How Deutsche Bank’s high-stakes gamble went wrong

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

It was the Friday before Christmas and Edson Mitchell, boss of Deutsche Bank’s London-based investment bank, was rushing home to see his family in Maine. By 5pm he was on the home stretch: his private plane had left Portland. By 5.15pm it was within sight of his destination, Rangeley airport. A minute later, in a swirl of cloud and snow, the aircraft slammed into nearby Beaver Mountain, killing Mitchell and the plane’s pilot.

That was 17 years ago. What was a personal tragedy for Mitchell’s family, friends and colleagues would also mark a moment of upheaval for the bank he had transformed. To some fatalistic observers, the crash — and its accompanying heartache — presaged the troubles that Deutsche Bank itself has suffered in recent times.

Mitchell had been a brilliant trader and an inspirational manager who, in five years, helped remodel a sleepy German lender into a Wall Street dynamo. As a fast-living chain-smoker who would bet on anything from golf to gold, he also embodied Deutsche’s big-stakes gamble on global markets. In the world of roulette-wheel investment banking, Deutsche was the highest roller of all. And for a long while the punts paid off.

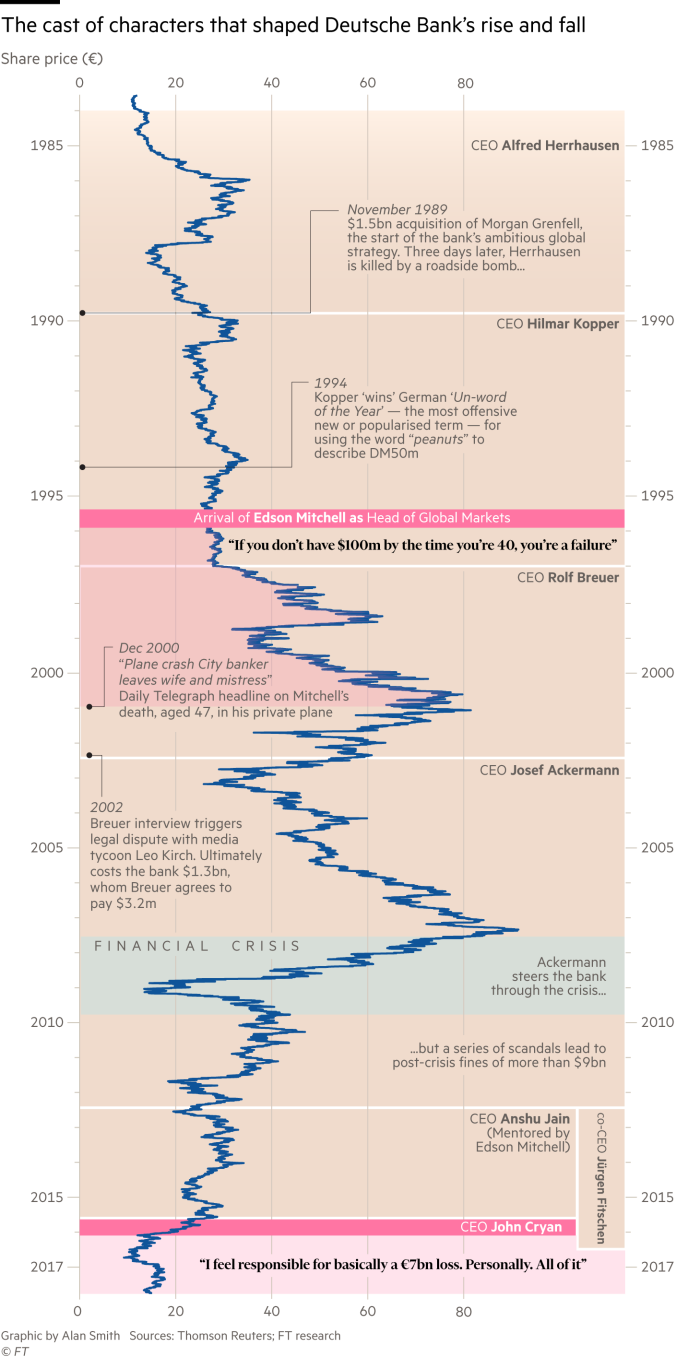

But for the past few years, despite emerging as an apparent winner from the 2008 financial crisis, Germany’s biggest bank has appeared locked in a downward spiral. Last autumn, the stock market’s alarm about the bank’s finances was so severe that investors and even government officials discussed the possibility of a bailout.

A recent note on the bank from analysts at Autonomous Research was titled “Beyond Repair”. “It’s obvious something has to be changed,” says one of the bank’s biggest shareholders. “They [Deutsche’s management] don’t understand the sense of urgency.”

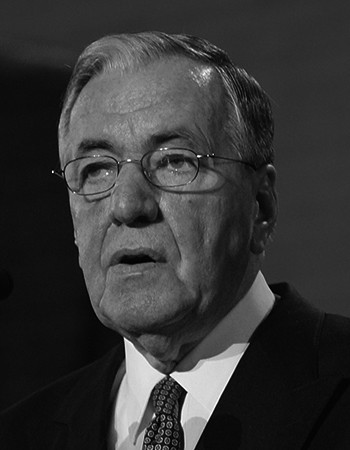

Chief executive John Cryan — a bluff Brit who is the antithesis of Edson Mitchell — is resolute. “I will carry on at least until my contract ends [in 2020],” he told the Financial Times. “At the moment the job is getting more fun every day. The heavy lifting is almost over.”

Yet existential questions remain. What should Deutsche’s future role be? Will the leading financier of Europe’s biggest economy retreat to its more modest roots? Is Cryan part of the solution or part of the problem?

Deutsche Bank’s journey — from a low-profit group focused on German clients and owned by German shareholders, to the epitome of global capitalism in the heady days before the financial crisis — is an extreme version of a path followed by many banks around the world. Its fate will hold lessons for lenders, governments and regulators as the banking industry continues its post-crisis evolution.

Back in 1995, Deutsche was a staid domestic lender led by Hilmar Kopper, a Prussian farmer’s son. Wall Street names such as JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs and Merrill Lynch were expanding aggressively, thanks to booming markets, the rapid growth of financial derivatives and the advent of electronic trading. A wave of deregulation led them to Europe en masse.

Deutsche was being left behind and Kopper was losing patience with the bank’s conservative ways. He felt humiliated in late 1994 when the German government picked Goldman Sachs, not Deutsche, to lead the global process of selling Deutsche Telekom — Europe’s biggest-ever privatisation. By the following summer he had hired Mitchell — a brash but brilliant banker from Merrill Lynch — to begin the process of turning Deutsche from prosaic corporate lender into one of Wall Street’s own.

For years, the strategy worked like a dream. Deutsche steadily sold off a DM24bn portfolio of corporate shareholdings, relics of its postwar role as a pillar of West Germany’s reconstruction effort. The proceeds were used to supercharge its investment bank: first, by integrating Morgan Grenfell, a tired London merchant bank acquired in 1989; then by hiring from rivals such as Merrill Lynch; and finally, by purchasing the troubled US group Bankers Trust in 1999.

Josef Ackermann, an ex-Credit Suisse banker, oversaw Deutsche’s investment bank before becoming head of the whole group in 2002 and leading it for the next decade. He remains proud of his achievements: “We seized the growth opportunities and within a few years built a top-three global investment bank.”

At its peak in the middle of 2007, Deutsche claimed the title of the world’s biggest bank, amassing total assets of close to €2tn. Many of the world’s finance houses had been growing at unprecedented rates, but Deutsche’s expansion was faster and more furious. By June that year it was increasing staff numbers at an annualised rate of 20 per cent and assets by nearly 50 per cent. Net profit was up by an annualised 60 per cent. Deutsche’s investment bank had all its chips on the table.

The financial crisis that took hold in the second half of 2007 and accelerated through 2008 left no global bank untouched. It was an undeniably painful period for Deutsche, with a €5.7bn pre-tax loss in 2008. But compared with some rivals, the German lender was able to shrug off the crisis.

Ackermann’s statesmanlike leadership helped, as did the foresight of trader Greg Lippmann, who bet so successfully against subprime mortgages that he became the protagonist of the Michael Lewis book The Big Short, inspiring the Ryan Gosling character, Jared Venett, in the hit movie of the same name. Other executives sold subprime exposures to rivals and bought insurance against default. And the US government’s rescue of AIG, one of those insurance providers, was worth an estimated $4bn to Deutsche.

But chutzpah, judgment and luck can only take you so far. What has puzzled many who admired the bank’s handling of 2008 was just how badly the past few years have panned out. As peers have prospered, Deutsche’s fortunes have cratered. Its shares have halved over the past five years, just as those of some US rivals have doubled in value.

Eric Ben-Artzi, an ambitious young mathematician who moved to the bank from Goldman Sachs in 2010, has an inkling why. “When I joined Deutsche,” he recalls, “I thought I was joining a winner, backed by a German notion of disciplined organisation.” That impression didn’t last. “Within months I was disillusioned,” he says. He ended up as a whistleblower, informing regulators about the way Deutsche valued and risk-assessed a vast portfolio of arcane derivative securities — $130bn of so-called leveraged super-senior swaps.

“They were doing some interesting academic stuff in terms of risk modelling,” Ben-Artzi recalls. “But it was like a façade. The methodology that was actually implemented came out of thin air.” In 2015 the affair landed Deutsche with a $55m fine for false accounting.

“I blew the whistle because I gradually came to realise that this bank was only semi-legal,” says Ben-Artzi, who now works for a fintech start-up in Israel. “It was partly fear and partly a moral conscience. This was [one of] the biggest banks in the world and I didn’t want to be part of it.”

What the Financial Times has discovered through dozens of interviews with current and former Deutsche Bank employees, investors and rivals, is that Ben-Artzi’s revelations reflect a broader truth about deep-rooted problems within the bank’s systems and corporate culture: issues that can be traced back to the aggressive beginnings of Deutsche’s investment banking expansion, first under Edson Mitchell and then through the era of Ackermann and his successor Anshu Jain.

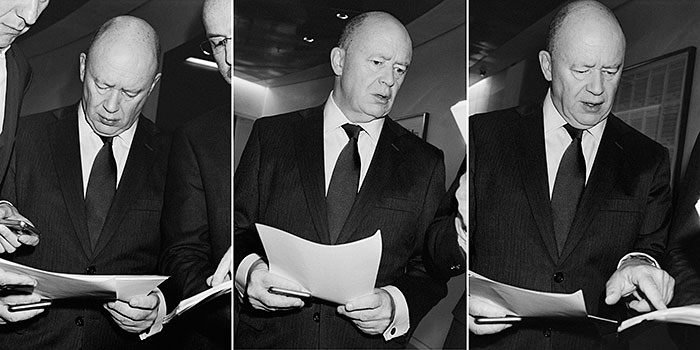

At college in 1970s Maine, Mitchell made a name for himself as a short but effective basketball player. When he opted for a career in banking, he took his competitive approach to sports into the trading room, and rose steadily through the ranks at Merrill Lynch. By 1995 Deutsche Bank had poached him to lead the buildout of the group’s still lacklustre trading operations in London. At the time, Deutsche’s investment bank was an amalgamation of a half-decent bonds business, plus a hotchpotch of operations inherited from Morgan Grenfell, the seed for Deutsche’s investment banking push sown by Kopper’s predecessor, Alfred Herrhausen.

In 1998, under pressure from Mitchell, Deutsche launched another bold move. “We had an off-site outside Rome that year,” remembers one senior manager. “And the message from Edson and his allies was clear: ‘If you don’t get stronger in the US, we will leave [the firm].’”

Within months, Deutsche had snapped up Bankers Trust, fresh from a corporate fraud scandal in which senior executives at the US group had shifted dormant customer money into the bank’s own coffers. Older hands on the board were concerned about the drift from Germany and the influence of unhealthy Anglo-American ways — but Deutsche’s globalising investment bankers prevailed.

Many who worked with Mitchell praised his technical abilities and ambition. “Mitchell was talented and aggressive,” says one former board member. Most of all, he enthused people. When he left Merrill for Deutsche, 50 colleagues followed. Rajeev Misra, who used to run Deutsche’s credit, commodities and emerging markets units and now heads SoftBank’s $100bn Vision Fund, was one of his disciples. “Five minutes with Edson and you’d walk out passionate about building a global bank. He had such optimism — the glass was always half full.”

But Mitchell’s appetite for risk was prodigious. “He had Wild West attitudes,” remembers one senior executive from that era. “[We] really had to manage him closely. If Edson had lived and become CEO maybe Deutsche would have blown up in more dramatic fashion in the crisis.”

Mitchell was only at Deutsche Bank for five short years but he left a long-term legacy. Deutsche’s investment bank became aggressive, Anglo-American, bonus-hungry and so bent on growth that regulatory relations were pushed to the limit and integrity was sacrificed. As at other banks at the time, some executives’ personal behaviour became increasingly excessive, if not out of control.

There was Mitchell’s own unconventional lifestyle — a live-in mistress at his lavish London villa, the family back home in Maine. Other managers engaged in petty corruption for personal gain, two bankers familiar with the period told the FT, including owning companies such as a limousine operator, to which they outsourced Deutsche service contracts. Sexism was rife — a busload of escort girls were once invited to a Christmas party and serviced male staff in a VIP suite. Cocaine habits were commonplace.

After Mitchell’s death, his protégé Anshu Jain, a fiercely bright pioneer of derivatives trading, was elevated to run the markets business, then the investment bank and, eventually, the whole of Deutsche. Born into the ancient Jain religion, the banker — a vegetarian and a refined family man — looked like a sharp contrast to his former boss. What united them was a fascination with the complexities of finance and a reverence for the sums of money it allowed banks and bankers to earn.

At his peak, Jain was among the best-paid financiers in the world, earning up to $30m a year, according to colleagues. As Deutsche sought to lure staff from rivals, it became known for its generous pay deals, with top traders routinely earning $10m-$20m.

Many who joined Deutsche Bank in the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s speak of it as an “inspirational” place to work. Creativity was encouraged, results were rewarded and ambition — and risk appetite — seemed limitless. But there was a downside. “Deutsche always hired mercenaries into the investment bank,” recalls one former senior executive. “They didn’t care about ethics.” Internal competition for the same client business was encouraged on a “may the best man win” basis that could lead to toxic dynamics. “It was a mishmash of cultures,” recalls one former executive.

Behind that lay the bank’s rapid growth, the acquisition of two brokerage firms besmirched by ethical scandal and the mass import of teams of bankers from various rivals. Bosses in Frankfurt were so blinded by the success of the unit that they invested in little else. But they also failed to control it with an effective compliance function or responsive information systems. The result was great success in the boom years and deep problems ever since. It has given the current chief executive a mammoth turnround task.

John Cryan is the third non-German investment banker in a row to take Deutsche’s helm. But the dry-witted northerner who took over in July 2015 is as different from his predecessors as you can imagine. He is plain-speaking, cultured (with a passion for classical music) and geeky (he talks knowledgeably about Deutsche’s computer code and, says a friend, once helped builders rewire his London home).

Where the old Deutsche Bank stood for big bets on the markets and big bonuses to match, Cryan has stripped back high-risk business and slashed bonuses. Soon after his appointment, he said: “I have no idea why I was offered a contract with a bonus in it because I promise you I will not work any harder or any less hard in any year, in any day because someone is going to pay me more or less.”

Last year, Deutsche took the unprecedented decision to axe virtually all bonuses due to poor results. (There were “retention payments” for 5,522 “mission-critical people”.) “It was probably one of the most difficult decisions we took,” says one board member.

The lender’s previous bonus culture was hardly unique among peers. But its mismatch with performance was acute. Over the 1995-2016 period, shareholders earned a net €17bn from owning Deutsche, once dividends, share buybacks and increased stock market value are offset by capital increases. That is dwarfed by the €71bn paid in bonuses over the same time period. One top investment banker from Deutsche’s mid-1990s build-up phase, confronted with that statistic, appears uncharacteristically humbled. “Would the bank have been better off without hiring any of us?” he asks with a look to the middle distance.

For some staff, Cryan’s abstemious rhetoric rings hollow — his wife is a member of the billionaire Dupont dynasty. His core integrity, though, is hard to doubt. Former colleagues remember that during his work as an adviser to ABN Amro in 2007, the then UBS deals banker informally told Royal Bank of Scotland, ABN’s ultimate acquirer, that it should think twice about pursuing the €72bn acquisition. It was a deal that ended up destroying the now largely state-owned RBS. “He’s very honourable,” says a friend and former colleague. “He’s certainly not afraid to tell someone to abandon a plan even if it loses him business.”

Cryan’s attempts at reform sometimes verge on the sanctimonious. His refusal to meet Deutsche’s new leading shareholder — controversial Chinese conglomerate HNA — caused some friction with Paul Achleitner, the bank’s supervisory board chairman. But Achleitner, who ousted Jain to make way for Cryan, is unfazed. “John has the intellect, the dry sense of humour and the ability to call a spade a spade,” says the chairman. “That’s extremely healthy. He’s brought people down to earth from too much hype. Are bankers demotivated by that? They need to wake up and smell the coffee. He’s genuine and that’s a huge attribute in today’s world.”

Cryan has begun to change Deutsche’s substance as well as its style. Cutting costs has become one of the biggest priorities, echoing his work at UBS when as finance director up to 2011 he oversaw a near-40 per cent reduction in overheads. Deutsche’s bloated cost base — accumulated with little thought in the boom years — is still stubbornly high today. At the last count, it absorbed more than 80 per cent of revenues, double the tally of some banks. Breakneck growth in the boom years left the group with what several insiders have called “spaghetti infrastructure”. At its peak, the bank used 6,300 risk models and 108 trading systems.

Cryan is convinced the scope for savings is bigger than at UBS. “Here the cost-cutting is more straightforward because it’s an avoidance of duplication,” he says. “We employ 97,000 people. Most big peers have more like half that number.”

Trying to pin him down on how exactly such advances might be achieved is challenging — he is prone to uninterruptible monologues about technology’s advantages, with tangents on subjects such as why Python programming is hardly a “growth area”. In interviews for this article, Cryan spent more than a third of the time talking about technology.

Operations chief Kim Hammonds, an engineer who previously worked for Boeing and Ford, is a key ally, who has made Deutsche’s systems safer by “insourcing” thousands of jobs previously done by contractors. “At Ford I used to design frame and fuel systems,” she says. “Things must work. It must be safe.” She has also been retiring outmoded technology — including cutting the number of payments systems from more than 40 to just eight.

Yet analysts remain unimpressed. Autonomous Research’s report identified Deutsche’s laggard spending on technology — equivalent to about half the outlay of US rival JPMorgan — as the main reason for its bearish conclusion about the bank’s future.

If cost management and technology investment were neglected in Deutsche’s headlong race to expand a decade and a half ago, so too were the bank’s financial foundations.

Its biggest weapon pre-2008 — and its biggest weakness post-crisis — was its unparalleled use of “leverage”. Few other banks used so much borrowed money, as opposed to shareholders’ equity, to support their growth. Borrowing has been generally inexpensive for 15 years, thanks to central bankers. But it was exceptionally cheap for Deutsche Bank, which could once borrow money for little more than the AAA-rated German government.

This substructure has steadily crumbled away. “Deutsche was like a sandcastle all built on leverage,” says a rival. Borrowing costs spiralled following credit rating downgrades. Under pressure from regulators, the bank has had to raise €33bn of fresh equity since 2008, more than any non-nationalised rival.

Back in the boom years, guarding against bad behaviour was low on the priority list too. “When I joined the bank in the 1990s, people had PCs on their knees,” recalls one former board member. “It’s astonishing we never had a Nick Leeson incident,” he adds, referencing the rogue trader who brought down Barings Bank in 1995. “The IT systems, the accounting, the controls, had had very little investment.”

When Lehman Brothers and others collapsed in 2008, Deutsche battled on. But its systems creaked. “There were so many pockets of things being broken. You felt exposed as a firm,” says one trader who joined after the peak of the crisis. “When issues were found,” he adds, “the approach was ‘how much are we going to get fined?’” If the sum wasn’t astronomical, the bank’s management appeared willing to run the risk.

In April 2015, the bank was handed a $2.5bn penalty as part of the sector-wide probe into the rigging of the Libor interest rate mechanism. Other banks were fined, too, but Deutsche incurred an extra penalty for being uncooperative. In a damning report into the bank’s culture, Germany’s financial watchdog BaFin suspected Deutsche’s then chief Jain of misleading regulators, contributing to his departure that summer, though BaFin’s president later retracted the suggestion.

One insider says Deutsche’s typical approach to regulatory investigations was to invoke rights such as bank secrecy and data protection to avoid handing over documents. Often the protections didn’t hold up and Deutsche had to disclose the information anyway, but was viewed as obstructive by investigators.

Insiders say the bank’s attitudes have matured with new management. “I like to think our relations with regulators have improved.” says Sylvie Matherat, the chief regulatory officer who was hired from the Bank of France in 2014. “We’re very transparent. We don’t hide anything.”

One ongoing legacy issue relates to Deutsche’s relationship with US President Donald Trump. The bank’s long-time role as a key lender to Trump and his property-development businesses is under investigation by Robert Mueller, the special counsel who is probing possible collusion between Trump’s campaign and the Kremlin. Deutsche has not commented publicly on the issue but has conducted an internal inquiry into rumours of its involvement in suspicious links between Trump loans and Russian banks.

People close to the relationship said more than $300m of loans were outstanding to Trump, but the bank’s probe found no improper Russian connections. Deutsche insiders said the bank was keen to be subpoenaed by Mueller in order to dispel the rumours.

Cryan’s practice of preaching decency, outlawing mercenary attitudes and working with, instead of against, regulators has won over some early sceptics. “I thought we needed a leader when Cryan was hired that was much more inspirational: take to the hill, go, go, go,” recalls one US-based banker. But he now sees Cryan’s directness as a “massive breath of fresh air”, crucial to resetting ethical standards and avoiding further scandals.

Not everyone agrees. Cryan’s sombre bluntness “can be very depressing”, complains an executive. It grates particularly with some of the group’s investment bankers in the US. “The parsimonious hair-shirt style is bad for morale and performance,” says a senior banker who used to work with Cryan.

Whatever the merits of last year’s bonus cull, it has compounded the departures of previous years. “There are pockets where we’ve definitely lost more people than we hoped,” admits a senior banker with global responsibility. James Chappell, analyst at Berenberg, says: “Cryan is almost too honest. It’s not good for morale. There’s a phalanx of people interviewing [for jobs] with rivals.”

Critics make an unflattering connection between the chief executive’s rhetoric, key staff departures and a collapse in investment banking revenue — from an average of €6bn a quarter before he took over to about half that today. Cryan insists some of that business was low-margin and unattractive. Other activities that made money in the past were questionable on other grounds. For example, Deutsche’s Russian investment banking business was closed down in the autumn of 2015, following the discovery of “mirror trades” allegedly used to launder $10bn out of Russia. The trades were the subject of a $630m settlement with US and UK regulators this year, and are still being investigated by the US Department of Justice.

Executives say one of the biggest causes of revenue decline was a late 2016 wrangle with the DoJ over the bank’s punishment for its alleged mis-selling of mortgage securities pre-2008. The final $7.2bn settlement removed one of the biggest remaining legacy issues, giving investors the confidence to put up €8bn of fresh equity, thus silencing any suggestion that Deutsche might not survive.

But a leaked opening demand of $14bn a few months before did huge damage. Fears about Deutsche’s ability to withstand such a penalty had a direct impact on client trust, especially with hedge funds, which withdrew deposits en masse. “We gave up ground [to the big American banks] because of the damage that our brand suffered,” says one top trader. Markets boss Garth Ritchie admits that these days, with ambitions shrunken, “we don’t see Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan as like-for-like competitors”.

Investor opinion on Deutsche Bank is now pretty downbeat. In a September credit rating downgrade, Fitch predicted a decline in net profits under the weight of ongoing restructuring. Ritchie is defensive. “When you tear your hamstring, you have to go through rehab,” he tells the FT. “You can’t get back to racing immediately.” The problem is that the bank does not seem to know which race it wants to enter, or even whether it should compete in track or field.

Deutsche’s partial retreat from investment banking is not unique among European banks. But others had clear strengths to fall back on — in wealth management (the Swiss) or credit cards (Barclays). Deutsche’s room for manoeuvre is less obvious, with a second-grade wealth operation and a domestic retail banking market that is notoriously low-profit, dominated as it is by state-run savings banks and co-operatives. The pedestrian business of lending to corporate Germany was the fate Kopper was desperate to escape.

Asked to define the essence of the bank’s ambition, Cryan says, after a pause: “If we have a core DNA it’s payments and collateralised lending” — two of the more humdrum parts of banking. It is a pretty uninspiring raison d’être compared with the “world’s biggest fixed-income house” accolades of a decade ago.

It may, though, be realistic. One senior investment bank executive from the lender’s heyday says with regret: “Deutsche Bank came from mediocrity and it’s heading back to mediocrity.” Like many global banks, it has learnt that the success of the boom years was founded on precarious financing and abusive behaviour. But Deutsche is finding it harder than others to fix on a sustainable model for the future.

Some, including Cryan, urge patience. The bank has a plan through to 2020 to revive profits and generate a return on tangible equity of 10 per cent, compared with 4 per cent now. A flotation of the asset management division, slated for early 2018, is the next big step. Ingo Speich, portfolio manager at Union, a Deutsche shareholder, admits that “what went wrong in two decades, you can’t put right in two years”. All the same, he has suggested that unless Cryan shows progress in the next few months, “pressure will mount on management”.

Other investors privately go further. One top 10 investor has signalled that it plans to call for a confidence vote in Cryan at next May’s annual shareholder meeting. Even friends of the CEO doubt he can stay until 2020. “The big trouble is John doesn’t have a vision,” says one. “In 2015 he was the antidote to take the poison out of Deutsche Bank. And he was appointed in the nick of time. But he’ll go — there is pressure from the board, from shareholders, from staff. I’d be surprised if he was still there this time next year.”

So much for Cryan. What of Deutsche? Its home market, to which it is to some extent retreating, has always had a difficult relationship with its biggest bank. “Germany is not a country for financial services,” says a former government minister who has also worked in finance. “Investment banks are like weapons producers or cigarette companies in societal terms.”

But surely Europe’s biggest economy needs a global bank to link its companies to the world’s capital markets for equity and debt — perhaps with less ambition than it once had but more than it seems to have today? That is certainly chairman Achleitner’s view. “Deutsche Bank is a vital institution for Germany and the eurozone,” he says. “If you don’t have a capital markets institution in your home region, you’re going to have a problem.”

Of all the executives interviewed for this article, Christian Sewing — a German who joined Deutsche as an apprentice nearly 28 years ago and now heads its retail and small enterprise commercial bank — was perhaps the most upbeat. “In commercial banking, we’ve taken on 4,000-5,000 new customers in the past year,” he says — as good a record as any in the past 20 years. “We lost our balance. It was good to go international. It was good to expand in investment banking. But we overdid it.”

As Deutsche ponders a successor to Cryan, some of the bank’s biggest shareholders appear keen on a big-name international outsider. But internally, a trio of Germans are being groomed as candidates. Sewing is quietly emerging as the favourite. “I think what we want to achieve is that people respect us again for being a solid German international bank with a very stable business,” he says. “We’re far away from being a bank that is loved. But look at Bayern Munich. They are not loved. But they are respected.”

If Sewing does get the job, it would be highly symbolic, restoring a German — and a Deutsche “lifer” — to the helm of Germany’s eponymous bank for the first time in more than 15 years. It should also draw a line under an expensive 20-year experiment in globalisation — and finally lay to rest the spirit of Edson Mitchell.

Follow @FTMag on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos. Sign-up for our Weekend Email here

Photographs: Hudson Hayden; Getty

Illustration by Matt Chase

Comments