Italian women cultivating a life in winemaking

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In 1385, when Florence was emerging as a Renaissance centre of banking, commerce and art, Giovanni di Piero Antinori was admitted to the city’s winemaking guild — laying the foundation of what is, today, one of Italy’s oldest and biggest family-owned wine businesses.

For 25 generations, the Antinori winemaking operations passed from father-to-son in the family’s stronghold of Tuscany — terrain of the Sangiovese grape that produces Chianti Classico, one of Italy’s best-known wines.

But, these days, the family business, Marchesi Antinori — which has more than 3,000 hectares of vineyards on 26 estates in Italy and overseas — is run not by a male dynastic scion, but by the three Antinori sisters, led by the eldest, Albiera, the company’s president.

She is among a growing contingent of women in leadership roles in Italy’s €13bn wine industry. “My father did not have a son — that made things much easier,” says Antinori, who started working in the winery just out of school in 1986. “Coming from a very traditional family with a long history, it could have been an issue to think about a girl or woman working in, and possibly in the future even leading, the company. But life is such.”

Traditionally, Italian winemaking, like most Italian agriculture, had been a male preserve. In the 1990s, though, women began making inroads, as young men from rural landowning families chose to pursue careers in cities.

“The countryside was not on the priority list of first male children, who were going to work in finance or other situations,” says Antinori. “The countryside was given to daughters [who] showed interest. Nobody else wanted to look after it.”

Now, Le Donne del Vino, or Women of Wine — founded in 1988 for the handful of women then in the wine business — has more than 1,000 members. They range from the inheritors of established family estates to critics and sommeliers, and entrepreneurs who founded their own wineries.

Women’s growing influence comes as the industry confronts the impact of climate change, demands for more sustainable practices, and concerns over the next generation’s willingness to take charge of family-owned wineries.

“It’s a poetic business, but it’s tough,” Antinori says. Yet she sees women bringing a greater sense “of stewardship” to the wine world.

Marchesi Antinori currently produces more than 20mn bottles of wine a year, under 100 or so labels. But Antinori, whose 84-year-old father Piero remains active as honorary president, says “the priority is not to get maximum turnover, or maximum earnings but rather to ensure sustainability — whether that means planting trees, controlling erosion or avoiding overproduction.

“For us, the priority is to pass the land that we are taking care of in a better condition to the generation after,” she says.

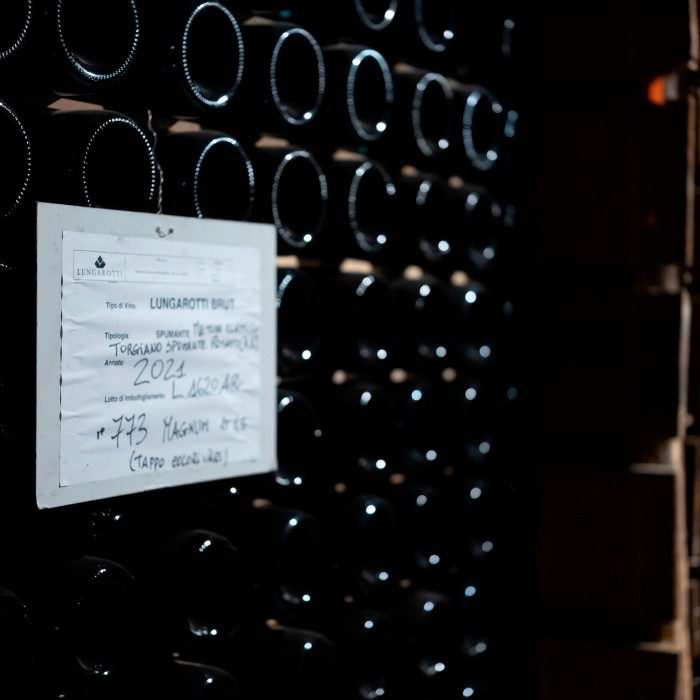

Chiara Lungarotti, chief executive of Umbria-based Lungarotti, was left in charge of the family winery in 1999, aged 27, after the death of her father.

She felt great pressure to ensure the survival of an estate that her father had transformed from a traditional, multi-crop farm into a dedicated winery.

“The responsibility went from his shoulders to mine,” she says. “My first fear was for all the people working for us, to enable them to go on with their jobs and their lives.”

Despite her degree in viticulture, Lungarotti faced resistance to her attempts to introduce modern agricultural methods to a farm that was still following traditional practices.

Her insistence on removing some grape clusters from vines to allow the best to grow bigger and healthier caused an uproar among the older, male workforce, she recalls. “They were saying ‘she is crazy — she is throwing away the fruit. This estate can’t have a future’.”

Today, with a new generation more receptive to modern techniques, Lungarotti continues to explore more sustainable methods of cultivating her family’s 250 hectares of vineyards, which produce around 2.5mn bottles a year in total. Some 20 hectares of the vineyards are cultivated entirely organically.

“We need profit at the end of the year because, without profit, there is no future,” says Lungarotti. “But the profit has to be reinvested in the estate.”

Reducing ecological impact is also a preoccupation for the four sisters running Bortolomiol winery, founded by their father, in Valdobbiadene in the hills of Treviso — the heart of Italy’s prosecco-producing region.

The family cultivate their own six hectares organically, while the 60 other viticulturalists that supply grapes to the winery must follow strict green protocols limiting use of chemicals. Carbon emissions are being tracked in collaboration with a university, and the estate aims to reach net zero emissions from all operations by the end of this year. “We want a balance between agriculture and the environment,” says Elvira Bortolomiol, vice-president. “Today, sustainability is a fact in the vineyard and in the winery.”

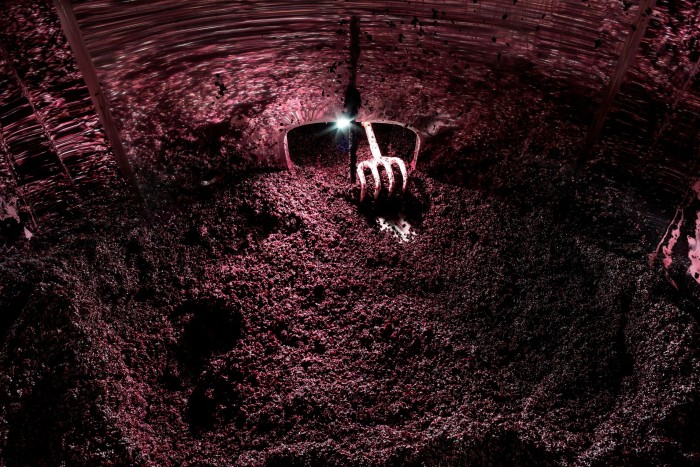

Arianna Occhipinti, founder of an eponymous wine label, is one of Italy’s few self-made women winemakers, having started her own winery in 2004, aged 21, on a single hectare in Sicily.

The daughter of an architect and a schoolteacher, Occhipinti encountered the wine business at 17, while helping her uncle — who founded his own winemaking business — at an event. “People were working and doing business — but smiling,” she recalls.

She went on to study viticulture and oenology, which she says, “opened the door to the world of production — the world where men predominated”.

Initially, she expected to work for her uncle, or another estate. Instead, her passion for artisanal, natural winemaking based on organic agriculture, and a desire to return to her native Sicily — where many were abandoning older vineyards — led Occhipinti to go it alone.

“My goal is never the wine at the end, but why I am making wine — to do something for my territory, with wine that has come from very sustainable . . . agriculture made by artisans,” she explains.

For €1,000 a year, she rented her first hectare, while her parents guaranteed her first €50,000 loan to invest in production. She also received funds from an EU programme designed to help Italy’s less developed regions.

Today, she grows wine, olives, fruit and vegetables on 30 hectares, employs around 25 people, and produces between 140,000 and 150,000 bottles following her cherished principles of organic, natural production.

She also mentors women who are thinking about entering the world of wine, with advice that “the best thing is to start from a small project and grow with it step by step”.

But she remains frustrated by the paucity of women following her entrepreneurial path. “It’s too slow,” she says. “We are in a moment where more and more women can do this. But they are not arriving.”

Comments