The vineyards given a modern makeover by world’s top architects

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Traditional images of vineyards generally feature a historic château but contemporary architecture is gaining a foothold in this conservative industry, and modern winery buildings are now becoming cutting-edge cultural attractions.

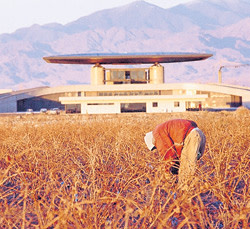

Some of the biggest names in architecture have added a vineyard to their portfolio in the past decade: Frank Gehry and Renzo Piano have both created vineyard structures that double as exhibition spaces; Argentine firm Bormida & Yanzon has gained a global reputation thanks to its creative designs for vineyards in Mendoza such as O. Fournier; and Herzog & de Meuron is responsible for one of California’s most architecturally interesting wineries.

Europe, and Spain in particular, is pioneering some of the most innovative designs. Some have compared the Faustino Group’s Bodegas Portia in Ribera del Duero, the work of Foster + Partners, to a spaceship. The building’s sloped, tri-part structure was designed to work with the local topography and to appear unobtrusive from ground level. Also notable are the five terracotta-clad arches of the Bodegas Protos, in nearby Peñafiel, east of Valladolid, which were designed by Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners to blend aspects of traditional build style with modern winemaking techniques.

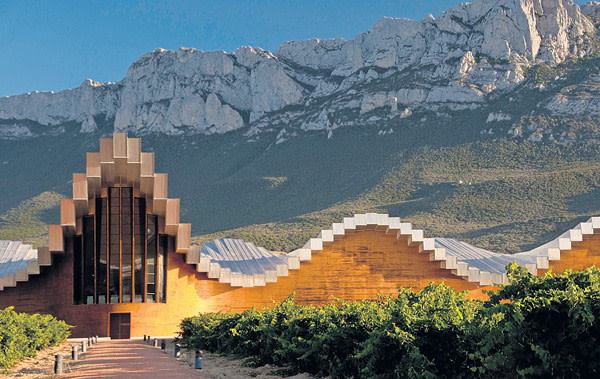

Star names in the Rioja region include Spain’s Santiago Calatrava, who created the dramatic Domecq-owned Ysios winery, which, with its rippled, crenulated roof, sits within the landscape like a row of giant wine casks. Zaha Hadid, meanwhile, has designed an elegant tasting room at the Bodega López de Heredia.

Juan Manuel Herranz, partner in Spanish architectural firm Virai, believes the trend for landmark architecture represents the natural affinity the wine industry has with wider culture. “Wine is generally associated with high cultural values, which complement other areas, such as appreciation of art, the environment and architecture,” he says.

Herranz’s firm was responsible for the pared-back modernism of the La Grajera winery in Rioja, which was completed in 2011. Virai was tasked by the local government with creating a space that was practical, sustainable and at one with the landscape. The result draws on both urban and rural influences: the administrative and educational building is clad in earth-coloured ceramic panels while the production facility and cellar, which is part subterranean to ensure consistency of temperature, is of local sandstone and designed to mimic a vineyard’s retaining walls. “The investment in striking buildings that work with the surrounding space and landscapes is also part of the move towards an industry that has been modernising overall,” says Heranz.

Italian companies are also exploring high-concept design and sophisticated technology, while also aiming to safeguard the environment of their vine-growing regions.

Renzo Piano’s design for La Rocca di Frassinello, the Tuscan vineyard owned by Italian media tycoon Paolo Panerai, is a prime example. The building – a low, sprawling ensemble of terracotta render, steel-mesh panels and green shutters – sits just above the vines and rolling hills and is given definition by a slim tower. The use of traditional Tuscan colours and materials gives the design a timeless feel, although it was completed in 2007.

“Piano didn’t want to make a monument to himself, or to the owners, but something very connected with the landscape,” says Massimo Casagrande, the estate’s winemaker.

The remodelling of wineries is often done to conceal the production processes. La Rocca’s barriquerie (barrel room) was designed by Piano as a broad subterranean amphitheatre that is also used for musical events.

Similarly, at nearby Le Mortelle, owned by the Antinori family, the winemaking operation is half-hidden underground to minimise its visual and environmental impact. The design, by Italian firm AEI Progetti, involved carving out an atrium 40 metres in diameter and 25 metres deep. A wide spiral staircase descends three levels, past gravity-operated production vats, to a dramatic cellar within the bedrock. This space, where the ideal temperature for wine storage is maintained, provides an unusual location for the all-glass tasting room.

With so many vineyards now competing for tourism, a dazzling new design by a well-known architect may also be a sound commercial decision. Amid the Riojan vines and 19th-century cellars of Marqués de Riscal, for example, a hotel designed by Frank Gehry in his elaborate signature style has become a big draw for visitors.

Château La Coste in Provence, France, owned by Irish businessman Patrick McKillen, has taken it one step further. Visitors to the 200-hectare site can wander among works by artists Tom Shannon, Andy Goldsworthy and Louise Bourgeois, as well as several Pritzker Prize-winning architects. Gehry designed the music pavilion, while French architect Jean Nouvel created the winery and cellar buildings, a pair of semi-cylindrical structures in polished aluminium.

“It’s a beautiful building, filled with light, but also practical,” says Daniel Kennedy, art manager of Château La Coste. “We needed to update the vineyard facilities and consulted experts on ensuring the space would be functional as well as aesthetic.”

Inevitably, some oenophiles wonder if the passion for high-concept architecture risks overshadowing the wine. Christian and Cherise Moueix, owners of the Dominus vineyard in California’s Napa Valley, were ahead in the game when they commissioned Herzog & de Meuron to design their new winery in 1997. Their primary request was that the building be “invisible” and Cherise says they chose the Swiss firm “not in order to make an iconic architectural statement but for their rigorous approach, ability to deliver the best tool for producing wine, and their sensitivity to the landscape”. The result, a simple gabion structure of steel baskets filled with local basalt rock, is beautiful but also functional, in that it helps to regulate the internal temperature of the winery. “The winery blends so well into the surrounding vineyard, Christian’s wish has come to fruition,” says Cherise.

What the couple did not anticipate was the level of global interest the winery, which is closed to the public, would generate. “The building’s ‘immateriality’ has drawn enormous attention,” says Cherise. “So, the exact thing we had hoped to avoid has come about: the winery has taken on more importance than the vineyard.”

Comments