Stephen Friedman — from YBAs to Mayfair establishment

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Stephen Friedman enjoys recalling how setting up his gallery in the heart of Mayfair in 1995 rattled some cages in the art world. The launch show of works by Anya Gallaccio, a sought-after Young British Artist, was a blatant encroachment into the heart of the British art establishment.

The young keen Canadian dealer threw a celebratory lunch, inviting fellow gallerists to the bash. “But they were deeply suspicious of me. ‘Why did Stephen invite us to his opening, that’s so weird, we’re competition?’ they said. I see them as colleagues, and competition is a great thing. It means I have to present a better version of myself,” Friedman says.

We (socially distance) chat in his office at 25 Old Burlington Street, the original gallery space he opened a quarter of a century ago; now he runs three galleries in the same prestigious thoroughfare, having moved from outsider to something of an establishment figure himself.

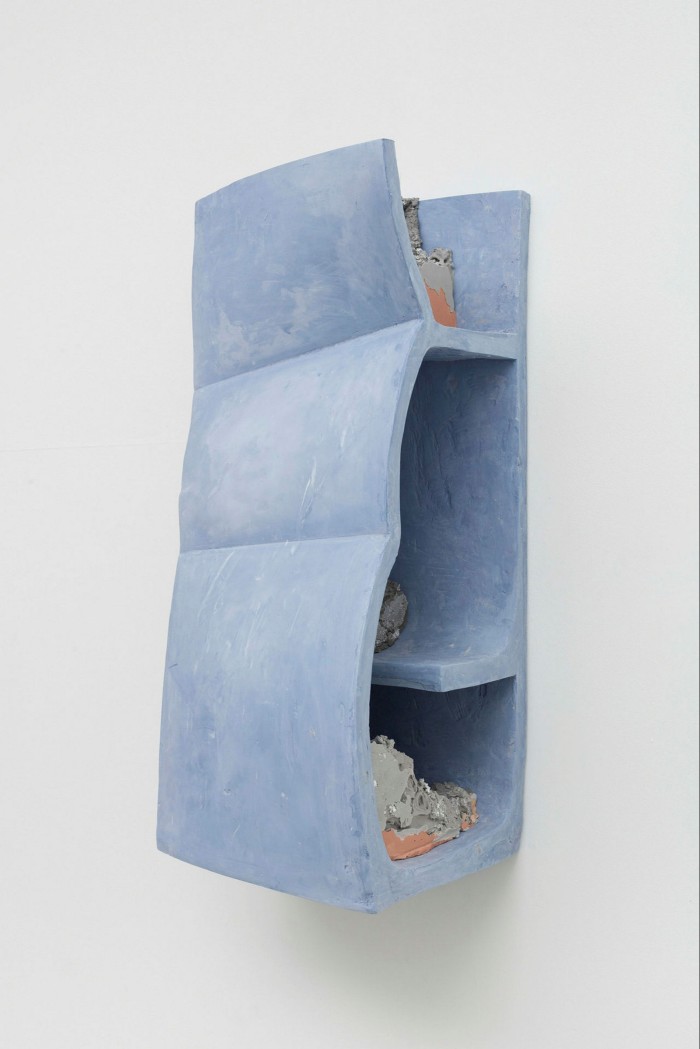

He sits on the gallery selection committee for Frieze and, in a canny, considered move, is taking over a special project space on 30 Old Burlington Street during October to show the projects he’ll display in Frieze’s online viewing rooms: 1980s large-scale paintings by Grenada-born Denzil Forrester and new works by British sculptor Holly Hendry. The presentations were intended for Frieze Masters and Frieze London respectively before Covid-19 struck, but will now double up online and in real life.

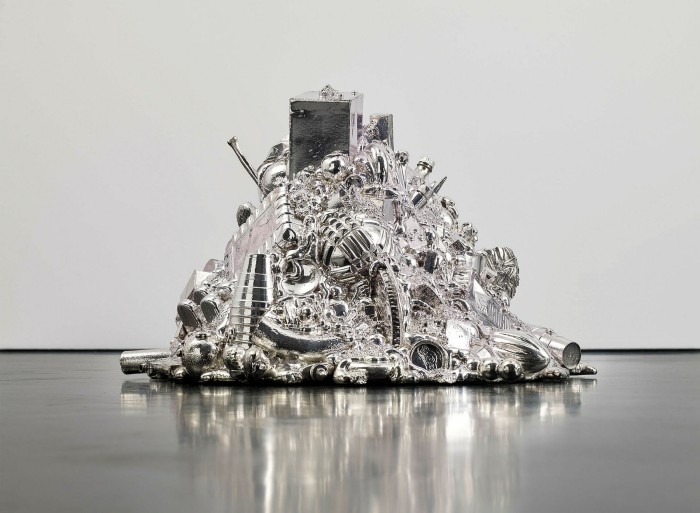

The fruits of Friedman’s labours are also on display in a special anniversary exhibition entitled 25 Years running across all his galleries. The celebratory survey includes new works made especially by his stable of artists (29 in total, including historic pieces from some estates such as that of Japanese artist Jiro Takamatsu).

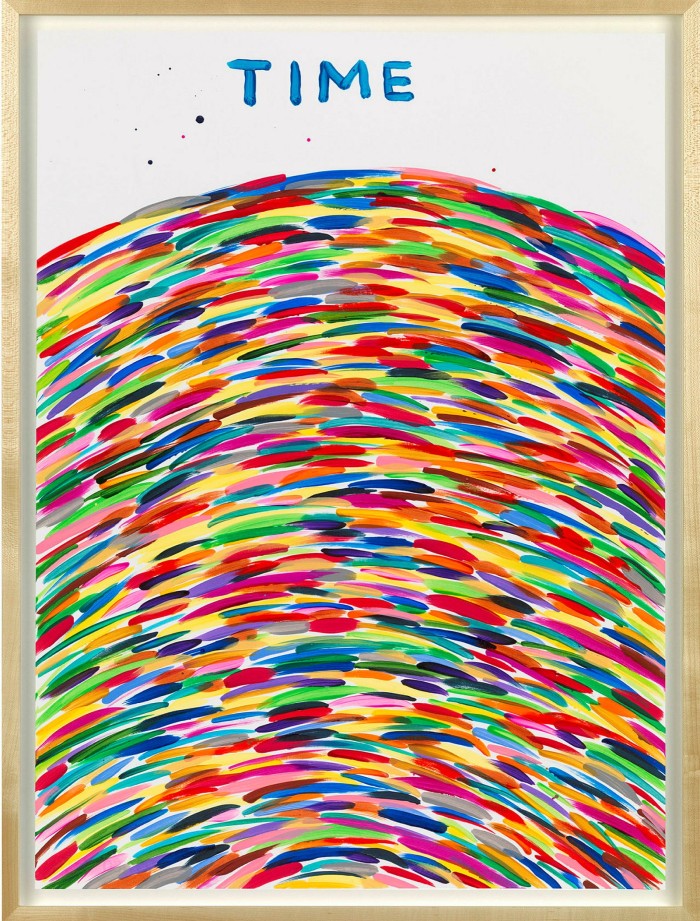

The exhibition is full of standout pieces including an impressive new painting by Forrester called Homenow (2020), which evokes a scene from the artist’s childhood (the reference to Black Lives Matter in the work is subtle but significant; look out for the BL inscribed on the shoe of the Pa Clame figure). A new burnished wood piece by the Ugandan artist Leilah Babirye makes a deep impression. Arch-japester David Shrigley has made 125 unique paintings emblazoned with the word “time”, which are as life-affirming as expected.

Born in Montreal, Friedman grew up the middle child in a “very loving” family, learning life lessons from his mother who ran an antiques business (he began collecting aged 13, buying three landscapes by artists from the Canadian “Group of Seven” collective). In his mid-twenties he left Canada for London, enrolling on a Masters programme at Sotheby’s in 1989. With his love for tradition, Britain was the perfect fit, he says.

His adoration of the UK — “I have immense respect for the Queen” — takes me aback. The fabled British resolve, stiff upper lip and sense of humour inspire him. But Friedman also acknowledges the parlous state of the nation. “I’m very much anti-Brexit. But I’d rather be in a situation where we’re moving in one direction finally than being in a situation of not knowing, which is much more uncomfortable,” he says.

Friedman is an intriguing art world player who has flickered across my radar for more than two decades (prior to our discussion, we’d only chatted briefly once at a Shanghai art fair). “He’s been key to the London scene but kept a surprisingly low profile,” one dealer tells me. Friedman himself often reminds me that he’s a very private person. On the flip side, “When I want to be, I’m a total social animal,” he says.

We unpick his business strategies over the years. When he launched the dealership, the UK economy was still floundering in the wake of the far-reaching 1992 recession. “The rent was £18,000 a year in 1995; at the time I thought, how I am going to be able to afford to pay that? My projections showed I wouldn’t make money for three years, I started making money after a year,” he says.

He realised from the outset that he could not rely on the homegrown sector as the local (British) collector base was still relatively conservative. “This was a nation weaned on traditional art for years. I knew right away that I was going to sell to international collectors. I had to be in Mayfair because I knew they'd come and either stay in Claridge's or Brown’s,” Friedman says.

How have things changed on the business front? The risks he takes today are more calculated than they were 25 years ago, he says. “I have bigger financial responsibilities. So I do think a little more strategically when I take on artists, how they fit into the programme, how they might be perceived in the market, how and if we can build their markets,” he adds.

His husband Edward, a finance expert, has become involved in the business. “We love working together,” says Friedman. “He’s much more charming than I am.”

He reiterates how comfortable he is in his own skin but is just as laudatory about other people, citing influential figures such as his mother and the legendary late New York dealer Leo Castelli. The pair met in 1994 in Minneapolis and instantly hit it off. “I just thought he was elegant, erudite had an amazing eye and seemed to be ahead of the curve. He also had amazing artists in his programme.”

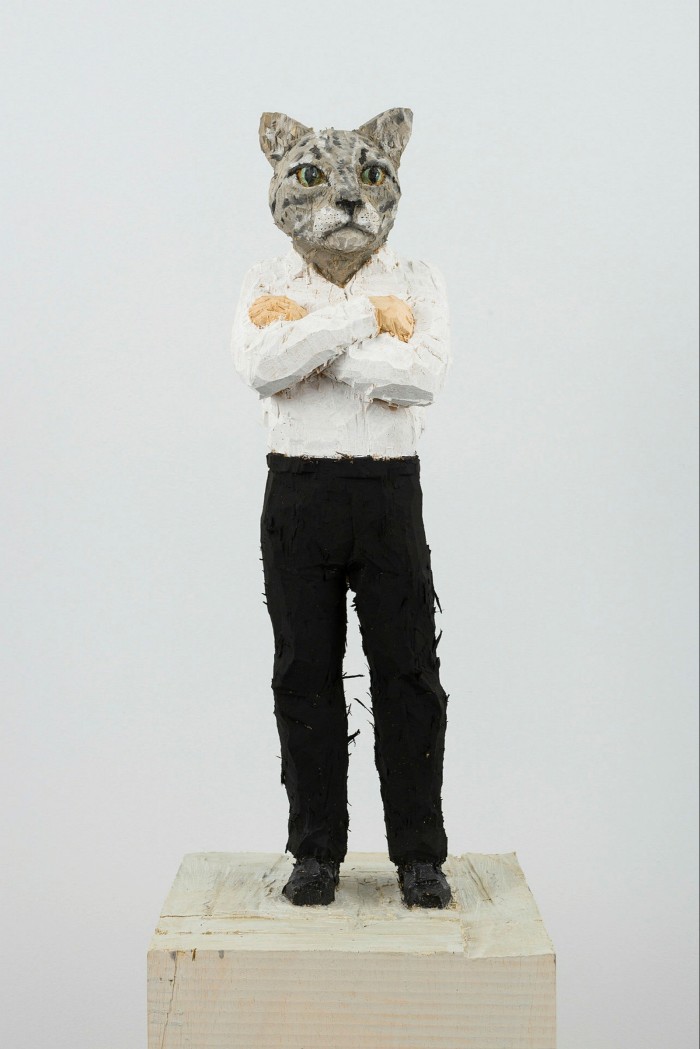

I turn to artists in Friedman’s stable for feedback (those with the gallery from the outset include Stephan Balkenhol, who joined in 1995; Tom Friedman signed up in 1996 along with Shrigley). South African artist Kendell Geers tells me that “Stephen Friedman Gallery feels more like a family than a gallery that places artists at the centre of the most generous table. In the years since my first solo show there in 1999 . . . the team has made sure that no idea is ever wasted.”

Friedman’s championing of under-represented names, including several Latin Americans such as the Brazilian artist Luiz Zerbini, marks him out. Babirye, fleeing from persecution in Uganda, is a recent key signing along with Hendry and Marina Adams. “I don’t necessarily look for the unchampioned artist although I seem to somehow naturally gravitate towards a number of them. Marina Adams is in her early sixties, she’s never shown in Europe before. I’ve always loved her work.” He adds, with characteristic candour: “There are a lot of really good artists out there — there is also a tremendous amount of rubbish — for me there’s nothing in between.”

Recently taking on Forrester, who moved to London from Grenada in 1967, was also a masterstroke. “The first time I saw the work I was knocked for six. He had never had a gallery . . . We then went to see him in Cornwall [in his studio], I knew everybody would really love the work. I have to say I focused first on the American market, and had a great immediate reaction.” Price points for Forrester’s works currently range from £100,000 to £400,000. “When you price your works, you inherit a pricing structure, you have to use your instincts, you have to know the market,” Friedman says.

What happens next? “We’re doing better than we initially anticipated but this is going to be a two-year interruption to my business at least,” he says, adding that the gallery could not have survived the pandemic without its growing digital platforms. “Trying to engage clients virtually was challenging initially but it had its big pluses too because everybody was homebound and happy to talk,” he says. Between March and July he was glued to Zoom after inviting his “top 100 most active clients” for an online catch-up (almost all of them accepted).

One client, Dallas-based collector Howard Rachofsky, says the “process of collecting can be arduous but with Stephen it’s very reasonable and thoughtful.” The pair bonded over Bendicks Bittermints confectionery. “He introduced us to these addictive mints,” says Rachofsky.

Finally, would he do it all again? “In a heartbeat,” Friedman says, before I even finish asking the question.

‘Denzil Forrester in Rome’ and ‘Holly Hendry: Busy Bodies’, both October 5-31; ‘25 years’, to November 7, stephenfriedman.com

Comments