Diversifying your portfolio in a changing world

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Every investor worth their salt knows that diversification is the key to giving your portfolio some protection against the inevitable ups and downs of markets. It’s a simple but important point about eggs and baskets.

However, no one worries about diversification when markets are going up. Only when they take a turn for the worse does the topic suddenly come back into vogue. The third quarter of 2021 delivered a notably weaker performance than throughout the market’s recovery from the depths of the pandemic, so diversification is once again at the front of investors’ minds.

They are also warily eyeing the relationship between equities and bonds, which broke down in September, inflicting some of the largest losses for so-called “diversified” portfolios.

With the longstanding rules of diversification changing, investors are understandably nervous. Most asset classes have benefited for years from easy liquidity conditions. With an inevitable tightening cycle on the horizon, we could see most risk assets suffer. So how do you diversify against a murky economic backdrop marked by rising inflation, paltry growth and the very real risk that central banks get it wrong? Here are three tactics to consider.

The merits of cash

Bull markets typically start from a point of very low valuations, when investor optimism has been hit by a war, recession or crisis and interest rates are low or falling. Today, none of these factors apply. Valuations are high, as are profit margins, and interest rates are on the turn.

In these circumstances, fund managers are increasingly pointing to the merits of a higher short-term cash allocation as “the least worst option”. There’s no disputing that cash has been a terrible long-run investment (except in Japan). But, as Morgan Stanley points out in its recent research note Cash Isn’t Trash (For Now), the situation over shorter time horizons is different. Since 1959, the probability of cash outperforming the S&P 500 in any month is 40 per cent, and one in three over any six-month period.

One of the most common arguments for being bullish on almost any asset is that it will be more appealing than holding the alternative: cash. But while the “cash is trash” mindset is catchy and persuasive, as the research from Morgan Stanley explains, it can also be misleading. The argument mixes the long term (where cash usually loses) with the short term (where its record is far better). It frames cash as the “alternative” when, in reality, the trade-off is rarely that binary.

With inflation in the UK likely to be more sticky than transitory — courtesy of Brexit, Covid-19, higher energy prices and a lack of clarity on the state of the UK labour market — fund managers are turning away from sterling bonds and instead choosing to hold that money in cash.

“Cash is a very good diversifier to have in the short term,” says David Coombs, head of multi-asset investment at Rathbone Unit Trust Management. “Clearly you lose money in real terms, if inflation is high, but over the next few months having a significant cash weighting is a very good idea.”

Most assets are better than cash most of the time, but cash can outperform in the short run. A strong argument to hold (some) cash is that it will return more with less risk. Of course, this isn’t an all or nothing argument. After all, fund managers are given money to invest, not to park in a bank. But some allocation to cash can act as a small flexible buffer — think around 5 per cent to 10 per cent — and as a war chest to buy into market dips.

Only the bold hold gold?

With confusion on the outlook for inflation likely to spill into bond and equity markets, stoking volatility, many may turn to gold as the port in a storm. Gold is touted as the ultimate diversifier — the place to be when inflation goes up or the world goes to pot. But anyone who’s held gold (present self included) will be woefully disappointed with the “protection” the yellow metal has delivered.

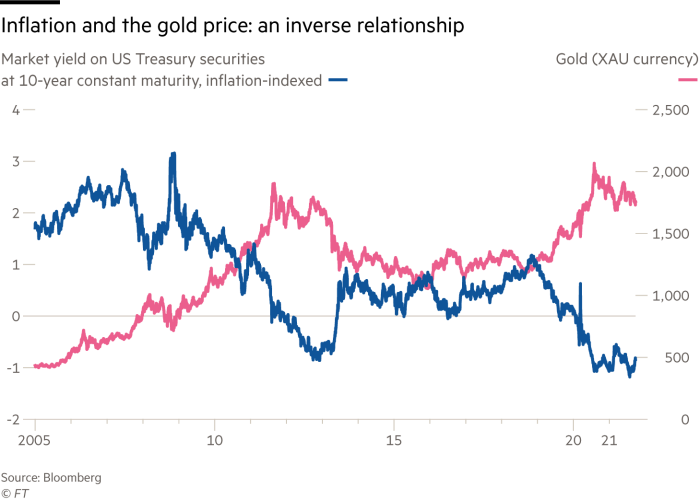

The truth, though, is that gold has done exactly what it is supposed to do. The gold price falls when interest rates are likely to rise. As the chart below shows, there’s a very strong inverse relationship between gold and real interest rates. This means that gold is not an inflation hedge, despite everyone touting it as such. Put differently, gold is not a good diversifier when interest rates are rising.

The big question is whether interest rates will rise. They shouldn’t, but that doesn’t mean they won’t. The Bank of England or the Fed may start raising rates in response to inflationary trends, when factors such as rising energy prices are in fact disinflationary — since they reduce an already conservative consumer’s discretionary spending.

Raise rates too soon, and there’s the danger of creating a recession at a time when the economic fallout of Covid has not dissipated and deeply indebted governments are spending money like there’s no tomorrow.

There is a very real risk that central banks miscalculate on rates, not least because there are no economic parallels in history on which to base their assumptions. The bottom line is that, while gold is probably not the answer, government bonds most definitely are not.

They can’t print food — or oil

It’s not just markets that are likely to be choppy. You don’t need to be a meteorologist to see more volatility in the seasons too, which will have an impact on agriculture. Introducing “soft commodities” such as wheat and corn as diversifiers into your portfolio may be challenging given the complexity of commodity futures prices, but you could introduce these via exchange traded funds.

Another alternative is agriculture equities. You can find a flavour of these among the top five holdings in the MSCI Global Ag ETF with names like Deere, Nutrien, Archer Daniels, Corteva, Kubota.

Finally, if the past few weeks have taught us anything, it’s how reliant on oil the world remains. Whether it’s Russian gas pipes, Middle Eastern unrest, or Brexit/Covid-induced labour market shortages, political instability means oil remains a constant risk and one to diversify for. Rising energy prices are a massive tax on growth, which means every well-diversified portfolio should have some exposure to oil and gas.

Of course, the time to buy oil was 20 months ago, when the price was depressed. But that’s the point about diversifiers: you need things in your portfolio that are going down when everything else is going up. That’s what diversification is, and it always comes at cost — much like insurance. You might not need it at the time, but when you eventually do, you’re always happy you paid for it.

Maike Currie is head of personal finance and markets content at Fidelity International. Maike.currie@fil.com, Twitter @MaikeCurrie; Instagram @MaikeCurrie. She has holdings in the BlackRock Gold & General Fund and the Ninety One Global Gold Fund.

Comments