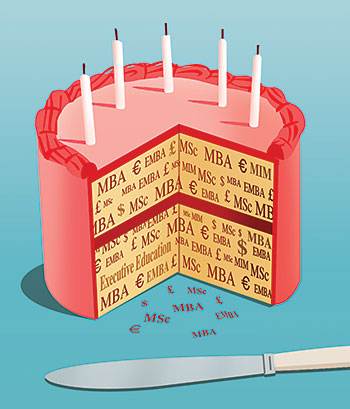

A look back at 20 years of business education in the FT

Simply sign up to the Business education myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

November was a special month for the business education team at the Financial Times, as we celebrated our 20th anniversary: 20 years of writing about business schools and their teachings in the “Pink ’Un” and, more recently, online and in magazines such as this.

So what has stood out in the European business education sector in that time — two decades that saw new schools arrive and, occasionally, established ones vanish?

In that auspicious first week in 1995 we reported on Insead’s fundraising campaign, the first significant one by a European business school and a bid to bankroll academic research to enable it to compete with its peers in the US.

Thus Insead set in train two of the most significant trends of the past 20 years: the quest to publish scrupulous academic research and the need to find non-governmental sources of funding. These days fundraising is a part of life for European deans and the top schools have proved particularly adept. Insead has also become a world leader in business research, coming ninth in that category in the FT’s 2015 Global MBA rankings. (London Business School, top of the European ranking, is sixth.)

The big news in the final two months of 1995 were the first moves by US business schools into the European market. First came the University of Chicago (Chicago Booth, as it is now called) with its plans to open a first campus outside the US in Barcelona and to run an executive MBA there. (It subsequently moved to London.)

At about the same time, Chicago’s neighbour Kellogg opted for a partnership model, signing up with German business school WHU, again to run an EMBA. The Fuqua school at Duke University, which made a play to attract European students through its global EMBA as early as 1995, also subsequently set up shop in Germany.

While Europe’s deans scratched their heads, their trade body, the European Foundation for Management Development, launched a counter-strike against its US equivalent, the AACSB (the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business), famous for its business school accreditation system. The result was Equis (European Quality Improvement System), the accreditation much coveted by European and Asian schools but largely still ignored in the US. This tale came full circle this year as the AACSB set up a European bridgehead in Amsterdam.

In 1999 we became news ourselves when we launched the FT’s first MBA ranking. London Business School was ranked eighth in the world, the first time a non-US school had been ranked so highly — or indeed ranked at all — in a major publication. The outrage on the Businessweek forums, the social media platform of the day, was visceral: how, posters raged, could any European school compete with those in the US? One comment became my particular favourite: “Della Bradshaw must be a cokehead.” Now, that’s what I call freedom of speech.

That same year came the Bologna Accord, which harmonised university systems across Europe. Germany’s Diplom-Kaufmann, the Netherlands’ doctorandus and Italy’s laurea all became masters degrees, spawning a new asset class, the masters in management, which has begun to compete with the MBA as the degree of choice for aspiring managers.

The first decade of this century saw a growing confidence at European schools as they looked overseas to develop relationships rather than competing with their peers at home. Campuses in the Middle East and Asia sprang up, the most significant being Insead’s in Singapore. Joint degrees, particularly with Chinese universities, flourished.

What is more, Asian students, and increasingly US students, decided they wanted to study in Europe. Fifteen years ago the majority of students at schools in Spain, France and Italy were locals; today in excess of 90 per cent of students are often international.

Overseas expansion helped offset the drop-off in students and funding at home, especially following the financial crisis of 2008 and the subsequent fracture in the eurozone. But business schools could not escape completely, and as public funding was slashed, mergers became almost commonplace, particularly in France and the UK, where Ashridge this year became the latest to join forces with another school, namely Hult of the US.

So what will the next 20 years bring? Will Europe see a second US invasion, as North American schools use online technology platforms to lure European students? Or will any European school break into the US market in a meaningful way? The next two decades promise to be as fascinating as the last two.

Comments