What is an ethnic minority anyway?

Simply sign up to the Social affairs myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Rishi Sunak confuses people. They struggle with how exactly to quantify his place in British and global history. Some, forgetting Benjamin Disraeli, dub him the UK’s first “ethnic minority” prime minister. Others, who remember Disraeli, but don’t want to break up the flow of their sentence, call him the UK’s first “non-white” prime minister.

It’s a funny definition, “non-white”. Almost everyone is “non-white”: with the exception of a very few, the lightest-skinned person you will meet will only be about as pale as, say, a tin of “natural calico” Dulux paint. What we really mean is that there is some quantifiable difference between the experience of “white” people, regardless of whether they are part of an ethnic and social minority, as Disraeli was, and that of “non-white” people.

Is this right? Not necessarily. In the UK, according to the government’s race disparity audit, the ethnicity that currently has the worst outcomes, across employment, life expectancy and access to basic goods and services, are those from a Gypsy Roma or Traveller background: a group that we would, for the most part, class as “white”.

The reason why this matters is that how a state defines the ethnicity (or lack thereof) of its people is intimately linked to its ability to provide adequate services and to identify its own shortcomings. In Canada, the state created the term “visible minority”: those the state defines as “visible” minorities can benefit from affirmative action policies, alongside indigenous Canadians, women and people with disabilities. Anyone who falls outside those groups can’t.

Part of the problem here is obvious: who, exactly, defines what a “visible” minority is or isn’t? A Jewish-Canadian may or may not be a “visible” minority for the purposes of the Canadian government, while being all too “visible” as far as an anti-Semitic employer is concerned.

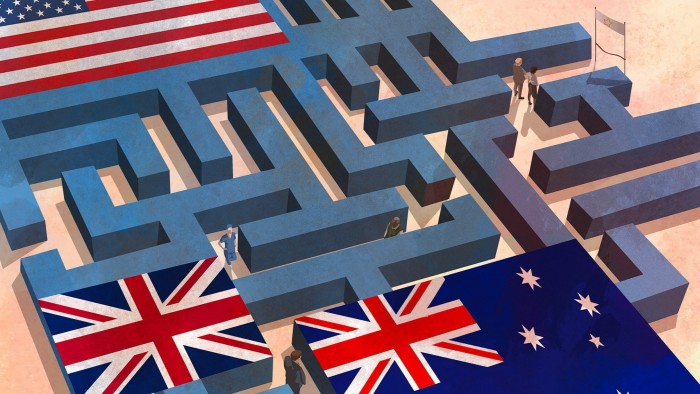

The long and disreputable history of immigration policy shows us that what states and people class as “visible” or “non-white” is continually in flux. One of the first bits of border control legislation in the US, in 1875, was designed to combat what Ulysses S Grant described as the “evil” of “the importation of Chinese women . . . few of whom are brought to our shores to pursue honorable or useful occupations”. This was targeted at “visible” minorities. But by the 1920s, US immigration legislation extended to include purportedly “invisible” minorities from southern and eastern Europe.

“White Australia” policies, which the historian Andrew Rosenberg dubs “the world’s most racist immigration policies” in Undesirable Immigrants, were broadly welcoming to all European immigrants at the expense of non-European immigrants. Speaking in opposition to the measures in 1901, the Labour politician King O’Malley warned that the bill’s educational test “will not shut out the Indian ‘toff’ who becomes a human parasite preying upon the people of the country”, or the “intellectual Afghan”.

The rationale in both countries had a shared reasoning: in the US, Italian and Jewish immigrants were excluded in order to “keep America white” while in Australia, the same groups were included in order to maintain Australia’s whiteness.

The reality, revealed most starkly by immigration policy but which is equally true in a workplace or a playground, is that your minority status is largely something that is done to you rather than how you feel yourself. Many Italian immigrants who found themselves barred from the US by the 1924 Act would have felt themselves to have a shared “race” with the Americans who excluded them, and not much in common with the Jewish immigrants they were excluded alongside. (And indeed, vice versa.) But the self-declared ethnic status of these individuals ultimately proved secondary to how states chose to identify them.

The action of past governments matters a great deal in the present. You probably owe at least some of your successes or failures to what happened to your parents and indeed your grandparents. In assessing current outcomes, we are almost certainly missing social problems if we ignore how governments acted in the recent past.

So how should states measure diversity and difference? This is one area where the UK has roughly the right approach: instead of dividing people into “visible” minorities or not, the essence of UK equalities law is that “protected characteristics” apply to everyone. It is illegal to discriminate against these characteristics, whether based on age with a worker in their twenties or late sixties, or based on race against someone who is “white” or “non-white”. Equally importantly, the law allows measures like affirmative action and recruitment to be flexible rather than being stuck with a 1920s, 1970s or even 2000s conception of who is being held back.

Comments