Global consultancies compete for share of Chinese market

Simply sign up to the Chinese business & finance myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Five years after reports that China had ordered state-owned enterprises to cut ties with US consulting companies, at least three of the Big Four consultancy groups, which all have significant US operations, are quietly claiming to do big business in the country. However, experts say Deloitte, EY, KPMG and PwC will have to navigate growing competitive pressures, the fallout from China’s trade war with the US and its slowing economy if they are to continue to attract business.

No one disputes that the opportunities are huge. Not only do China’s unwieldy state-owned enterprises (SOEs) need reform, but businesses need help adjusting to slower growth and the pain caused by the trade war with the US. On top of that, China has launched the Belt and Road Initiative, an ambitious vision for a network of infrastructure and trade that will encircle the globe.

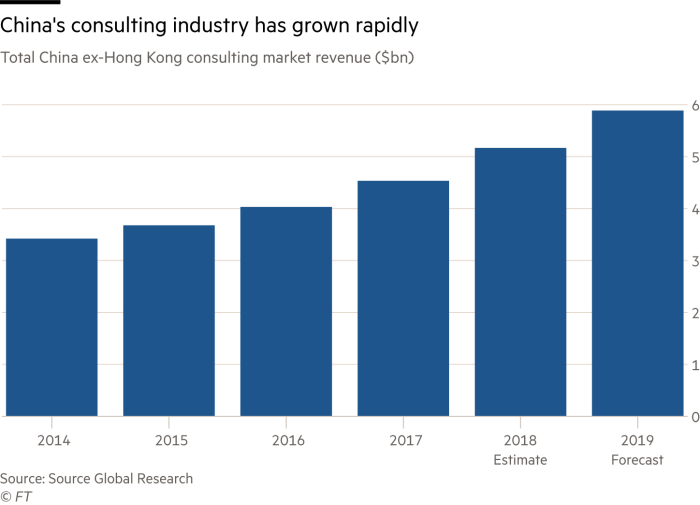

China last year grew at its slowest pace for 28 years, but at the same time the market for consulting in the country grew by more than 14 per cent to reach $5.2bn, according to estimates by Source Global Research. The analysts forecast the figure will rise to about $5.9bn by the end of 2019.

Foreign consultancies, while reluctant to give absolute figures, claim to be growing rapidly, in line with the broader market. Deloitte’s consulting business revenue in China grew 30 per cent, about twice the rate of growth achieved by its global consulting business, according to Stanley Dai, national consulting managing partner at Deloitte China. He is unconcerned by the slowing Chinese economy.

“It does not mean that there is no demand for consulting services during an economic downturn. When the economy is better, companies need advice on how to develop or grow, while advice on cost reduction and being efficient will be needed by the companies in the midst of downturn,” Mr Dai says. Deloitte’s business in China has not so far been impacted by the slowing economy, he adds, although it is hard to predict what will happen if growth slows further or if the trade dispute with the US is not resolved.

While international advisers are currently well-placed to expand in the country, there is no level playing field. Paul Gillis, professor of accounting at Peking University's Guanghua School of Management, notes that foreigners in the market will need to be watchful of “the rise of local consulting firms with growing expertise, lower prices and government support”.

China has been successful in nurturing a vibrant private sector and, despite their recent struggles for funding following China’s crackdown on shadow banking, private enterprises today still account for 60 per cent of China’s economic output. While the bloated SOEs continue to attract criticism for their inefficiencies, the private sector too can benefit from advisory services.

“Chinese companies need deal services — due diligence, merger integration and finance structuring. After being burned on early acquisitions where they tried to do it themselves, they now often use Big Four firms,” says Prof Gillis, a former partner at PwC.

He adds that, just as in other markets, multinational companies were keen to use big-name western consultancy firms as a kind of “career insurance” so that if anything went wrong with their business in China they could blame the consultancy and distance themselves from the failure.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative presents significant opportunities for all consulting firms, but particularly for the Big Four, which have extensive global networks. “Lots of Chinese companies will go overseas through the Belt and Road Initiative,” says Reynold Liu, head of management consulting for KPMG China. “Our global experience and global network will significantly help them, as we link our global experience with the local technology ecosystem.”

PwC saw such promising prospects that in 2017 it launched Belt & Road United, a platform that promotes sharing and exploring business opportunities associated with the project. The firm provides one-stop solutions to SOEs and large private enterprises looking to invest in businesses and explore partnerships with domestic businesses along the Silk Road economic belt.

“For example, we helped an SOE with plans to build power plants along the One Belt, One Road route. This included helping them to reach out to our member firms to offer specific local legal support and target vendor searches,” says Shirley Xie, PwC China and Hong Kong consulting leader, adding that PwC is seeing rising demand across its China businesses.

Ms Xie says helping companies adjust to changing technology is core to PwC’s business in China. This includes, in PwC’s case, supporting clients in the use of artificial intelligence, blockchain and the Internet of Things.

“Technology is becoming a big driver for demand for consulting services in China. Most of our consulting services will involve a technology aspect,” says KPMG’s Mr Liu.

Like Deloitte and PwC, KPMG claims to have enjoyed significant growth in China.

“Over the past four to five years when China GDP grew around 6-7 per cent annually, our consulting business [in the country] continued to grow at more than 20 per cent,” says Jeffrey Wong, head of advisory at KPMG China.

However, the world’s second-largest economy still contributes only 2-3 per cent of Deloitte’s global consulting revenue, says Mr Dai, and the Big Four face rising competition from local rivals as well as a possible drop in demand for their services from cash-strapped companies if the downturn in China’s growth story becomes more pronounced.

“Consulting always suffers in a slow economy because those services tend to be discretionary and companies defer spending their money,” says Prof Gillis. If that is true, and with no sign to the end of hostilities in the US-China trade war, which is already thought to be having an impact on some sectors of the Chinese economy, the Big Four might have to get used to slowing growth themselves.

Comments