $6.3tn in assets sent a statement to the European Commission and the European parliament in support of mandated human rights and environmental due diligence.

Feingold cites the commitment she has seen from Norway’s sovereign wealth fund to using its financial clout to drive better labour standards. “That could be huge if they take action,” she says. “That’s where I get excited.”

In 2021, Just Capital, which monitors the effect of business on society, found that companies that explicitly mention human rights in their supplier code of conduct tended to outperform those whose code omits them.

For Jurewicz of the Cotton Campaign all this is a cause for optimism. “A lot of people ignored this for a long time,” she says. “But something is finally happening.”

What comes next may be a case of two steps forward, one step back. But the current combination of forces — collaborative, regulatory, financial, technological and legal — may just be enough to start laying the foundations for global supply chains that benefit, rather than abuse or exploit, the people who work in them.

Comments