UK truck driver shortage signals a broken labour market

Simply sign up to the UK employment myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

A shortage of truck drivers has led to empty shelves in British supermarkets. There is even talk of the army being called in to help. For those who wanted the UK to remain in the EU, it feels like a moment to say: “We told you so, Brexit was a disaster.” But that misses the point. The empty shelves are a visible message from a workforce that’s usually invisible. They tell a story about what’s gone wrong in this corner of the 21st-century economy — and not just in the UK.

Earlier this year Dominic Harris, who had been a truck driver since 2012, started to feel dizzy and unwell. He went to hospital, where a nurse told him his problem was exhaustion. There are legal limits on driving hours: heavy goods vehicle drivers can usually only drive for nine hours a day (currently 10 because of the shortage).

But that doesn’t mean the shifts are nine hours long. It was typical for Harris, who is 39, to be out of the house for 12 to 15 hours a day. When he got home, he was so tired he would go straight to bed. “I’ve lost quite a few relationships with friends,” he says. “I’ve not been the same old Dom.”

Hours can also be unpredictable. A current job advert from XPO states: “You’ll be working a minimum of 45 hours per week on an ‘any five from seven-day’ shift pattern, so your working days may change each week and could include weekend working. You will also be starting early AM and must be prepared to work through the night.”

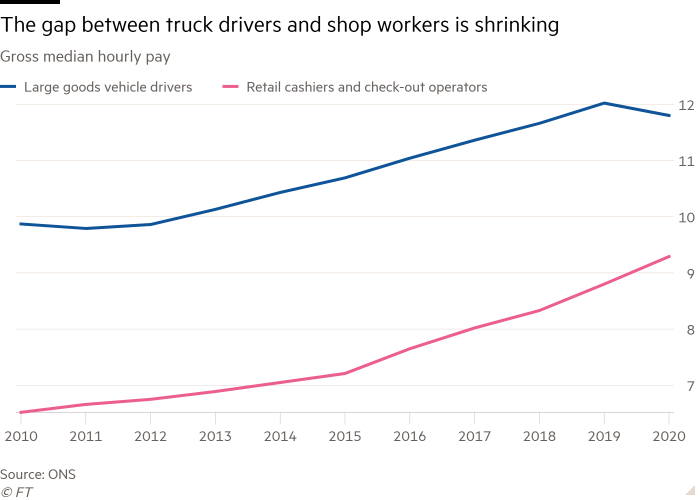

In spite of the tough hours and the fact they often pay for their own qualifications (Harris paid £1,500), drivers have been slipping down the wage ladder. In 2010, the median HGV driver in the UK earned 51 per cent more per hour than the median supermarket cashier. By 2020, the premium was only 27 per cent. They have faced a particular pay squeeze in the past five years: median hourly pay for truck drivers has risen 10 per cent since 2015 to £11.80, compared with 16 per cent for all UK employees. “Why would I want to be a truck driver, with all the responsibility, the long, unpredictable hours, if I can go to Aldi and earn £11.30 an hour stacking shelves?” says Tomasz Oryński, a truck driver and journalist based in Scotland, who is planning to move to Finland.

Kieran Smith, chief executive of Driver Require, a recruitment agency, says employers have pushed labour costs down to compete for powerful customers such as supermarkets. “Customers have enormous purchasing leverage [and] they have nailed down the haulage companies to the tiniest margins.” He says lots of drivers leave in their 30s because the hours make it almost impossible to participate in bringing up children, yet the wage isn’t high enough to support the other partner staying at home.

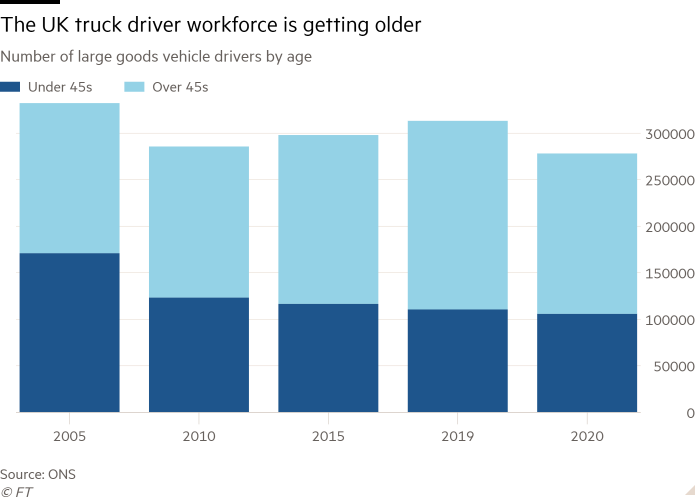

As a result, the workforce is ageing. In 2000, there was an even split between over-45s and under-45s. Now the over-45s account for 62 per cent. Between 20,000 and 40,000 people pass their tests to become truck drivers in a non-pandemic year, but many appear to leave the sector. Harris left this summer to start a business tending graves. It’s peaceful and he likes the connections he makes. He doesn’t want to go back.

Ageing workforces and labour shortages are problems in other countries too. In Europe, some eastern European companies are sending drivers to work in western countries on eastern rates of pay.

In the UK, the extent of the problem was masked before Brexit by a supply of EU drivers who helped to fill vacancies. In addition, a loophole in the UK’s badly-regulated labour market allowed drivers to set up as limited companies. This upped their take-home pay by cutting their tax (at the cost of their workers’ rights). This year the government closed the loophole, which prompted some drivers to leave. Meanwhile, Covid led to cancelled tests for new drivers and prompted many Europeans to go home.

Adrian Jones of the union Unite says the short supply means drivers now have a moment of leverage. He wants to see long-term reforms such as in the Netherlands, where a collective agreement is negotiated between employer and union groups which sets a floor on pay and conditions across the sector. “This collective agreement becomes law, so it gives transport suppliers the ability to say to their customers: this is law, so I can’t go cheaper than this,” says Edwin Atema from Dutch union FNV.

But some employers still seem intent on short-term fixes. Tesco is offering new drivers a £1,000 bonus and a “market supplement” over a six-month period. “All temporary incentives are at Tesco’s discretion and subject to review, variation and removal,” the job advert warns.

The story of Britain’s empty shelves, like that of its unpicked strawberries and unprocessed chickens, is the story of how migration combined with a weakly regulated labour market and hugely powerful retailers have allowed some goods and services to become unsustainably cheap. The system shaved money off our shopping bills but it wasn’t resilient. Remain voters are right to say Brexit helped to cause the current crisis, but wrong to say everything was fine without it. Brexit voters are right to say migration helped suppress driver pay, but as the Netherlands shows, Brexit wasn’t the only way to resolve it.

The labour shortages are a moment of reckoning. If we just use them to bicker about Brexit, we’ll drown out the real lessons in the noise.

Letter in response to this column:

Paying workers more will resolve labour shortages / From Frances O’Grady General Secretary, Trades Union Congress, London WC1, UK

Comments