1932, Picasso’s year of wonders

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In January in “The Dream”, her curvilinear forms swell to fill the armchair where she dozes in sexual reverie, upturned face resembling an erect penis. In March, against a diaphanous blue curtain, she is a lilac arabesque, stretched out in sleep, sprouting a philodendron plant and surveyed from above by an impastoed sculpture of her own profile: the spring nymph of “Nude, Green Leaves and Bust”.

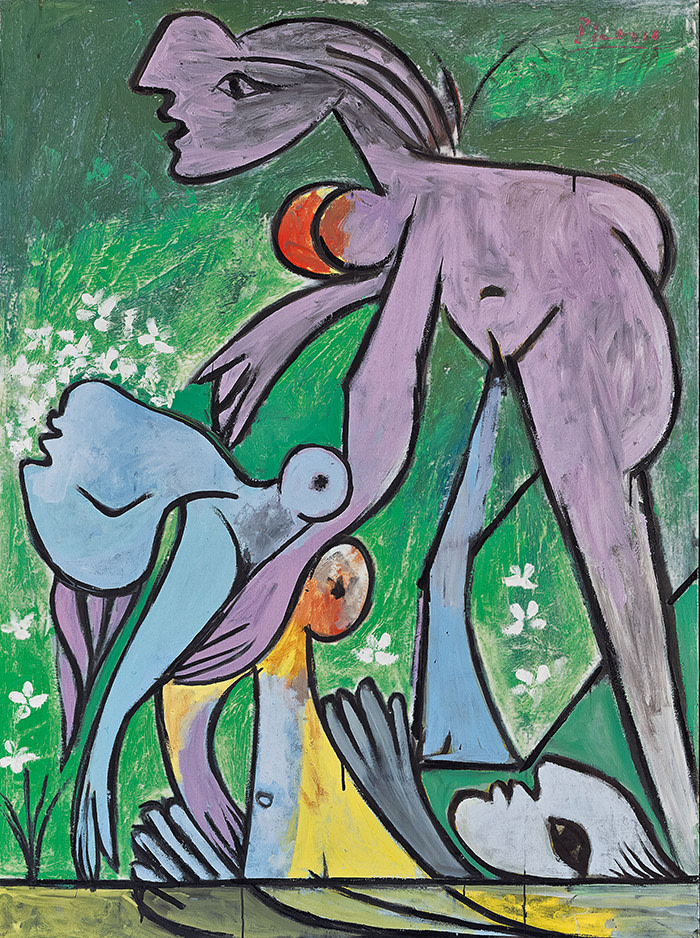

Summer approaches, and she dissolves into the inviting, explicit geometric patterns of “Woman on the Beach”, which a pre-eminent Paris dealer rejected because “I refuse to have any arseholes in my gallery”. By December, as a skeletal bather, eyes closed, head thrown back, breasts thrust up, about to drown before being hoisted into the arms of her lavender alter ego, she is victim and saviour alike in “The Rescue”, a frieze of turbulent figures in flattened tones — formally heralding “Guernica” — where pleasure and violence, sex and death, entwine.

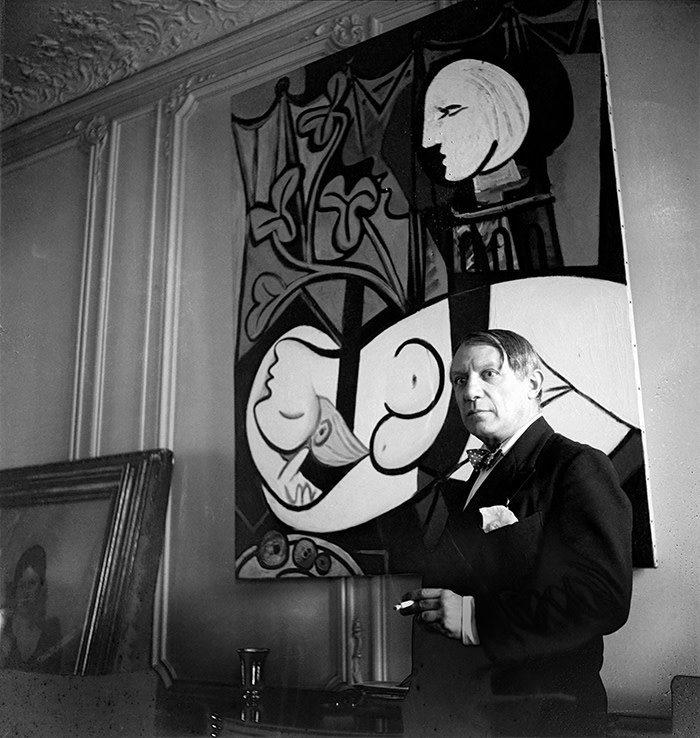

Picasso 1932: Love, Fame, Tragedy, Tate Modern’s stellar record of the artist’s transformations and deformations of his lover Marie-Thérèse Walter over a single annus mirabilis, is a pastoral drama of magnificent, monumental showpiece paintings powered by intense private feeling. The show follows work-by-work every creative and biographical twist, as Picasso, 50, works with maniacal ambition towards his first retrospective, responding to winter trysts in secret interiors, seaside Arcadias, an autumn when Marie-Thérèse became ill (and bald) from an infection caught swimming in the Marne.

“Executed between three and six o’clock on January 23, 1932”, Picasso scrawled triumphantly on the stretcher of “Sleep”: Marie-Thérèse as serene mauve nude, arm rising in circular swoop to her head, blonde chignon flopping. Malice lurks behind the lyricism. Next to this homage to uncomplicated beauty hangs the ironic “Rest”, dated January 22: Picasso’s hysterical wife Olga as a livid pink snaking coil, black hair stiff as a comb, hands over head — ballet’s fifth position, mocking her dancer past — in a posture cruelly identical to that of Marie-Thérèse’s true repose in “Sleep”.

If Marie-Thérèse was the bright dream of youth against the daily reality of Olga, she was also the blank form, the compliant model reduced to rhythms of sensuous curves through whom representation, endlessly, became invention. By 1927, when he accosted Marie-Thérèse, then 17, outside Galeries Lafayette, Picasso’s postwar return-to-order aesthetic had run dry: the loans here of earlier works such as “Olga in an Armchair”, his Ingresque, melancholically chaste wedding portrait of his wife, contrast starkly with the playfulness inspired by his muscular young muse.

In “The Yellow Belt”, Picasso the clown gives Marie-Thérèse an erect, protuberant nose and melon breasts: a modern cartoon. In “Reading”, a book stands in for the triangle dip of her genitals, its fuzzy print implying pubic hair. Two versions of “Reclining Nude”, where she metamorphoses into a sea creature with flippers and tentacles, are brilliantly displayed alongside Jean Painlevé’s quasi-surrealist film “The Octopus”.

Smaller informal works, among the show’s revelations, feel fresh with the frenzy of their making: the trio “Nude before a Mirror”, “Reclining Nude” — the rough surface is a cardboard lid — and “Nude in front of a Mirror”, for example, paint fluid and restless, brushstrokes rapidly applied wet in wet, vitality and expressivity distilled in classical purity of line, were all completed in Picasso’s Norman hideaway Boisgeloup on June 26. Nearby, exuberant distorted busts of Marie-Thérèse’s Grecian profile star in a radiant, immersive installation evoking Boisgeloup’s sculpture studio.

Tactility of paint and plaster excites throughout; even objects seem alert to Marie-Thérèse’s touch. In “Nude Woman in a Red Armchair”, the chair’s scrolling arms mimic the figure’s sinuosity, straight wood, brass studs and hard leather upholstery offset soft, pliable flesh, and Marie-Thérèse’s accommodating moon face shines out like a light from the grey background.

Can the #MeToo era cope with these virtuoso stagings of submission and availability? Accessible Marie-Thérèses are in fact this decade’s market favourites of all Picasso’s works: “Nude, Green Leaves and Bust” fetched $106.5m in 2010, “The Dream” $155m in 2013. Perhaps Picasso’s biographer John Richardson is right that some Marie-Thérèses “flew off the easel rather too easily”.

Tate smartly counters their decorative multicoloured surface splendour with the black-and-white depths of the “Crucifixion” etchings, created in October in response to Grunewald’s brutal Isenheim altarpiece. These lend resonance to the ambivalence, extremism, notes of horror, which make the greatest Marie-Thérèse paintings fraught expressions of the complexity of power and desire — and compelling and topical now.

Tate’s highest of many high points is the reuniting, for the first time since their creation, of six majestic paintings dated March 2-14, culminating in the creamy rhapsody of splitting and unity “The Mirror” — head enfolded in arms, hips prominent, Marie-Thérèse turns to reveal sumptuous buttocks in reflection — and MoMA’s rarely lent “Girl before a Mirror” where the innocent, pale young woman faces her darkened, older image in a glass. This series brings to an apogee Picasso’s competition with the authority of ancient myth enlivened by experimental juggling with form as he draws on Cubist fragmentation, Neoclassical gigantism, Surrealist dream games, ever-bolder eroticism, to give the entire Marie-Thérèse oeuvre immediacy as well as historical grandeur.

The March group enacts Pygmalion. Picasso opens with still lifes depicting Marie-Thérèse stone busts, one paired with a palette. Then he brings his sculpture to life in paint in “Nude, Green Leaves and Bust”. This and its successor, the rapturous/stupefied figure in claustrophobic interior with plant “Nude in a Black Armchair”, where Marie-Thérèse’s hand morphs into a lily, challenge Matisse’s odalisques in sensuality and ornamental setting.

“When I paint a woman in an armchair, it’s old age and death,” Picasso said. This nude, tilted forward from the chair, is pressed so close to the picture plane that the immediacy becomes excessive, artificial; the Matissean interior dissolves and, as TJ Clark writes in the excellent catalogue, “the nude in her infinite distance and otherness confronts US”. Misogyny is part of this picture; so is fear, impotence, alone-ness: the leaves suggest flaccid penises, the body floats free of space, beyond our reach.

For Picasso art was “a form of diary” but also “a form of magic designed as a mediator between this strange hostile world and us, a way of seizing power by giving form to our terrors as well as our desires”. Some 86 years on, the enchantment holds: this is Tate’s strongest show since Matisse’s Cut-Outs, and likely to be London’s top exhibition of 2018.

To September 9, tate.org.uk

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments